It’s less than half a mile from the crowded marina to the site of cannibalistic excess — at least, that’s the distance in space; in time, they’re more than 50,000 years apart. Welcome to San Felice Circeo, an Italian tourist town on the Tyrrhenian Sea, roughly halfway between Naples and Rome.

This seaside resort presents a vivid microcosm of Italy’s present and past, from its swanky modern villas and multi-million dollar yachts, back through a rich antiquity to a more murky prehistory, complete with an infamous Paleolithic ‘crime’.

San Felice Circeo also provides a glance at Italy’s (and indeed Europe’s) ann underappreciate transformation evolving across Europe — a future signalled by hand-written warnings in the surrounding countryside: “Lupi di notte” —”wolves at night”.

Europe, with its aging population and plummeting birth rate, is rapidly ‘rewilding’ —enabling nature to shape land and sea, repair damaged ecosystems and restore degraded landscapes. Through rewilding, wildlife’s natural rhythms create wilder, more biodiverse habitats. And that’s what is occurring in parts of Europe, with ever-expanding areas of abandoned former farmland reverting to nature.

This dramatic social and environmental transformation, now seen as Europe’s “new normal”, is addressed in a recent conservation report, Wildlife Comeback in Europe. This study presents a largely optimistic picture of the “increases in both range sizes and population abundance” of many species. And there is no doubt, as the non-profit “Rewilding Europe” documents, it’s been remarkably successful helping to revive almost-lost species and threatened ecosystems.

As the NGO states on its site:

Rewilding Europe is creating space for natural processes like forest regeneration, free flowing rivers, herbivory and carnivory to impact ecosystems. Across the continent, the interaction of these processes leads to constantly evolving landscapes rather than fixed habitats. A forest today can be a grassland in a few years, and vice versa. Understanding this dynamic – the ever-changing habitats in space and time – is the key to preserving Europe’s rich biodiversity.

Yes, in some key ways it is an optimistic development for the continued advance of nature. But there is a flip side that should temper some of the enthusiasm pushing this movement forward, as tweaking ecosytems can have unintended consequences, some of which are not currently part of the public conversation: Rewilding is only possible as more and more people abandon farmland and rural areas as the human population of rural areas all across the continent accelerates.

