As a child, I fed the mealworm stage of this beetle to my pet chameleon.

As a teen, I babysat for a family that owned a pet shop. The house was filled with animals, and I was thrilled to be there. That is, until right before bedtime.

As I was trying to get the kids upstairs, a monkey grabbed a can, leaped atop a curtain rod, whipped the top off, and happily sprayed dozens, perhaps hundreds, of writhing, fat, pale mealworms all about the living room. It was great fun collecting them.

Then a few days ago I got a news release from Paris-based Ynsect. The company’s goal: to farm massive numbers of yellow mealworms as food for humans. And I instantly remembered the creatures festooned around that long-ago living room.

Ynsect’s good news was that the yellow mealworm’s genome had finally been sequenced. Thank goodness! It was a tough one to crack.

Eating mealworms

Farming yellow mealworms for food makes sense.

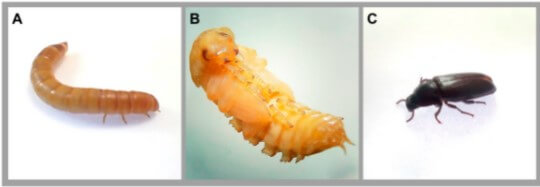

The planet will be home to more than 9 billion humans by 2050, and our species consumes bountiful animal flesh. A yellow mealworm is an animal, but being an invertebrate, its bulbous, probably chewy body is devoid of nasty bones or gristle. Orkin pest control experts provide some helpful facts about the life cycle.

Mealworms are nutritious. They can be popped into the mouth whole, like cheese doodles, or ground into powder to add to a smoothie or soup. The worms are rich in protein, a great nitrogen source, although we can’t digest the nitrogen in the crunchy chitin coats. The fats are healthy, too.

So nutritious are the worms that the European Food Safety Authority gave them a thumbs up in a 30-page report in November 2020: “Safety of dried yellow mealworm (Tenebrio molitor larva) as a novel food pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2015/228.” Here’s a short version.

.

The Authority deemed yellow mealworms ok to eat for the general population, calling them “not nutritionally disadvantageous.” That’s a triple negative. Why not say the worms seem safe and offer a recipe or two?

They concluded that the animals are nontoxic, but the legions of people who feed mealworms to their pets already know this. In fact, 2 billion people routinely eat insects, mostly in African nations.

The Authority does, however, warn that people who are allergic to dust mites or seafood might react badly to yellow mealworms, with headaches and/or asthma. But the worms are unlikely to pick up toxins in their feed, because they like to eat apples and bran. Still, the adult beetles produce a substance that can irritate human skin, should a meal metamorphose.

Farming mealworms is more environmentally friendly than raising cows, sheep, and pigs. But “despite being promising for sustainable food security, mass production of T. molitar remains relatively primitive and challenging,” the news release from Ynsect laments.

I am unfamiliar with the details of raising anything other than cats and fruit flies, and I kill most garden plants. But as a geneticist, I can appreciate the value of genetic information in breeding. Even Gregor Mendel knew that, calling the units of hereditary information “elementen” before the word “gene” arrived.

A dearth of genome information for mealworms

Projects to sequence the genomes of the species that provide our meat began in the wake of sequencing the first human genomes, near the turn of the century. Genome sequences have been available for years for cattle

cattle, pigs, and sheep. And the chicken genome sequence was published in 2004.

We also have genome sequences for blue whales, armadillos, wallabies, hyraxes, and rats and bats. The list is long, although vertebrate-centric (non invertebrate inclusive).

But mealworms aren’t being discriminated against in genome sequencing priority merely because they do not have bones. Consider the tiny, transparent roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans, a lab favorite of developmental biologists. Not only was its genome sequence genome sequence published in 1998, but for years we’ve known the journey of every one of its single cells during development, because the animal is see-through. The cells number around 1,000, differing slightly for males and hermaphrodites (no females nor fluid gender. Not sure which pronoun to use).

Meet the beetles

The genome sequence of the yellow mealworm appears in Open Research Europe, from a team from the French National Sequencing Center in Évry, France.

