A woman lingers at a display of coffeemakers. Soon after, images of the very same contraptions festoon her Facebook feed, courtesy of her phone’s GPS and store cameras.

A man diagnosed with a blood clot gets TV ads for a drug to prevent further episodes.

A person peruses ads for indoor herb gardens for a gift and is later bombarded with botanical options on social media.

People turn 65, and suddenly Joe Namath interrupts their favorite TV shows, with unending descriptions of Medicare Supplement plans.

Coincidences? Hardly. In this age of TMI, it can feel as if our very brains are being intrusively picked, constantly. Even our DNA can be trolled for embedded preferences and habits, if we (sometimes unknowingly) provide permission.

How foreboding is the ‘privacy crisis’?

Remi Daviet, Gideon Nave, and Jerry Wind, from the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, dissect “Genetic Data: Potential Uses and Misuses in Marketing,” in a report in a special issue of the Journal of Marketing. They provide telling examples of how DNA data are beginning to become part of microtargeting, which is “a marketing strategy that uses consumer data and demographics to identify the interests of specific individuals or very small groups of like-minded individuals and influence their thoughts or actions,” according to one definition.

This is not all new; election campaigns and political parties are already pros at microtargeting.

Consumer DNA testing has opened other doors. What would happen if microtargeting considered the patterns of genome variations that turn up when we spit into tubes or swish mouth swabs, pop the samples in the mail, and find out weeks later about inherited traits or diseases risks, or ancestry?

Although sales at consumer DNA testing companies began to drop even before the arrival of COVID-19, hundreds of thousands of test kits still went out in 2020. And not everyone reads the fine print when signing off on permission for the testing company to share data with other companies, even in the future.

But DNA data sharing in advertising is already happening.

From playlists to vacation rentals

“And now your AncestryDNA results can play a unique mix of music, inspired by your origins,” announced Spotify in 2018, offering to tailor playlists.