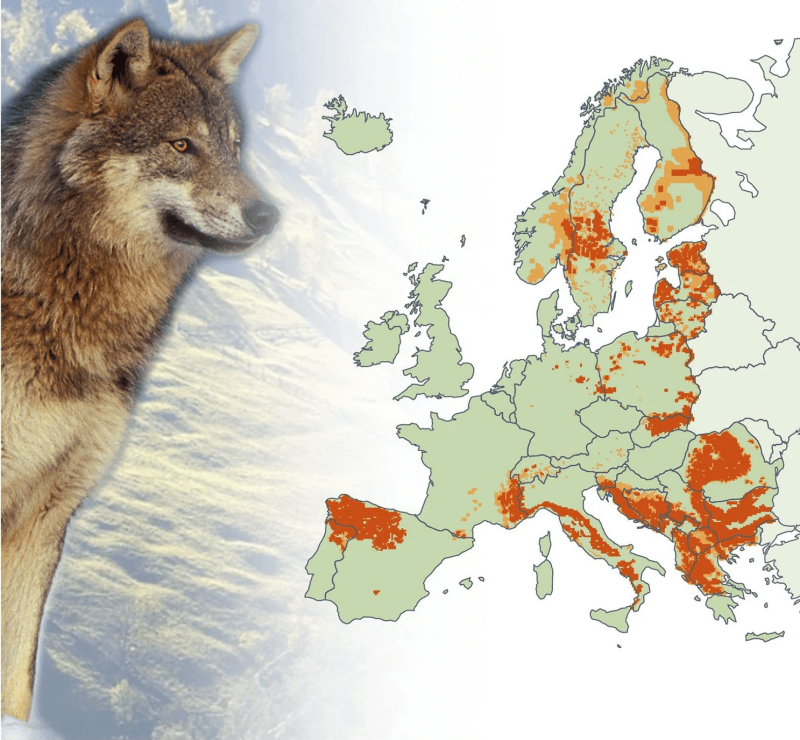

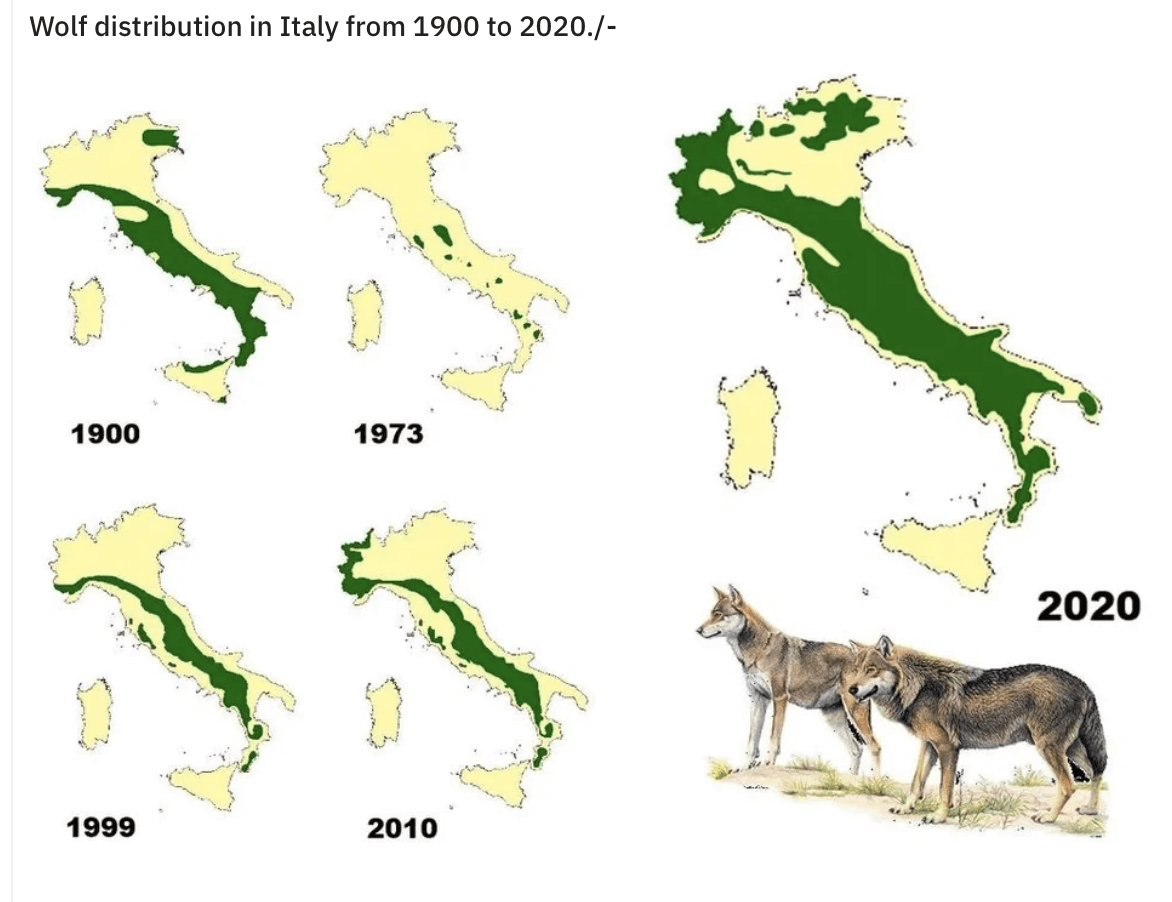

Italy (with Europe’s average oldest people and lowest birth rate) is at the forefront of the rewilding movement with a resultant resurgence of some natural habitats. But it’s also experiencing rural depopulation, and that problem is accelerating. The recent “spectacular” expansion of the Italian wolf, for example, rescued from near extinction, is one indicator of this trend and hence many “Lupi” warning signs in San Felice Circeo’s hilly hinterland.

For rewilding advocates, this is a cause for celebration. Italy, they say, is moving from a country of crowded “cafes and colonnades” to its ‘wild heart’, “a land both wild and wondrous … inhabited by bears, wolves and wild boar, and skies patrolled by golden eagles and griffon vultures”.