The mealworm genome was a tough one to crack. Attempts to map specific genes to their ten chromosomes, a typical first step, would instead shatter the genome into pieces too short to assemble into the chromosome-sized chunks needed to identify and follow agronomic traits – like growth rate, fertility, size, percent protein in the worm body, disease susceptibilities, and environmental sensitivities. Compare a genome to a book. It’s easier to identify a novel by reading a sample chapter than by listing random words scattered throughout.

We’ve paid much more attention to our own genomes. The first human gene was mapped to its chromosome in 1968. So the yellow mealworm, with its dearth of gene-chromosome assignments, is pretty far behind.

The researchers extracted DNA and RNA from T. molitor larvae. DNA comprises the genome and RNA provides a window onto gene expression – which genes are being actively transcribed and translated into proteins. They then compared the genome sequence to that of five relatives, including the familiar red flour beetle Tribolium castaneum. Several mapping and sequencing technologies were combined to get big stretches of DNA sequence and overlap the bases to derive a chromosome-by-chromosome rough genome sequence.

The stats: The yellow mealworm’s genome is about 310 million DNA bases, about a tenth the size of ours. But it has 21,435 genes, which is remarkably similar to us. Only 1.43% of the worm genes are present in heterozygous form, meaning two slightly different sequences are part of each chromosome of a pair. That seems rather genetically uniform to me. Not surprisingly, the genome most closely resembles that of the red flour beetle.

Excitement is high

“The genome, using cutting-edge methods, is of exceptional quality, with DNA sequence lengths almost as long as the chromosomes themselves. This is a major breakthrough for the sector, enabling us to begin unprecedented studies on the relationship between genes. We are at the start of a new science of this beetle and have little doubt that new properties of our insect, particularly in the fields of nutrition and health, are set to be discovered over the coming months and years,” commented Thomas Lefebvre, Ynsect’s Director of R&D BioTech Innovations.

Having the genome sequence in hand will enable “industrial genome selection.” That includes “phenotyping tools” to follow traits and “genotyping tools” to identify the gene variant combinations behind the traits.

A word on insect welfare

Ynsect isn’t the only insect farming company. Illinois-based InnovaFeed and AgriProtein from the UK are farming black soldier fly larvae for protein. But animal rights activists point out that insect farms cost trillions of larval lives a year.

A recent essay in Aeon by ethicists Jeff Sevo and Jason Schukraft addresses the animal rights aspect: “Don’t Farm Bugs: Insect farming bakes, boils and shreds animals by the trillion. It’s immoral, risky and won’t resolve the climate crisis,” the headline and subhed read.

On insect farms, ethicists Sevo and Schukraft point out, larvae meet their doom through freezing, baking, boiling, or shredding, the stress of which can promote cannibalism. Apparently no Temple Grandin of cattle slaughter fame is standing up for arthropod rights.

The ethicists discuss at length the bad things we do to insects. We poison them with flea bombs, keep them away with citronella candles, step on ants, slap mosquitoes, and spray away yellow jackets and bees.

Next, the ethicists consider the possible sentience of the six-legged, evident in the fascinating behaviors of the social insects.

I can’t argue with that, and began to feel guilty. While I’ve escorted a captured beetle or spider (an arachnid, not an insect) in an inverted Dixie cup outside for release into the wild, I’ve also, back in the day as a Drosophila geneticist, ruthlessly drowned many millions of fruit flies in tanks of mineral oil, or CO2ed them into oblivion. I’ve also killed, in the pursuit of understanding how mutations put legs on insects’ heads, mosquitoes and Tribolium, back in grad school.

I’ve eaten all sorts of plants molded into patties (see Anatomy of an Impossible Burger), but I think I’d have a hard time eating one that began as insect larvae. I just can’t erase the squirmy image. But for those unconcerned with the origin of their food, here’s a Pinterest board offering 47 mealworm recipies – from jello shots to falafel and, of course, burgers.

Enjoy!

Ricki Lewis, PH.D is a writer for PLOS and author of the book “The Forever Fix: Gene Therapy and the Boy Who Saved It.” You can check out Ricki’s website and follow Ricki on Twitter @rickilewis

A version of this article was originally posted at PLOS and is reposted here with permission. You can check out PLOS on Twitter @PLOS

This article previously appeared on the GLP on February 22, 2022.