So, what happened?

Despite what seem like endless decades of hope, exhaustive research and unyielding effort by the world’s smartest scientists, we still have yet to find a cure or long-term treatments for cancer. But finally, we appear to be edging closer to the finish line, and immunotherapy might prove key.

Why haven’t we cured cancer yet?

For decades, the cancer treatment of choice has been chemotherapy. But, while chemotherapy can be incredibly effective at treating cancer, it takes a steep toll on human body. The side-effects of most chemotherapy treatments can be quite severe, and while the end result does often get rid of malignant cells, it also destroys plenty of healthy cells in the process.

Cancer is immensely complicated. It’s not just one disease – it can actually take over a hundred forms, and attack different parts of our body. What’s worse, what starts as one disease can mutate into something entirely different. Many tumors also contain more than one type of cancer cell.

Another challenge of treating cancer lies in the fact that there are great differences in patients’ physiologies, lifestyles, attitudes towards treatment, responses to treatment, genetic makeup and even epigenetic factors.

“Cancer is as individual as the person who has it,” explains Joyce Ohm, PhD, at the Department of Cancer Genetics and Genomics at Roswell Park Cancer Institute in Buffalo, New York.

“Let’s say there are identical twin sisters, both with breast cancer. They may have been born with exactly the same genetic mutations, but one responds to therapy and one doesn’t. One may live and one may die.”

It’s exceptionally difficult to find something that will work on everyone. Immunotherapy seeks to resolve this issue by personalizing treatments for each patient.

Evolution of immunotherapy

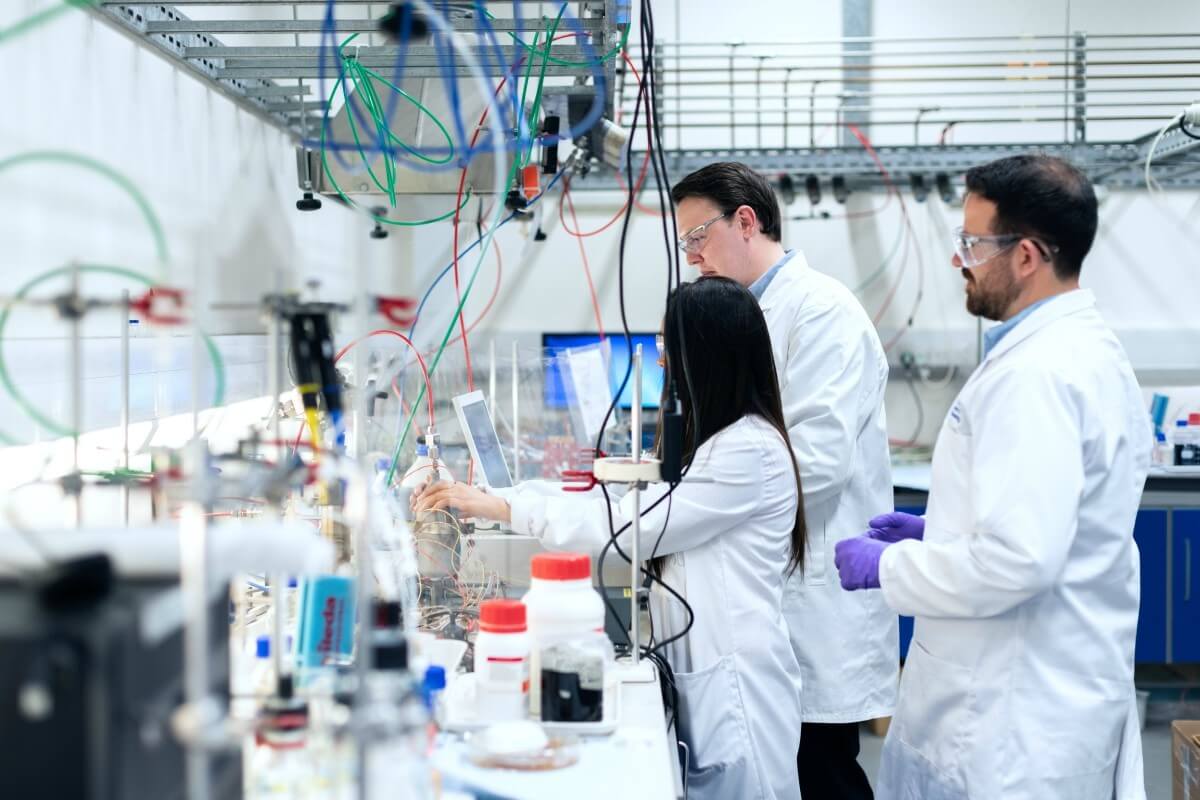

Immunotherapy isn’t a new treatment by any means; scientists have been researching it for many years, and they’ve invested a lot of time creating the right procedures and improving chances for all cancer patients.

The talk of immunotherapy started way back in 1890s, when William Coley, a physician, started researching how our immune system responds to viral infections. He hypothesized that scientists could jumpstart our natural immune response to cancer by “provoking” it with a controlled virus infection. But for years, little practical progress was made, and immunotherapy was viewed as having limited potential.

