We have seen such proclamations before, but this one is better than most. That is because this one comes with more than just instructions to implementing agencies: it comes with commands to develop specific plans to implement the order, to report back to entities with budgeting authority, and follow up with reports to demonstrate compliance. In other words, it bears the hallmarks of somebody who has been around the block and noticed all the things bureaucracies can do to delay, disrupt, and derail a president’s policies whether through ineptitude, inertia, or mischievous intent. Biden has seen this movie and it looks like he’s not here for a rerun.

As the world moves into the century of biology the United States’ longer-term fortunes will rise or fall to the extent this policy is successful. But for all the gimlet-eyed pragmatism in Biden’s approach it is not without imperfections. It focuses, understandably, on the bioeconomy as a whole, with strong emphasis on sectors it names, for each of which it provides specific guidance. But in naming the sectors for attention it leaves to the last that which properly should be first: agriculture.

It’s really very simple: agriculture is the pre-requisite and foundation of civilization. As one scholar has noted, “Civilization was built on genetically modified plants.” Without surplus production of storable food individuals would be too absorbed with the tasks of survival to develop skills in anything else. It is only with the advent of surplus, storable production that cultures became able to pursue specialization that allows them to mature into civilizations. But modern agriculture is a victim of its own success, often overlooked and taken for granted as ongoing improvements in production efficiency have made hunger, for many in industrial nations, at least, a thing of the past. But projected population growth and geopolitical crises du jour mean agriculturalists will have to produce more food in the next thirty years than they have from the dawn of humanity to the present day. This is no small challenge, and it means the hobbles impeding agricultural innovation must be discarded. Doing so would bring much low hanging fruit well within reach. How can we make this happen?

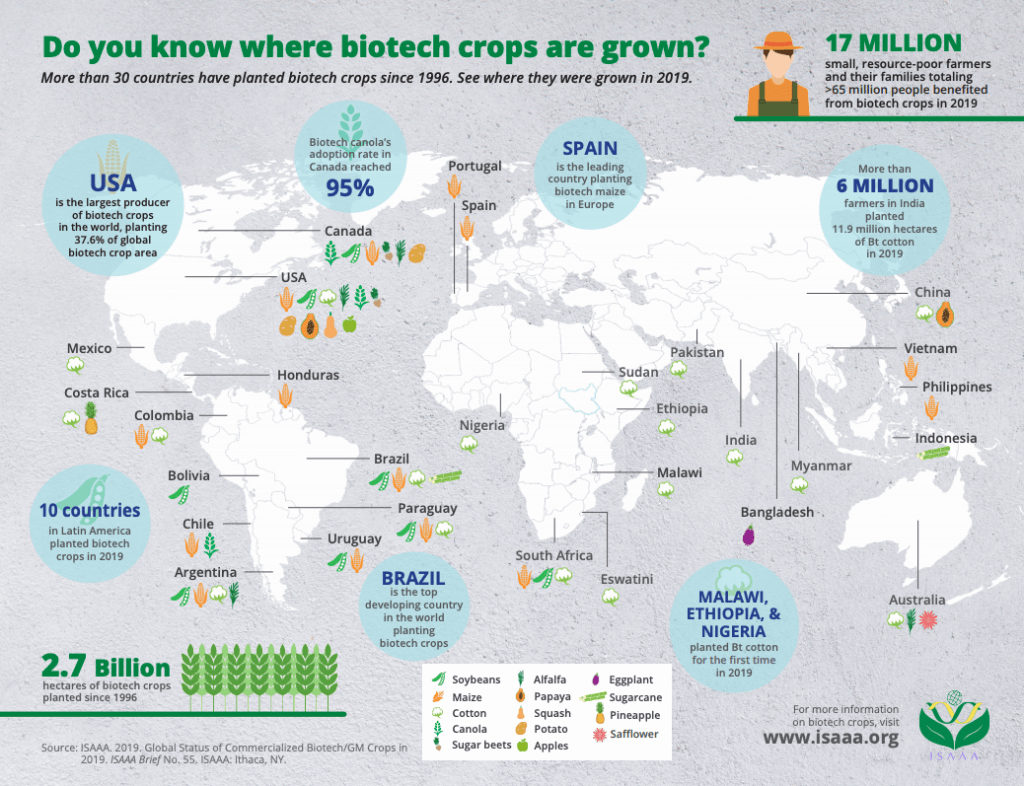

The last thirty years have seen a monumental transformation in agriculture, as modern methods of genetic improvement have been incorporated into plant and animal breeding. Vast value has been created, benefitting smallholder farmers in developing countries even more than giant farms in industrial nations. But this has happened despite ill-considered policies in most nations aimed at ensuring safety. Experience has shown the regulations put in place have been excessive, adding little or nothing to safety. Hundreds of billions of tons of “GMOs” (“genetically modified organisms”) have been produced and consumed by humans and livestock with unprecedented safety and enormous environmental and economic benefit. Yet despite this unparalleled track record new varieties of plants and animals improved with the most modern methods continue to be saddled with far more onerous regulatory hurdles than the fruits of older, less precise technologies with poorer (though still impressive) safety records.