It’s an intoxicating, romantic vision. But is rewilding really as “wild and wondrous” as its supporters believe? Here’s where San Felice Circeo comes in (cannibals and all). This seaside ‘commune’ provides a useful lens to assess both the costs and the benefits of rewilding in Italy and Europe.

Myth and history, caves and cannibals

To fully evaluate this process today — and how it could play out tomorrow — we first need to look back to yesterday. So let’s begin with San Felice’s fabled past.

Long-standing legend links San Felice Circeo to the island of Circe, the sorceress in Homer’s epic Odyssey (Monte Circeo, the promontory that dominates the district, looks like an island from afar). And the town’s real recorded history is equally compelling. Initially settled by Italic peoples during the Bronze Age, San Felice Circeo was a thriving port in Roman times before being sacked by Germanic tribes (and, later, Arab Saracens) in the turbulence following the fall of Rome. Eventually absorbed into the medieval Papal States, it was one of the last holdouts in the 19th century ‘Risorgimento’, the long struggle for Italian unification.

A clue to the town’s much longer prehistory, however, comes in the name of a local guesthouse: Hotel Neanderthal, which was built in an attempt to cash in on the discoveries.

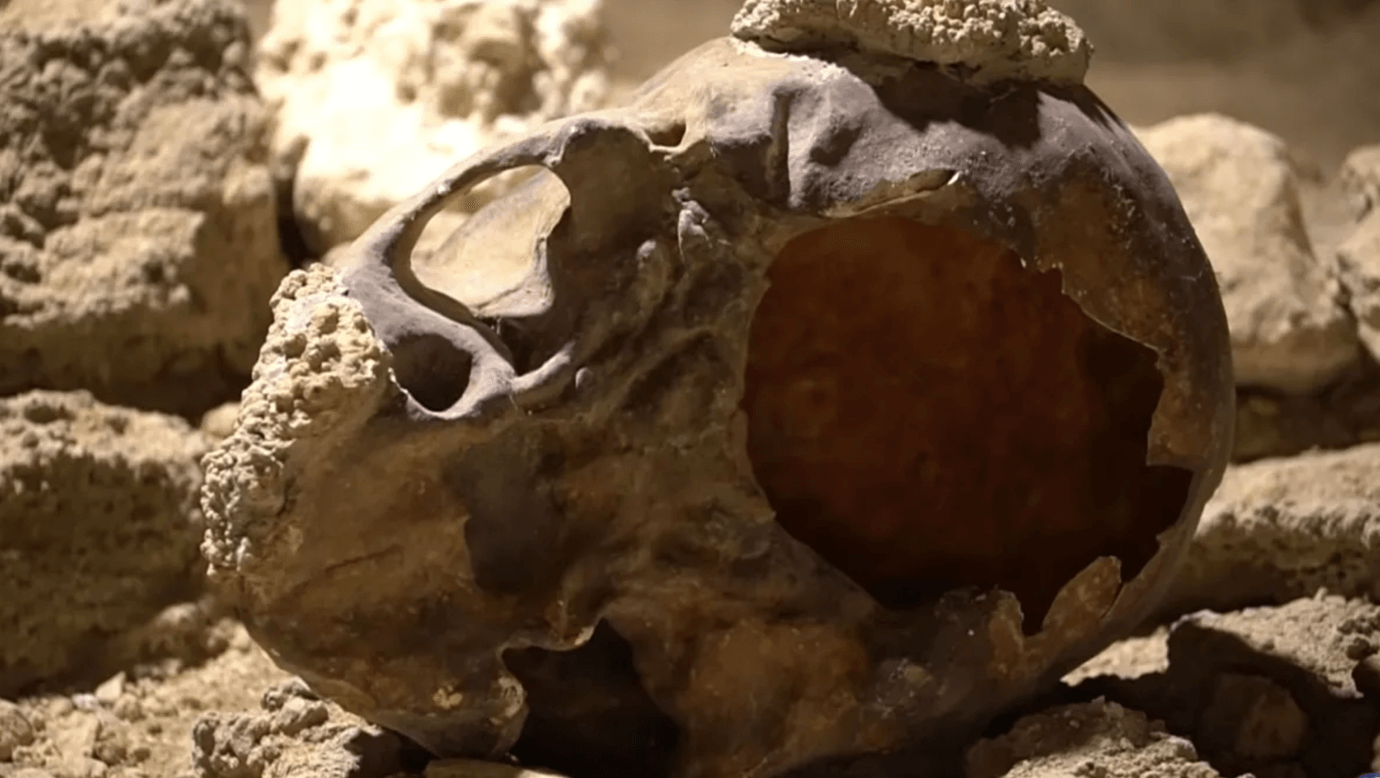

In 1939, a Neanderthal skull was uncovered in Grotto Guattari, a nearby cave. The discovery quickly became a sensation; the skull seemed to have been deliberately broken to access the brain, leading to a lurid claim “that the ancient inhabitants of San Felice Circeo … practiced rituals of cannibalism”. Not surprisingly, this notoriety helped fuel the enduring popular image of Neanderthals as brutish cavemen, more beast-like than human.

In 2019, exactly 80 years after the initial Guattari find, the bones of a further nine Neanderthals were unearthed, alongside those of horses, giant deer, elephants and rhinoceroses. An archaeological analysis suggested that these remains, the Neanderthals’ included, were the likely prey of Pleistocene hyenas, who’d dragged the victims back to their Monte Circeo den.

What then of the claims of cannibalism? Eight decades after the initial Guattari find, this question is now largely beside the point. While numerous studies do indeed provide “unambiguous evidence of Neanderthal cannibalism”, this is likely true of all species within the Homo lineage, our own included (early human inhabitants of Gough’s Cave in England, for example, practiced “a sophisticated culture of butchering and carving human remains”).

