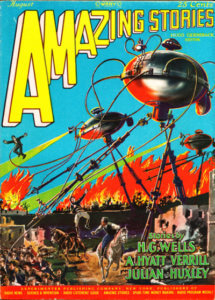

In the sci-fi classic The War of the Worlds, Martians attacking the Earth drop from the sky, dying, victims of bacterial infections to which humans have become immune. H.G. Wells wrote the novel from 1895 to 1897, set in Victorian England.

Then on October 30, 1938, a radio version aired in the US, with Orson Welles narrating so convincingly that many listeners panicked, thinking that Martians were truly invading. The first of five film adaptations debuted in 1953, set in California.

Then on October 30, 1938, a radio version aired in the US, with Orson Welles narrating so convincingly that many listeners panicked, thinking that Martians were truly invading. The first of five film adaptations debuted in 1953, set in California.

The 2005 film has Tom Cruise running around as Dakota Fanning screams her head off, this time in New Jersey. The closing lines summarize the microbiology of the situation:

“From the moment the invaders arrived, breathed our air, ate and drank, they were doomed. They were undone, destroyed, after all of man’s weapons and devices had failed, by the tiniest creatures that God in his wisdom put upon this earth. By the toll of a billion deaths, man had earned his immunity, his right to survive among this planet’s infinite organisms. And that right is ours against all challenges. For neither do men live nor die in vain.”

I’m assuming that quote echoes the original, given the sexist language.

Microbes are us

Humans have not only adapted to the many microbial species with which we share the planet, but some are essential to our survival. Our microscopic bodily residents form the microbiota, their genomes our microbiome. While we’re still learning about this otherness within and on us, already a new field of medicine has arisen to manipulate or restore the microbiome. Most familiar is the fecal transplant (see 15 Facts About Fecal Transplants: The Straight Poop).

The communities of bacteria, viruses, fungi, archaea and more complex singled-celled organisms that occupy our bodies are shifting, plunging in diversity in lockstep to industrialization. And that is hazardous to our health, according to Maria G. Dominguez Bello, from the department of biochemistry and microbiology and of anthropology at Rutgers University and colleagues. They argue in the Science article that “dramatic increases in metabolic, immune, and cognitive diseases” – diabetes, asthma, obesity, allergies, autism, inflammatory bowel disease – parallel striking decreases in microbiota diversity.

But the distribution of microbiota ups and downs isn’t geographically equal. For example, the diversity of gut bacteria in South American Amerindians is double that of US human intestinal residents.

Disruption is dangerous

The microbes passed along at birth play crucial roles in establishing such physiological functions as immunity, digestion and nutrition, hormonal activity and neural transmission. The nooks and crannies of the human body harbor distinct variations on the microbiome theme, such as the armpit, penis, vagina, mouth and nostrils.

Everyday activities that are part of what we consider civilization actually derail the functions of our microbiota, including:

- Taking probiotics and antibiotics

- Circumcising infants

- Delivering newborns surgically

- Formula feeding

- Using nasal sprays, mouthwash, toothpaste, deodorant, and soap

- Eating refined and processed foods

- Drinking chemically treated water

- Living in unnatural environments

When our natural microbial inhabitants depart, others fill the vacated niches, sometimes not to our benefit. For example, Oxalobacter formigenes are bacteria that occupy the human colon, where they normally dismantle oxalate. We can’t digest it, and accumulating oxalate causes kidney stones. Will eradication of these bacteria increase incidence of kidney stones?

Microbiome biology is complex. “This is just the beginning of our knowledge about the impacts of living in an industrialized world—we need to better understand which strains in human populations are diminishing and what the functional and pathological implications are for these losses,” write the authors of the new paper.

Changing microbiomes in response to industrialization will only accelerate, because more than half of the global human population lives in cities and that proportion is growing. According to the researchers:

We suspect that the microbes disappearing in urban societies are those that are needed to maintain health and prevent many metabolic, immune, and cognitive diseases. If microbial disruption due to urbanization increases the diseases of industrial societies, then the current global pandemics will worsen, with economic impact jeopardizing health care systems.

