GLP’s @JonEntine cautions against #antiscience @NASciences #GMOs panel, http://t.co/VQkA5nkc0W @GMWatch @GMOTruth @GMWatch @GMOSF

— Genetic Literacy (@GeneticLiteracy) September 18, 2014

— Genetic Literacy (@GeneticLiteracy) September 18, 2014

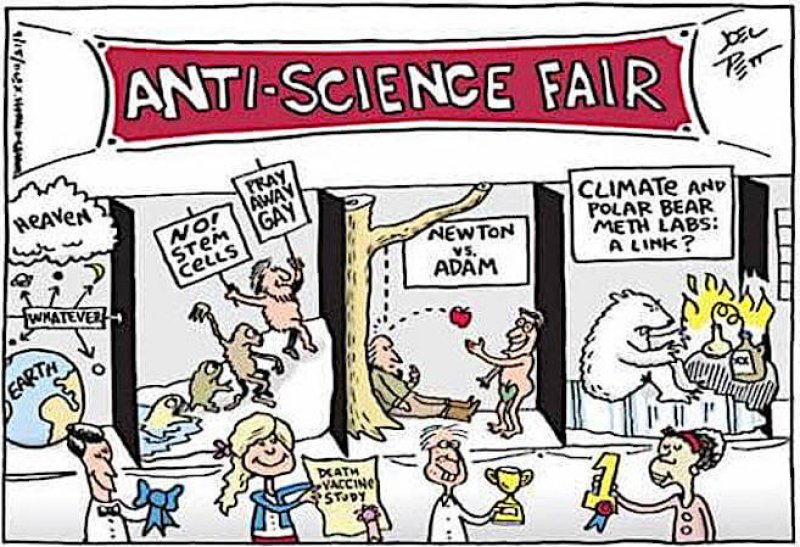

Kloor noted that GLP’s Jon Entine had not used the term “anti-science” in his remarks, but instead had explained that those who aggressively argue that GE crops are harmful, and don’t present other viewpoints, are engaging in ideology and politics rather than science, and that a Harvard panel on climate change had situated climate change denial similarly.

The underpinnings of the anti-climate change movement have given it political resonance, [Naomi] Oreskes said, because of ties to cultural traditions of independence, self-reliance, and small government.

“It becomes an argument about big government,” Oreskes said. “For Republicans in Congress and elsewhere, it’s not about climate change, it’s definitely not about science, it’s about government.”

Kloor maintained that denialist impulses are shaped more by cultural values rather than by an attitude towards the scientific method, including a respect for the weight of evidence:

So it goes with tarring someone as anti-science. Why poison the well even more? I ponder this as I continue to write about GMOs and other hot button topics. It’s relatively easy to debunk urban myths, call out false balance, shake my fist at agenda-driven fear-mongers. (I’m sure I’ll continue doing that.) But I see diminishing returns with this approach. It seems more fruitful to engage in a debate about the socio-cultural values that underlie opposition to GMOs and that inform strong views on related sustainability issues.

Along these lines, I don’t see how characterizing a person’s beliefs, a political party, or an NGO as “anti-science” is helpful. I’m sure it’s good for scoring points and sharpening the lines in a debate, but beyond that, I’m not seeing much value.

Kloor had introduced the topic by noting that the environmentalist Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., who believes that vaccines are dangerous, was stung the most by being labeled “anti-science”. Kennedy insisted he was not. However, I’m sure that Kennedy sees his views on vaccines as being informed by science as he understands his environmental stances to be.

I would concur with Kloor that no one sees themselves as being “anti-science”. The charge is rooted in the word science being used in an imprecise way. If you tell someone she is “anti-science” she will likely hear different meanings of the words and it’s unlikely that the charge will ring true or result in that person changing their viewpoint.

When people hear the word “science” they may think of the wonders of the natural world that are studied by scientists. “I love pictures of galaxies and learning about the migratory patterns of birds. How can I be “anti-science”?”

Or perhaps the charge of being “anti-science” comes bundled with a charge of Luddism, sweetened with an insinuation of hypocrisy that a denialist rant has been typed out on an iPhone. But there is nothing inherently “anti-science” or hypocritical about believing that the costs of a specific technology outweigh the benefits.

What is really being referred to in the context of the charge of “anti-science” is an “anti-scientific method”. As we learned in seventh grade, the scientific method starts with a question. Information is gathered and a hypothesis, or educated guess, is formed. We then test the hypothesis by doing an experiment. The experiment should be constructed in such a way that our hypothesis can be disproved. We analyze our observations and communicate the results. Ideally results are replicated to confirm or disprove our observations.

Where people go astray is understanding the broader, more social process of forming a scientific consensus on larger issues that can’t be resolved by single experiments.

This goes beyond designing an experiment and testing a hypothesis. Whereas the scientific method helps us separate the signal from the noise to answer a very specific question, the scientific community also takes steps to separate the signal from the noise regarding the state of the knowledge on broader topics like climate change or the safety of biotech crops. Instead of relying on single studies that confirm our beliefs, we try to look at the scientific literature in it’s totality.

An outlier study should reasonably hold up to greater scrutiny, rather than be immediately embraced, because the weight of evidence has not yet shifted; it’s just one study of many. Researchers go beyond single experiments and conduct systematic reviews of all the studies on topic and organize them into literature reviews. They group the data from like experiments into meta-analyses to gain greater statistical power. They form committees to draft consensus reports. From this larger, social process a scientific consensus forms when the evidence convincingly points in a single direction. That does not lock in that conclusion for eternity, as theories are always open to new evidence. But to reject the weight of evidence based on one or a few outliers makes no sense, and is not science.

We avoid putting politics ahead of science by committing to use the scientific method and respecting (but not blindly following) the scientific consensus first and then applying our values to what we learn, rather the letting our values dictate what we are willing to learn. That’s how we use a scientific consensus as individuals, but it also should inform our dialogue. Instead of asking loaded questions of those we disagree with, “Why are you against science? Why do you want children to go blind by opposing Golden Rice?”, we should be asking, “Why do you see a handful of poorly conducted studies as the signal and the hundreds if not thousands of well conducted studies summarized in literature reviews and meta-analyses as the noise?” Following science means we do not cherry-pick studies that reflect our predetermined values.

Instead of short circuiting the conversation, we can hopefully open a new avenue for understanding. Kloor wrote:

Now I’m not suggesting that we sugarcoat denialism of any sort, but I do think the disparaging language that takes hold in a public discourse can be off-putting to those who perhaps identify with a certain tribe but not necessarily buy into all its positions.

I would also suggest that the term “anti-GMO” is not always helpful and that “GMO critic” is a more accurate and less alienating term for those who do not embrace biotechnology in agriculture, but who are not denialist by temperament. I’m talking about those who may be inclined towards anti-corporate and naturalistic viewpoints, but who are persuaded by evidence when it is presented to them. This is a different dialogue partner than a classic “Anti” who is conspiratorial by nature, cannot be persuaded by evidence and generally buys into an entire suite of denialist beliefs. Most GMO critics are not “anti-science”, they just haven’t committed to following all the evidence where it leads. They haven’t put any checks in place to push back against confirmation bias and motivated reasoning.

Calling someone an “Anti” defines them by their opposition to something. Identities harden over time. The identity of “Critic” is be defined by critical thinking and that should be the place where we can find common ground and challenge each other to think more critically.

A version of this article originally ran on Sept. 23, 2014.

Marc Brazeau is the GLP’s senior contributing writer focusing on agricultural biotechnology. Follow him on Twitter @eatcookwrite