We know what it is about food and feed that causes illness and death: microbial contamination due to improper preparation methods, or the presence of toxins and food allergens. Methods of genetic improvement neither create nor exacerbate these problems, and in fact provide new tools to further reduce them. So why are the fruits of the most modern genetic improvement techniques subjected to the most burdensome regulatory reviews? This makes no sense.

Biden’s Executive Order makes a nod in the direction of this reality, requiring agencies to “clarify and streamline regulations in service of a science- and risk-based, predictable, efficient, and transparent system to support the safe use of products of biotechnology.”This is good, but similar, previous exhortations have not borne fruit. The EO’s mechanisms for following up and deadlines for reporting back offer the hope things will go better this time, but in the past such instructions have not been brought to life, and even, in some cases, actively resisted. Biden needs to deliver more. What should the agencies do to fix the problems with existing regulations?

The first thing to do is refresh understanding of the “Coordinated Framework.” Promulgated in 1986, before many of today’s regulators were born, the CF codified the findings of several years of Congressional Hearings, and consideration by the National Academies of Science and regulatory agencies as to how the products of in vitro recombinant DNA research and development should be regulated. The CF noted that despite considerable anxiety in some quarters over the potential dangers of powerful new biotechnologies, no one had been able to identify a plausible novel hazard. Although there may be in some cases a hazard associated with a particular technology application, they are familiar – we’ve seen them before in the course of using older methods of genetic improvement, like classical plant breeding and the domestication of animals. We have experience managing and mitigating risks from exposure to such hazards – we’ve been doing it for milennia. It followed, then, that existing regulation and authorities provide a reasonable starting point, and the CF mandated agencies (USDA, EPA, and FDA) to apply those authorities to the new products. USDA was quickest and most successful in doing so, followed by FDA, and EPA. The consequence has been that agriculture has been transformed for the better, though applications in food technology have not kept pace, and the microbial applications under EPA’s jurisdiction have failed to flourish.

(ARMS) Phase II corn survey.

But even under the CF, it takes many years (~13) and millions of dollars (~130) to bring most new ag biotech innovations to market. For products that present no novel hazards, have an unmatched safety record, and have delivered massive economic and environmental benefits, this represents a massive policy failure. It has happened because USDA, FDA, and EPA have failed to update their regulations in a timely manner. They have each made some efforts in this regard, most notably USDA, but they have all fallen far short. The reason is they have lost sight of the principles laid down in the Coordinated Framework in 1986. The result is there is today a chasm between present regulatory approaches and those that could be supported on the basis of science and experience.

Sound risk management must be grounded in science-based risk assessment, which itself requires a prior finding of hazard. If there is no hazard, there is no justification for regulation. If the agencies applied these first principles they would wipe most of the regulatory oversight they presently administer from the books forthwith. But instead, remarkably, FDA presupposes the use of gene editing in livestock is so hazardous it must be forbidden until proven safe, even if used to produce phenotypes identical to those already present in existing livestock herds. This is madness.

Regulations that are fit-for-purpose share several characteristics: they start with the identification of a hazard; they proceed to a science-based risk assessment; and they implement measures to mitigate or manage the risk that are proportional to the hazards involved, and not excessive to what is required to manage exposures to the hazard. None of the US agencies presently have policies that meet these standards. Until they do they will be obstructors, not enablers, of the policies President Biden has laid down.

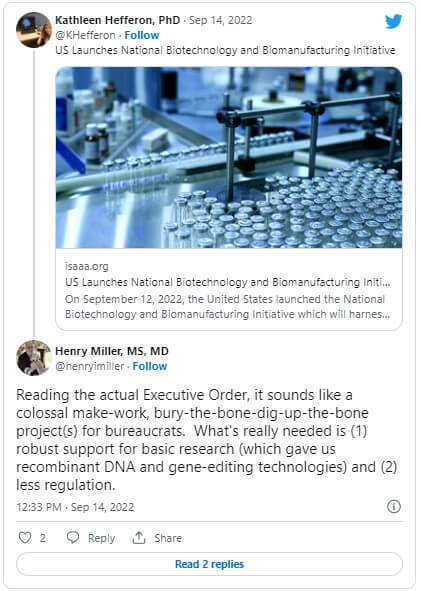

In the final analysis, what is needed is captured well in a recent tweet:

[Editor’s note: Title edited 9-26-2022 at 9am ET.]

Val Giddings received his Ph.D. in genetics and evolutionary biology from the University of Hawaii. Val is also president/CEO of PrometheusAB, Inc, and senior fellow at the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation. You can follow Val on Twitter @prometheusgreen

A version of this article originally appeared at Information Technology and Innovation Foundation and is used here with permission. Check out Information Technology and Innovation Foundation on Twitter @ITIFdc