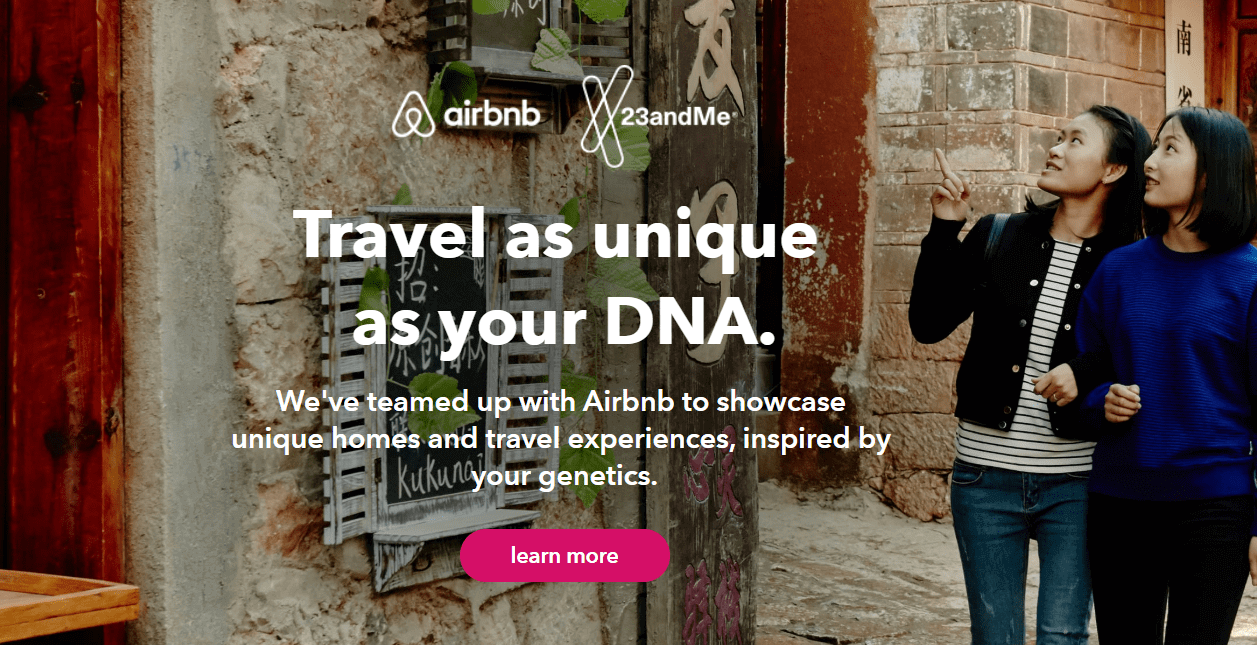

Vacation plans can also reflect genetic origin information. Planning a post-pandemic escape to an Airbnb? DNA patterns might help narrow down a destination, thanks to Airbnb’s teaming with genetic testing company 23andMe in 2019 to facilitate “heritage travel.” Critics pointed out that a tiny slice of Italian or Indian heritage on an ancestry pie chart has little to do with culture, psychology, or identity.

One company’s advertised use of consumer DNA data in promoting tourism was so outrageous that it may have been in jest. A flurry of media reports in January 2019 targeted an ad from AeroMexico offering “DNA Discounts” for certain U.S. travelers. This video features folks who don’t realize they have some “Mexican DNA.” For example, a middle-aged man sporting a black cowboy hat with “Bill” emblazoned on his khaki shirt helpfully claims to like tequila and burritos, so wonders why he’d never considered visiting Mexico. Maybe he should! But when the company refused to provide further information to and the offer never got off the ground, some journalists and genetics experts suggested the ad was a joke to criticize racists.

The researchers from the Wharton School, Daviet, Nave, and Wind, considered whether DNA information is perhaps more valuable in marketing than conventional input, such as responses to survey questions. Their reasoning was that biological information could suggest a mechanism for certain behaviors, in a way that answering questions about likes and dislikes can’t. But DNA data came up short, practically speaking.

Love of espresso is an example in the paper.

People who gave DNA samples to the UK Biobank were predicted to like espresso based on having particular variants of three genes associated with perception of bitter substances in general, and of quinine and caffeine specifically. True, a simple spit test to assess those genes is far cheaper than imaging the brain to visualize hotspots for bitter taste cravings. But why not just ask someone to point to the part of the coffee bean display at Starbucks that they prefer? A desire for a caramel macchiato with an extra shot isn’t encoded in DNA bases.

DNA data could aid microtargeting

Identifying genes could have mixed consequences. Deducing playlists, vacation destinations, and coffee preferences are trivial. But imagine getting social media ads for hair growth products because a DNA test predicts baldness? Ads for a test kit for stool collection because of a gene variant associated with increased risk of colon cancer? DNA data can predict, and that can be distressing.

Only some consumer DNA tests, though, look at single genes with well-defined effects on health. Genes have been identified that include hair loss, variants of the ACTN3 gene associated with ability to sprint versus long distance running, and ones that control production of neurotransmitters and may affect such traits as anxiety, addiction, extraversion, and even preference for fatty or sugary foods.

