The way in which evolutionary explanations can be so readily applied to apparent differences in human psychology does highlight the glaring gap in the liberal consensus: if natural selection has produced the obvious physical differences in different human groups, could it not have done the same with cognition and behavior?

Cognitive scientist Steven Pinker has provided a measured critique of the Jewish IQ hypothesis—the claim that the higher IQ of Ashkenazi Jews is more genetics than culture. “The standard response to claims of genetic differences,” he has written, “has been to deny the existence of intelligence, to deny the existence of races and other genetic groupings, and to subject proponents to vilification, censorship, and at times physical intimidation”.

Harvard geneticist David Reich argued in an oft-cited 2018 New York Times Magazine essay, the consensus response can be wrong-headed, short-sighted and counter-productive. Beginning in the early 1970s, based in part on ground-breaking research by geneticist Richard Lewontin, a consensus emerged that “there are no differences large enough to support the concept of ‘biological races.’” As Lewontin had contended, to the extent that there was variation among humans, most of it was because of “differences between individuals.” This was the accepted interpretation, canonized if you will by Jonathan Marks in 1995.

But Reich argued that this ‘simple logic’ defies science and common sense:

…this consensus has morphed, seemingly without questioning, into an orthodoxy. The orthodoxy maintains that the average genetic differences among people grouped according to today’s racial terms are so trivial when it comes to any meaningful biological traits that those differences can be ignored.

The orthodoxy goes further, holding that we should be anxious about any research into genetic differences among populations. The concern is that such research, no matter how well-intentioned, is located on a slippery slope that leads to the kinds of pseudoscientific arguments about biological difference that were used in the past to try to justify the slave trade, the eugenics movement and the Nazis’ murder of six million Jews.

I have deep sympathy for the concern that genetic discoveries could be misused to justify racism. But as a geneticist I also know that it is simply no longer possible to ignore average genetic differences among “races.”

Reich and other geneticists and social scientists have come to believe that creating and policing taboos on touchy topics vacates the high ground to racists and bigots. Otherwise vacuous ideas acquire a veneer of credibility when presented as hidden knowledge that the public is not meant to know. This tendency to deny and denounce, however well-intentioned, may also stymy research that brings practical benefit to the very marginalized or oppressed groups that progressives profess to champion.

The more we know about human behavioral traits, the better able we are to address their potential negative consequences. How we act is mediated through innumerable other genetic and environmental influences; for example, in affluent social environments risk-taking may be advantageous (think individual dynamism or entrepreneurialism); in economically-deprived situations, however, this same trait may instead result in drug and alcohol abuse, criminality or violence. Again, such conclusions do not contradict the progressive imperative to improve social environment to mitigate undesirable social outcomes.

The original basis for Cochran’s and Harpending’s evolutionary hypothesis was genetic research into debilitating brain disorders predominantly found in Ashkenazim. Cochran and Harpending then speculated that these disorders might be an indication of rapid, recent genetic change in response to new environmental conditions—what they called ‘positive selection’. Genes that cause diseases are usually phased out of the human genome, as its carriers die without passing on the killer mutation to future generations. But some negative mutations survive. Why?

Consider sickle cell disease. In the sickle cell case, an increased prevalence of malaria due to new agricultural practices is thought to have sparked a partially successful genetic response, with two copies of the sickle cell gene providing malarial resistance but a single copy causing anaemia. In other words, sickle cell disease has not disappeared because the mutation also confers, in some populations, a survival benefit.

According to Cochran and Harpending, similar trade-offs may have occurred in the Ashkenazim case, with the deleterious brain disorders the unfortunate consequence of genes that, in different combinations, enhance rather than impair cognitive function. Their speculation about Jewish employment in Medieval Christian Europe, therefore, was Cochran’s and Harpending’s attempt to describe a possible recent selective pressure on cognitive function—one that, they believed, neatly explained both the incidence of specific cognitive disorders and the perceived greater intelligence of a distinct ‘racial’ group, Ashkenazi Jews.

Facts before ideology

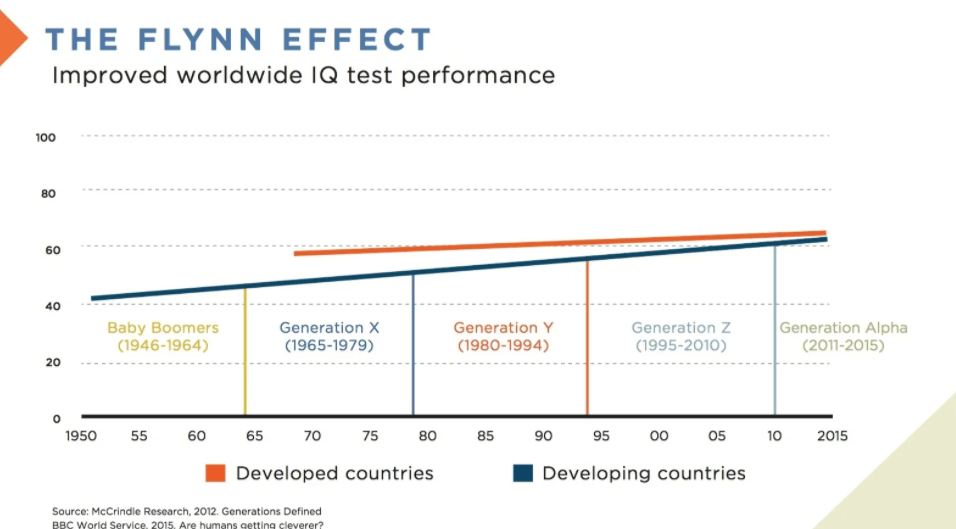

The work of political scientist James Flynn, who died in 2020, exemplifies how a commitment to scientific veracity on ‘taboo’ topics does not diminish liberal ideals. A lifelong social democrat, Flynn did not shy away from openly investigating recorded racial differences in IQ—how else, he reasoned, would we ever come to understand the determinants of intelligence and use this knowledge for social good? Yet if academic censorship had prevented his studies, Flynn may never have discovered some of the strongest evidence of environmental (rather than genetic) influences on intelligence—the so-called “Flynn effect” of rising intergenerational IQ. This effect, while still debated and not fully understood, clearly demonstrates the strong environmental (i.e., social and cultural) influences on human cognitive abilities.

