The differences between sexes, which preoccupy so much of our cultural capital (see: tired old “battle of the sexes” sitcom humor, the importance of Laverne Cox), did not always exist. Nor did multicellular life. How sexes and sexual reproduction arose and how they came to dominate life as we know it today is one of the Big Questions of biology.

Now, thanks to some gender-bending transgenic research with algae, a small team of scientists has hard evidence that there might be a genetic “master switch” that began the path toward sexual differentiation with visibly indistinguishable “plus” and “minus” forms of algae and later developed in complexity to regulate the development of big, sedentary eggs and small, motile sperm.

The researchers used the Volvox genus of algae, which contains within its lineage a microcosm of sex-difference evolution. Carrie Arnold at National Geographic reports:

Volvox […] contains a wide variety of algae, from simple unicellular organisms to large, complex multicellular life. V. carteri lives in colonies of 2,000 cells, whereas another species from a different family, such as Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, have simple colonies of only four cells. Their diversity in size is also matched by a diversity in reproductive methods.

“It’s almost as if these algae were tailor-made to help us understand important evolutionary transitions,” Washington University biologist and lead author James Umen told Arnold.

Umen and his team focused on two species: Volvox carteri and Chlamydomonoas reinhardtii. Of the two, V. carteri has distinguishable sex cells (sperm and eggs), whereas C. reinhardtii has a more primitive arrangement of “plus” and “minus” sex cells which are indistinguishable upon external inspection but nonetheless must pair up +/- in order to reproduce.

Tia Ghose at Live Science explains further:

The team focused on a single gene, dubbed MID, which is present in the “plus” mating type of the single-celled C. reinhardtii but absent in the “minus” mating type. In the multicellular V. carteri, males have their own version of the MID gene, whereas females don’t.

The two versions of the MID gene were very similar in both species. Based on the differences in the gene sequence (or the sequence of letters that makes up the gene), the team concluded that the MID gene in V. carteri evolved from the one in C.reinhardtii.

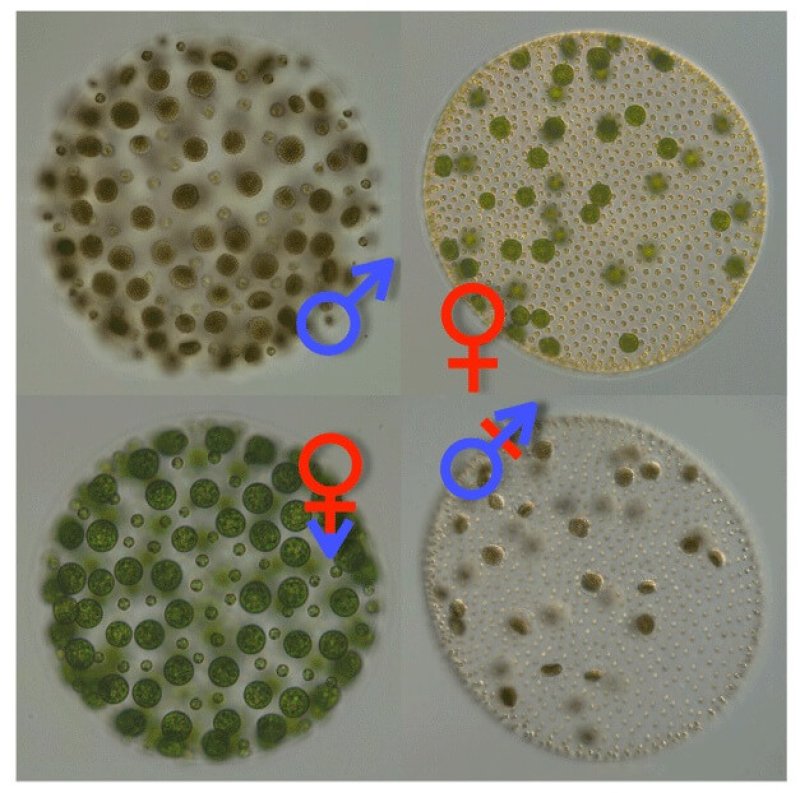

Next, the team inserted the MID gene into female V. carteri organisms.With that one insertion, the females’ eggs turned into sperm packets. Meanwhile, reducing the expression of the gene in males turned their sperm packets into eggs.

“By manipulating this one gene we can essentially give Volvox a sex change,” Umen said.

“Much to our surprise, one single gene had evolved the capacity to affect the male/female difference,” Umen also told Arnold. The sex-swapped transgenic algae were even able to produce viable offspring (though not without quirks) with their unmodified counterparts.

Umen and his team were rather expecting to find evidence that the two instances of sexual differentiation — one more primitive, one a bit closer to what we generally think of when someone says “sex cells” — had arisen due to mutation in separate evolutionary instances. They were not expecting to find evidence that the gene that made “plus” and “minus” in C. reinhardtii would be implicated directly in the more complex formation of eggs and sperm in V. carteri.

From the paper proper, published this week in PLoS Biology:

Although it was reasonable to predict that the route for evolving sexual dimorphism would be through addition of new genetic functions and pathways […] we found instead that a single conserved [gene], MID, is largely responsible for controlling male versus female sexual differentiation.”

In brief: MID seems to be a ‘master switch’ gene that is implicated in sexual difference across the complicated and evolutionarily diverse Volvox genus lineage. The evolutionary pattern discovered by Umen and his colleagues may represent, in the words of Science 2.0, a “blueprint” for how sexual difference arose in other evolutionary lineages.

It might help us understand a bit better how life made the mind-boggling trip from indistinguishable “plus” mating-types in algae to the unmissable purple plumage of the male peacock.

Kenrick Vezina is Gene-ius Editor for the Genetic Literacy Project and a freelance science writer, educator, and naturalist based in the Greater Boston area.

Additional Resources:

- “How did sex start?” Meredith Knight | Genetic Literacy Project

- “What your science teacher told you about sex chromosomes is wrong,” Susannah Locke | Vox

- “Genetics Of Sex — Beyond Just Birds And Bees,” Genetics Society of America