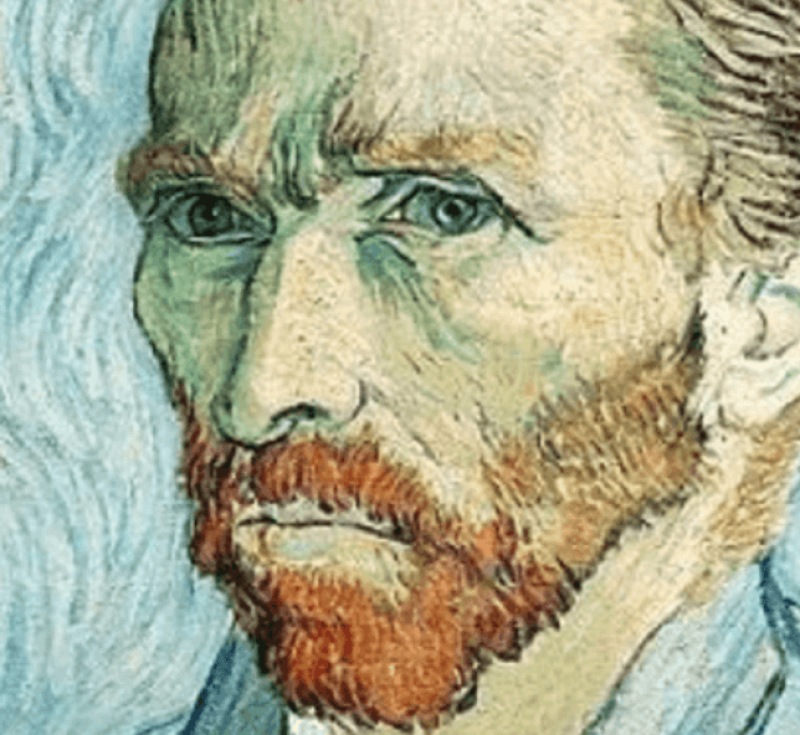

Van Gogh was by far not the only example of an apparent merger between psychiatric disorders and creativity. Composer Ludwig van Beethoven, artist Edvard Munch, poet Sylvia Plath, and novelist David Foster Wallace were all known both for an ability to produce something unprecedented and unique, and for suffering from one or more mental illnesses.

Some scientists also have suggested that illnesses like bipolar disorder or schizophrenia may rewire the brain differently enough in artists and other “creative” types so they can come up with ideas unattainable to “normal” people. However, more recent (and more carefully designed) studies are beginning to question this connection, at least on a genetic and biological level.

2015 saw two different perspectives; one from a study which claimed that such a connection existed, and another which collectively pretty much stomped on the first.

In the first study, an Icelandic research team found a positive correlation between scores that indicated higher risks of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder and “creativity.” While the study size was large (medical and genetic data from 86,000 people, and 1,000 “creative” types), the researchers measured creativity merely as being a member of a professional society of artists, dancers, musicians, writers or actors, ignoring people who were creative but “amateur.”

Another problem was that the genetic variants that created the connection only explained six percent of the cases of schizophrenia, and one percent of bipolar disorder cases. Looking at the study from the other direction, the risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder explained even fewer people with creative affiliations.

However, an earlier study found that most people in the “creative professions” were not any more likely to suffer from mental illness than members of any other professional group (with the exception of bipolar disorder, and apparently writers were more strongly associated with schizophrenia, bipolar and a host of other illnesses). And in her 2012 book, The Insanity Hoax: Exposing the Myth of the Mad Genius, psychologist and musician Judith Schlesinger pointed to significant inadequacies in diagnosing mental disorders (some of which we’ve discussed in other Genetic Literacy Project articles), particularly the arbitrariness of arriving at a specific diagnosis, as well as shortcomings in previous research that made the madness-genius connection.

Schlesinger dismissed some research, including a popular book Touched with Fire: Manic Depressive Illness and the Artistic Temperament by Kay Redfield Jamison as “pseudoscience.” Much of the research making the mad genius connection has been based on a study conducted in 1891 by Cesare Lombroso—according to Schlesinger, much of Lombroso’s data was not systematic, instead relying on anecdotes and poorly constructed comparisons.

Instead, Schlesinger pointed to creative people as “…actually complicated, not crazy; they are disciplined and committed, happy to take on hard projects and work hard at them; and they are intensely focused, with a ‘rage to master’ their chosen domain.”

So, the debate continues. Until we have better definitions of mental illnesses that are based more on genetics and biology than behavior, and even a better definition of what makes someone creative, it will be very difficult to make a solid connection between creative genius and mental health. After all, when Van Gogh removed part of his ear and suffered from a number of maladies, housemate Paul Gauguin was equally creative but at the time (he later contracted syphilis) suffered from none of these.

A version of this article previously ran on Feb. 24, 2017.

Andrew Porterfield is a writer and editor, and has worked with numerous academic institutions, companies and non-profits in the life sciences. BIO. Follow him on Twitter @AMPorterfield