Taking action

Taking action

We can slow the decline in microbiota diversity: eat more whole foods, minimize use of antibiotic drugs and antimicrobial cleaning products, emphasize breastfeeding over bottlefeeding, and perform cesarean sections and circumcisions only when medically necessary. But people aren’t likely to give up deodorants and drugs and the other comforts of modern civilization to restore something essential that they can’t see.

Other efforts at slowing the loss of diversity are more directed, such as taking metabolites that “good” bacteria require, like lactate to restore the vaginal microbiome. The authors call on nutrition researchers to develop “dietary additives to replace our lost chemistry.” But the microbiome is intricate and ever-changing; adding or removing a species can have unforeseen effects.

Any active approach to maintain, restore, or alter the microbiome should consider the effect of natural selection over generations, the researchers maintain. We differ. The roster of bacteria in the intestines of a person whose ancestors came from France isn’t the same as that from someone whose ancestors lived in Patagonia, China or Ethiopia. One study found quite different gut microbial communities in healthy children and adults from Venezuela, rural Malawi and US cities. The same probiotic given to individuals from these different backgrounds and ancestry had different effects on the microbiota.

A global human microbiota vault emphasizing traditional peoples

Because it’s so hard to get people to change their habits, coupled with the challenge of altering microbiota, the authors suggest developing a microbial version of Noah’s Ark to preserve today’s diversity before it plunges further, to counter helpful species disappearing entirely or harmful ones gaining a toehold.

“We’re facing a growing global health crisis, which requires that we capture and preserve the diversity of the human microbiota while it still exists. These microbes co-evolved with humans over hundreds of millennia. They help us digest food, strengthen our immune system and protect against invading germs. Over a handful of generations, we have seen a staggering loss in microbial diversity linked with a worldwide spike in immune and other disorders,” said Dr. Dominguez-Bello in a news release.

They suggest collecting and storing microbes from the least urban parts of the planet, from “traditional peoples in developing countries,” to preserve the diversity. Several intriguing studies have compared microbiomes of people in different societies.

One investigation examined seasonal cycling in the gut microbiome from 350 stool samples of the Hadza hunter-gatherers of Tanzania, for more than a year. These people eat what they can catch, kill, or gather, finding berries and honey in the wet season and hunting for meat in dry times, supplementing throughout the year with tubers and baobab. The populations of microbial species that wax and wane with the seasons differentiate the Hadza from 18 other human populations, and the Hadza maintain a more diverse microbiota. For example, Hazda guts house a more diverse array of microbes whose enzymes digest plant-based carbs than do the innards of US residents.

In another study, researchers discovered the most diverse human microbiomes in samples from the mouths, forearm skin and feces of 34 Yanomami. These Amerindians live in the High Orinoco state of Venezuela and are one of the last peoples to have had no contact with modern societies. Surprisingly, the Yanomami microbiome includes antibiotic resistance genes, even though they and their ancestors had never been treated with antibiotics. Perhaps these genes illustrate what paleontologist and science writer Stephen Jay Gould called “exaptation” – a new function for an existing gene.

Inspiration for the Noah’s Ark of Microbes comes from the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, a storage facility “deep inside a mountain on a remote island in the Svalbard archipelago, halfway between mainland Norway and the North Pole.” The vault is the world’s largest collection of crops seeds, preserving botanical diversity so that people can replenish crops in the aftermath of natural or human-made disasters.

Preserving our microbiomes is possibly even more crucial than saving seeds. “We owe future generations the microbes that colonized our ancestors for at least 200,000 years of human evolution. We must begin before it is too late,” the team concludes.

Ricki Lewis is the GLP’s senior contributing writer focusing on gene therapy and gene editing. She has a PhD in genetics and is a genetic counselor, science writer and author of The Forever Fix: Gene Therapy and the Boy Who Saved It, the only popular book about gene therapy. BIO. Follow her at her website or Twitter @rickilewis