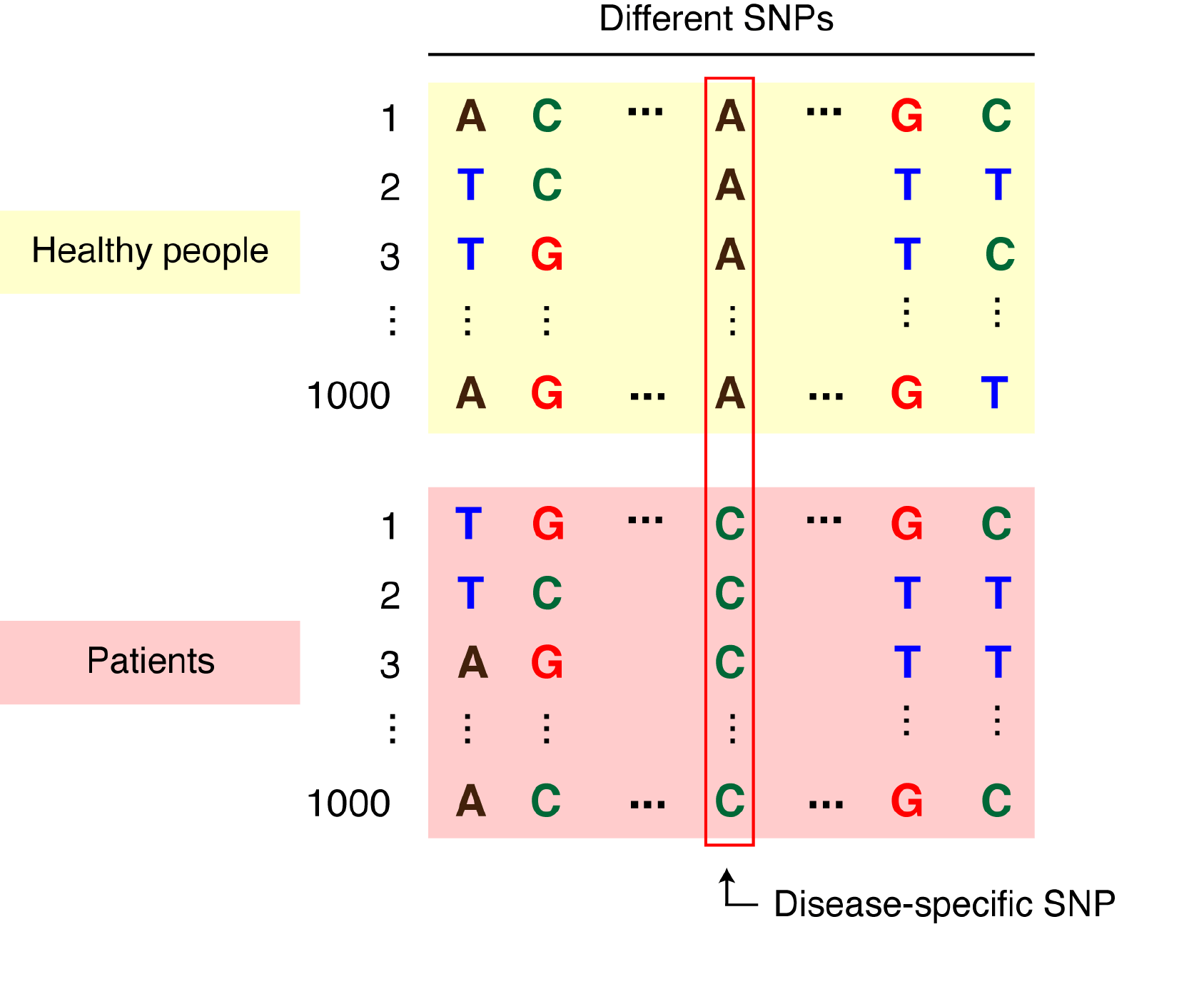

Mutations in single genes with striking effects have been important in the history of genetics, from the heights of Mendel’s pea plants to different eye colors of fruit flies to antibiotic resistance of bacteria. But consumer DNA testing is more in the form of single-DNA-base variations, called SNPs, that are peppered throughout the genome.

SNPs are like typos in the genome sequence, but patterns of them are considered as if they’re genes. Instead of encoding proteins, as genes do, SNPs serve as signposts that are compared to reveal associations. For example, people with one pattern of SNPs at the same places in the genome might share high blood pressure, and of a different pattern, low blood pressure.

We can now inexpensively identify SNPs across our entire genome. Comparing genome-wide SNPs is a little like finding a cupboard full of cake mixes and cookies and deducing that a person likes sweets, compared to the cupboard of another filled with whole grains and dried beans on the same shelves and in the same positions. SNP patterns are sometimes translated into simpler “polygenic risk scores,” and machine learning applied to extend predictions.

The special sensitivity of genetic data

Whatever the exact form and scope of genetic data, using them presents broad ethical and legal challenges. Daviet, Nave, and Wind note that:

- only a small fraction of a genome – 60 to 300 SNPs – need be known to identify a person, making anonymity difficult if not impossible, raising privacy concerns.

