Editor’s Note: This is the third article in a three-part series exploring some common concerns heard about GMOs. Part one examines genetic engineering versus traditional breeding. Part two looks at herbicide use.

There is some odd and fuzzy-headed thinking that asserts that crop breeding should be exempt from intellectual property protection. Often expressed as “Nobody should be able patent life”. There is a certain emotional appeal that makes sense there, and maybe a moral intuition that could be expanded on coherently. I think if people want to hold those views, that’s fine, but they should understand their history and the economics of plant breeding a little better.

It’s a bit curious that people think that plant breeders should not have the same protections as other inventors and innovators. In support of the Plant Patent Act of 1930, Thomas Edison testified before Congress in support of the legislation and said that “This [bill] will, I feel sure, give us many Burbanks.” referring to Luther Burbank the great plant breeder of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

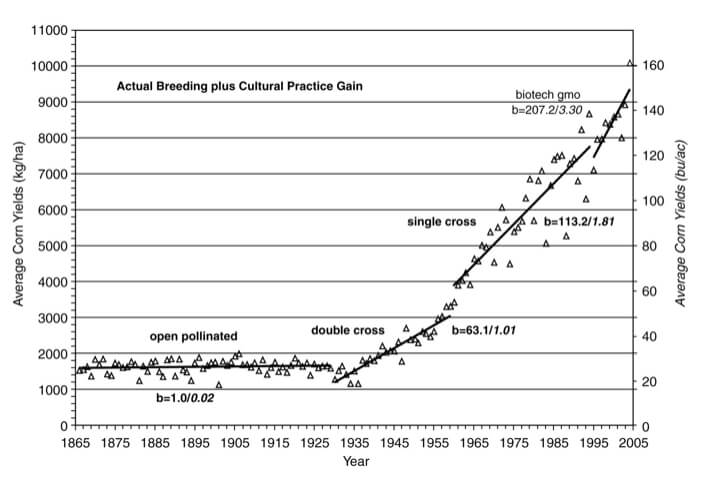

The Plant Patent Act of 1930 didn’t cover sexually propagated plants, so corn wasn’t covered until the Plant Variety Protection Act of 1970. However, it was also around 1930 that hybrid breeding became the norm for corn. This meant that farmers had a reason to buy new seed every year and breeders could make money by giving them something better every year. Hybrids work by cross breeding two “inbred” varieties with complementary traits. On top of combining useful traits, the first generation of this crossing exhibits what’s called hybrid vigor– the children don’t just combine the positive traits of the parents, they are more robust as well. Thus, in crops where hybrid breeding works, they took the world by storm.

The downside is that hybrids don’t breed true. Farmers saving the seed harvested from these hybrids would not get a consistent crop from the saved seed. Dominant and recessive genes would play out in various ways from one seed to the next. Plants might not all grow to the same height or reach harvest maturity at the same time, creating headaches for farmers that were more easily dealt with by leaving seeds to the seed companies.

Likewise even for crops like soybeans that aren’t hybridized. Farmers might save seeds for a few years, but breeders continue to improve soybeans every year and the seed becomes “tired” after a few years of inbeeding. After a few years, “saved seed” yields will be less than when the seed was newly purchased even as yields for the seed on the market continue to rise.

Corn yields have increased by a factor of six since breeders had a real incentive to create better seeds. That’s the economic incentive for breeders. Farmers, by and large, don’t begrudge seed dealers from making money on providing a great product.

Going back to the seeds and yields that we had before 1930 would be an economic and ecologic disaster. Just like with software, there is room for open source projects for in plant breeding. And there are interesting projects on that front. We also need to restore public funding for breeding programs. But as with any capital intensive innovation, patents are valuable to make sure that innovation keeps moving forward in ways disciplined by the market.

What about those lawsuits?

As far as Monsanto suing farmers for cross pollination goes, this verges on urban legend. It hinges on a misunderstanding of the facts on the ground when it comes to a few high profile lawsuits. It’s true that Monsanto has filed suit against farmers who violated the terms of the technology agreement covering the sale and use of their biotech seeds, but they haven’t been against farmers who were the innocent victims of accidental pollination.

First, understand that the technology agreement covering biotech traited seeds is similar in it’s logic to the End User’s License Agreement you consent to when you buy software. It costs money to develop software, but once it’s made, it’s easy to reproduce – you just make a new digital copy at no cost, so software companies require users to sign off on a legally binding agreement not to make copies of the software they buy. The same goes for farmers.