As crude as this method sounds, its basics eventually led scientists to explore how our own immune system responds to cancer and what can be done to target it without damaging other somatic cells. It also works on many types of cancers, even some that do not respond to chemotherapy or radiation.

Although immunotherapy is not yet as widely used as surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation therapy, immunotherapy drugs have been approved to treat many types of cancer. The one the doctor decides to use depends on the type of cancer they are tackling.

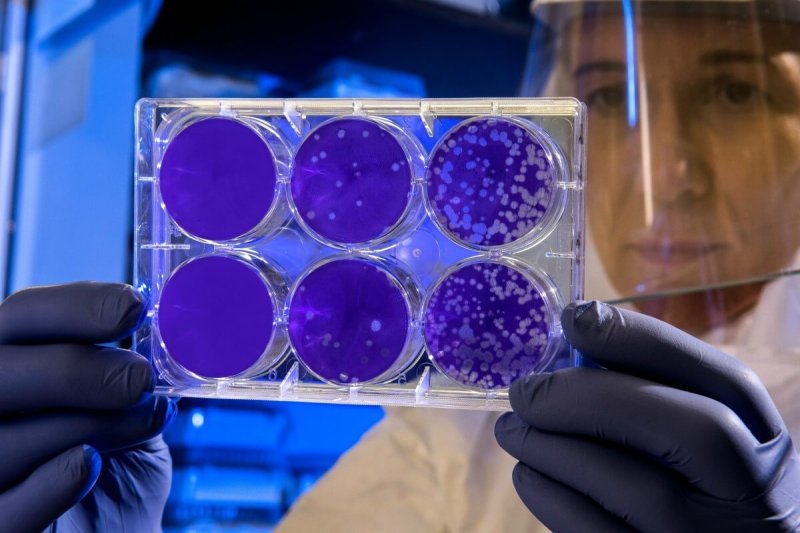

The main aim of immunotherapy today is to help activate dormant T-cells and help the immune system better recognize cancerous cells and get rid of them safely. T-cell transfer therapy basically attempts to re-engineer our immune response. It’s a complicated process but so far it has shown great success. Other cancer immunotherapy treatments include immune checkpoint inhibitors that block certain chemicals in our body from stopping immune response to cancer cells; the use of cytokines, laboratory-made versions of a type of natural protein that boosts our immune response; lab-made monoclonal antibodies that bind to specific targets on cancer cells; and treatment vaccines.

Cancer targets

The key in developing immunotherapies is finding the right cancer targets. Chow Kwan Ting, a researcher from City University of Hong Kong (CityU), who has won the famous Croucher Innovation Award in recognition of her scientific achievements, focuses on the role of plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) in cancer treatment.

These cells haven’t been researched thoroughly before, but they’re known to play an important part of immune system’s response to viral infections. Dr. Chow’s studies have shown that pDCs play a role in other types of infections as well, and that they could potentially do more than simply fight off an infection: they might actually play a role in cancer immunity.

Other scientists are advancing a range of promising immunotherapies that researchers hope will lead to breakthrough cures. A team of researchers at the German Cancer Research Center and the Berlin Institute of Health are targeting the metabolic enzyme IL4I1 (Interleukin-4-Induced-1). The survival probability of patients with gliomas, a type of malignant brain tumor, decreased when the enzyme was present in higher concentrations in these tumors.

In 2004, Sophie Lucas, a researcher at the University of Louvain de Duve Institute, began studying the blocking of immune defenses in tumors in order to understand the functioning of cells that are said to be ‘immunosuppressive’ (they block the body’s immune responses). The goal was to identify and remove them, thus stimulating antibodies to act against the tumor. Last August, Nature Communications published the results of the first tests carried out by Dr. Lucas and her team on a tool using what are called anti-GARP antibodies that prevent the body’s natural immune response from being blocked. It worked on mice; human studies are next.

Of course, more research is needed to turn immunotherapy research into potential cures, but the very fact that scientists keep learning new things about cancer treatment is encouraging. Scientists are looking into liver and breast cancer as they are more prevalent in Hong Kong than other types of cancer.

Immunotherapy can sometimes have similar side-effects as chemotherapy, such as nausea, vomiting and hair loss, but they are usually less severe. It can also be used in combination with radiation therapy or surgery.

Along with gene therapy and tumor DNA sequencing, immunotherapy is providing new options and helping us edge closer to promises made more than a century ago.

Claire Adams is a content creator and external associate of the City University of Hong Kong. Her goal is to promote CityU young scholars’ research papers that are closely related to the healthcare industry. She wishes to emphasise the importance of the research paper on rare cells and the innovative immunotherapeutic strategy, which truly brings hope to new cancer immunotherapy and vaccine. By promoting this work among the scientific and healthcare community, Claire is hoping to raise awareness of the City University of Hong Kong’s contribution to society. Follow her on Twitter @adamsnclaire