Politically, the Flynn effect sustains one long-held leftist belief while discrediting another. For a start, this evidence of culturally-induced cognitive change backs up progressive demands to improve the social and educational environment of those failed by the existing system. It also indicates that the current low attainment of some groups relative to others—that emphasized by the likes of Rushton and seized upon so gleefully by racists—is not ineluctable or inevitable. Importantly, evidence such as the Flynn effect clearly show that genes are not destiny.

It is not and never has been either nature or nurture, genes or environment. Genetically-mediated behaviors (such as risk-taking) have different outcomes in different social environments, while different social environments bring about different genetically-mediated behaviors (such as those associated with the Flynn effect’s rising IQ). Even the act of learning to read causes changes in how the human brain processes and perceives the world.

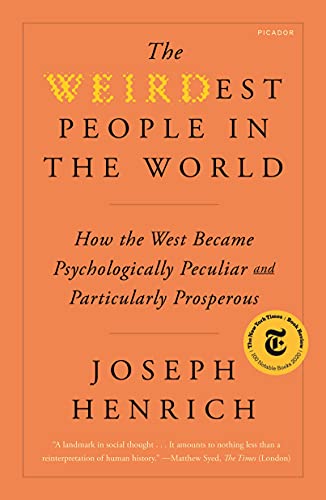

As outlined in anthropologist Joseph Henrich’s The WEIRDest People in the World, cultural processes appear to have changed the way WEIRD (Western educated industrialized democratic) people see the world. For example, Henrich argues that specific cultural changes in Medieval Europe—the Catholic Church’s suppression of marriage to close relatives, say, or the Protestant emphasis on individual literacy—have recently and rapidly (in evolutionary terms) transformed WEIRD people’s cognitive behavior. For Henrich, this is a process of nature via nurture, in which culture changes behavior, which then feeds back into culture—what Jon Entine in Taboo called a “biocultural feedback loop”: nurture determines nature as much as genes determine environment.

As outlined in anthropologist Joseph Henrich’s The WEIRDest People in the World, cultural processes appear to have changed the way WEIRD (Western educated industrialized democratic) people see the world. For example, Henrich argues that specific cultural changes in Medieval Europe—the Catholic Church’s suppression of marriage to close relatives, say, or the Protestant emphasis on individual literacy—have recently and rapidly (in evolutionary terms) transformed WEIRD people’s cognitive behavior. For Henrich, this is a process of nature via nurture, in which culture changes behavior, which then feeds back into culture—what Jon Entine in Taboo called a “biocultural feedback loop”: nurture determines nature as much as genes determine environment.

What does this mean for the liberal “standard response” to the question of evolved human biodiversity?

In short, Darwinian reasoning can help explain why the world is as it is, but it doesn’t tell us how it could or should be. At the same time, the more we understand about how both genes and culture make us what we are, the more knowledge we will have to change society in desirable ways. None of this conflicts with liberal political aspirations. To rephrase a famous ‘progressive’ slogan: evolutionists can interpret the world in various ways; it is still up to us to change it.

Or to paraphrase James Flynn, who remained sanguine about the possibility of deeper genetic influences on intelligence, if everybody had a decent standard of living, fewer people would worry that there were more accountants or dentists of one race than another.

Disease proclivity, like sports ability and IQ, are the product of many genes with environmental triggers influencing the “expression” of our base DNA. It’s further shaped throughout our lives by a ‘biosocial feedback loop’.

Why touch this third rail of human biodiversity? After all, as UCLA’s Jared Diamond has noted, “Even today, few scientists dare to study racial origins, lest they be branded racists just for being interested in the subject.”

Acknowledging the fact of evolved diversity—in our bodies and in our brains—isn’t racist. It will not perpetuate existing racial inequalities. Indeed, what will maintain the current status quo, and encourage the rants of the alt-right, is wilful denial of the complex environmental and genetic factors that underpin human physical well-being and social behavior.

Over the past two decades, human genome research has moved from a study of human similarities to a focus on population-based differences. We readily accept that evolution has turned out Jews with a genetic predisposition to Tay-Sachs, Southeast Asians with a higher proclivity for beta-thalassemia and Africans who are susceptible to colorectal cancer and sickle cell disease. So why do we find it racist to suggest that Usain Bolt, in addition to incredible training commitment, can also thank his West African ancestry for the most critical part of his success—his biological make-up?

Genes influence human social outcomes; we have a moral responsibility to accept this and to use that knowledge to improve people’s and peoples’ lives.

Jon Entine is the founding executive director of the Genetic Literacy Project, and winner of 19 major journalism awards. He has written extensively in the popular and academic press on agricultural and population genetics. You can follow him on X @JonEntine

Patrick Whittle has a PhD in philosophy and is a freelance writer with a particular interest in the social and political implications of modern biological science. Follow him on his website patrickmichaelwhittle.com or on X @WhittlePM