- genetic information applies to a person’s biological relatives too

- genetic data can predict a future health condition

- DNA can’t be changed

Said Nave in a news release:

Because of these unique features, the use of genetic data by marketers might create threats to consumer autonomy and privacy. There is also potential for misinformation because consumers’ perceptions of genetics might lead them to believe that genetic-based recommendations are always backed by solid science, which might not always be the case.

To illustrate the limitations of consumer DNA testing, the researchers cite FDA’s intervention in 2013 requiring 23andMe to provide probability statements for predictions of health conditions. “This cautionary tale illustrates how companies might use the scientific image of genetics in their consumers’ minds to oversell the utility of genetic information,” the researchers wrote.

Another source of confusion arising over DNA information: what’s missing?

Consumer DNA testing companies, for example, typically test for the three most prevalent mutations in the two most common breast cancer risk genes, BRCA1 and BRCA2. Consumers might not realize that many other genes and their variants affect the likelihood of developing breast cancer. That’s why much more complete clinical tests are required for a diagnosis.

Consumer DNA testing companies, for example, typically test for the three most prevalent mutations in the two most common breast cancer risk genes, BRCA1 and BRCA2. Consumers might not realize that many other genes and their variants affect the likelihood of developing breast cancer. That’s why much more complete clinical tests are required for a diagnosis.

Informed consent is another issue. A clinical trial participant signs off on exactly how personal data will be used, and if a new use for a tissue sample or test result comes along, new consent is required. That’s not the case for the general permission a consumer provides.

Why consumer DNA data do not add much

How valuable are the data to marketers? Here is one of thousands of potential examples: if people who love pepperoni pizza share a particular set of SNPs, that’s useful to a marketer, even if why these people love the same food can’t be pinned on a particular molecule. It doesn’t matter that genetic studies aren’t typically granular enough to determine the mechanisms behind purchasing behaviors; what does matter is the predictive value of identifying genetic patterns.

Consulting DNA information for targeting advertising may be flashy, but ultimately pointless. Here’s why.

First, DNA isn’t destiny. I’m 100 percent Ashkenazi Jewish, according to three consumer genetic testing companies and my grandparents, but I love Pitbull’s music. Searching my Pandora playlists and zumba classes saved on YouTube is far more informative than anything in my genome.

Secondly, using findings from the consumer DNA companies is genetic determinism – “we are our genes” – run amok. Not much about what makes the ‘essential us’ stems from DNA. That’s why 23andMe’s invitations to “participate in genetics research” is amusing. The inquiries aren’t related to something a gene could actually do, such as encode a protein that has an effect on health, like absence of a clotting factor causing hemophilia.

Instead, 23andMe probes a hodgepodge of traits: shoe size, hearing a conversation in a noisy restaurant (remember that?), doing puzzles while distracted, matching a melody, and various habits, hobbies and quirks. Do respondents who share a trait also share a SNP pattern? If so, the parts of the genome that the SNPs mark might harbor genes having something to do with shoe size or ability to hear above restaurant chatter.

Thirdly, genetic associations based on SNPs provide weak evidence. But at least they have the potential to lead to gene discovery and revealing a biological mechanism, which is more than “twin studies” that once dominated behavioral genetics do. Their premise is straightforward: if a trait is more common among both members of a pair of identical twins than it is among pairs of fraternal twins, then there’s an inherited component.

The marketing article also cites traits that have been the subject of twin studies and are used in targeting advertising: ability to make wise investments, altruism, and trust (important in believing ads), and cell phone call and text frequencies.

One twin study investigated “The Heritability of Duty and Voter Turnout,” based on the “belief that voting is a duty” is a heritable trait – that is, genetics contributes to the variability among individuals. There’s an entire literature on genes and politics, but it’s difficult envisioning the sorts of proteins that might make someone favor one candidate or political party over another.

Even if use of consumer DNA data in microtargeting is flawed, it’s here to stay. Conclude the authors of the new paper:

With the fast accumulation of genetic data, and the rapid advances in methodology for genetic-based inference, the use of genetic data for marketing research and practice is likely to become more and more common in the future.

Ricki Lewis has a PhD in genetics and is a science writer and author of several human genetics books. She is an adjunct professor for the Alden March Bioethics Institute at Albany Medical College. Follow her at her website or Twitter @rickilewis