And thanks to more recent scientific research — increasingly aided by genetics and ancient DNA — we now know that Neanderthals cannot be singled out as lurching, bloodthirsty brutes as has been the case for decades. They were large-brained and intelligent, with complex behaviors that included tool-making, the use of fire and (most likely) symbolic art and language. Neanderthals even interbred with modern humans (a finding that helped propel geneticist Svante Pääbo to last year’s Nobel Prize), leaving their status as a separate species open to debate.

While San Felice Circeo is now undoubtedly “one of the most significant places in the world for the history of Neanderthals”, what relevance has this to modern rewilding in Italy or wider Europe? Essentially, the Grotto Guattari discoveries raise awkward questions about what “rewilding” actually means.

Naturally man-made?

While rewilding means different things to different people, at its most basic, according to Rewilding Europe, it is simply allowing wildlife to flourish: “It’s about letting nature take care of itself … Nature knows best when it comes to survival and self-governance.”

That’s a naive (indeed, potentially dangerous) claim. Nature is not benevolent and wise; it’s brutal and blind, with a clear and bloody example being the bones in the ancient hyenas’ den beneath Monte Circeo. Prehistoric San Felice Ciceo doesn’t just epitomize “Nature red in tooth and claw”; the human bones in Grotto Guattari also demonstrate the depth of our own species’ (and of our relatives’) existence in Europe.

Neanderthals were present for at least 100,000 years at Monte Circeo and over 400,000 years as a species. Other archaic humans, such as H. heidelbergensis or Italy’s own “Crepano man” (found inland from San Felice Circeo), push humanity’s known presence in the Italian peninsula back well over half a million years. The oldest European human fossil found to date is perhaps three times that age.

Humans (or, at least, members of the genus Homo), therefore, have been part of Europe’s natural environment for well over a million years. Our ancestors were as much a product of nature as any other species. Today, however, our species is often seen as distinct or divorced from the rest of the natural world; indeed, we’re regarded as somehow unnatural.

Similarly, the original or pristine “state of nature” is often taken as that which existed before the disruptive and destructive arrival of human beings — in biblical terms before Adam and Eve screwed things up.

Yet in the case of Europe, this seems decidedly arbitrary; was the pre-human ecology of Europe (say, 2 million years ago) any more natural than that before the advent of agriculture (c. 10,000 years ago) or before the Industrial Revolution from the 19th century onwards? If so, how and why?

Patrick Whittle has a PhD in philosophy and is a freelance writer with a particular interest in the social and political implications of modern biological science. Follow him on his website patrickmichaelwhittle.com or on Twitter @WhittlePM