Farmer’s are not generally uncomfortable with the terms of the seed agreements that they sign with the seed companies. Don’t believe me? You shouldn’t. But you should take some time and read Indiana corn and soy farmer Brian Scott going over his agreement point by point before you keep spreading the idea that farmers are enslaved by these agreements. Or Iowa farmer Dave Walton. Or go into the Food and Farm Discussion Lab forum and ask farmers, they will be happy to talk about it.

Let’s talk about the lawsuits.

If you believe that Monsanto is evil because it sues innocent farmers you probably ended up there because of the stories of Moe Parr, Percy Schmeiser and/or Vernon Bowman. Those are the big headline stories in various documentaries. Let’s go through them each in turn.

Percy Schmeiser knew damn well he was trying to pull a fast one when he saved Roundup Ready canola to replant. Schmeiser grew canola in Saskatchewan, Canada. He claims that when he sprayed his fields with RoundUp, some canola plants survived. This suggested to him that they had been cross-pollinated from a neighbor’s field and were now RoundUp Ready. So he saved the seed for reuse. Meaning, he thought he had found a loophole to obtain a free version of the premium seed his neighbor had purchased. When Monsanto approached him about paying his technology fee for the right to use their weed control system, he claimed that he was exempt because he found the seeds on his farm, making them his property. The Canadian Supreme Court 5-4 ruling found in favor of Monsanto because the company owned a valid patent and Schmeiser violated the patent by intentionally replanting the Roundup Ready seed that he had saved.

Whether you agree with the court’s finding or not, whether you buy Schmeiser’s account of the events or not; what’s clear is that Schmeiser was not sued for accidental pollination. He was sued because he wanted to intentionally use RoundUp Ready crops for free. As a glyphosate spraying, GMO stealing farmer became an unlikely hero of an organic movement that isn’t particularly concerned with the facts, as long as they can make Monsanto the bad guy.

Moe Parr was a seed cleaner who intentionally deceived his customers into believing that it was OK for them to save RR soybeans in violation of their agreements with the company. [PDF] Read the injunction against him, it’s easily read in a few minutes, and it clearly shows that he’s no hero. The court found him guilty of misleading his customers. Note that none of his customers were sued for mistakenly saving seeds in good faith.

The last headline case was Vernon Bowman. He bought soybeans from an elevator that could legally sell soybeans for feed but not for planting. Bowman purchased seeds legal for use as animal feed and planted them for a late season second planting, thinking he had found a loophole, he started saving the RR seeds. He had been using RR seeds under an agreement for his first planting so he knew damn well what how the patent agreement worked. Again, he wasn’t sued for accidental cross pollination. He was sued because he wanted biotech seeds and he didn’t want to pay the prices that his neighbors were paying.

The last headline case was Vernon Bowman. He bought soybeans from an elevator that could legally sell soybeans for feed but not for planting. Bowman purchased seeds legal for use as animal feed and planted them for a late season second planting, thinking he had found a loophole, he started saving the RR seeds. He had been using RR seeds under an agreement for his first planting so he knew damn well what how the patent agreement worked. Again, he wasn’t sued for accidental cross pollination. He was sued because he wanted biotech seeds and he didn’t want to pay the prices that his neighbors were paying.

Just to put a final cork in this bottle of anti-GMO KoolAid, a few years ago the Organic Seed Growers and Trade Association (OSGATA) and a group of dozens of organic and conventional family farmers, seed companies and public advocacy interests sued Monsanto in an attempt to proactively prevent the company from suing farmers in cases of accidental pollination. The court threw the case out before going to trial because plaintiffs had failed to provide any instances of farmers being sued for accidental pollination, so there was no controversy to provide a basis for even hearing the case.

Despite the fact that OSGATA couldn’t come up with any examples of farmers being sued for accidental pollination, this is an objection you can see people making to biotech crops on any given day.

A section of this article previously appeared on Food and Farm Discussion Lab under the title “3 Most Common Internet Objections to GMOs” and has been republished with permission from the author. Marc Brazeau is a writer on food and agriculture. He blogs at Food and Farm Discussion Lab. Follow Marc on Twitter @realfoodorg.