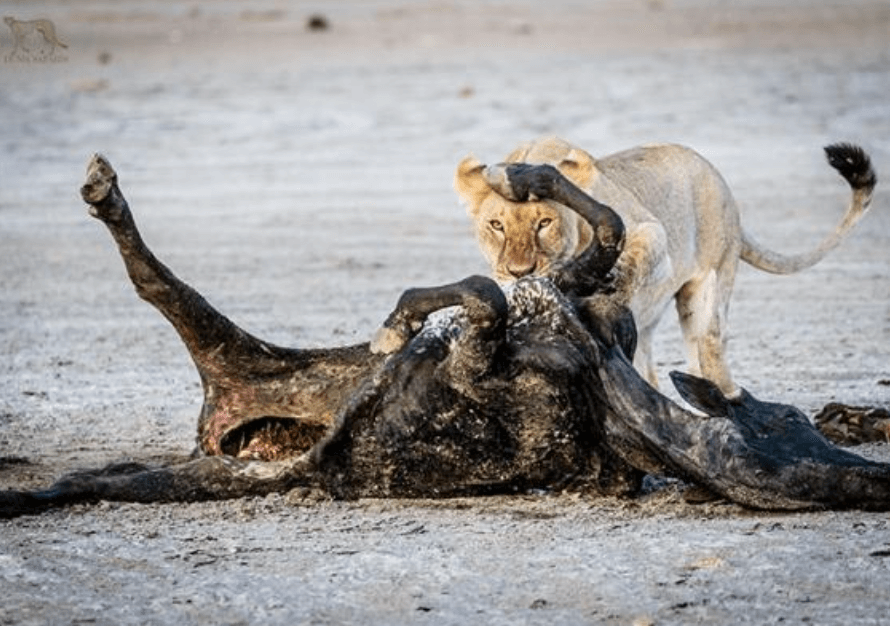

The rewilding movement, despite the optimistic hopes of the movement, poses complications. Note the cover featured picture. The 2018 article in UK’s The Guardian reported:

A scheme to rewild marshland east of Amsterdam has been savaged by an official report and sparked public protest after deer, horses and cattle died over the winter.

In a blow to the rewilding vision of renowned ecologists, a special committee has criticised the authorities for allowing populations of large herbivores to rise unchecked at Oostvaardersplassen, causing trees to die and wild bird populations to decline.

Nature can be unpredictable, often foiling the best of intentions. And rewilding experiments gone awry are only a fraction of the controversial issues raised by this movement. According to skeptics, it is chipping away at rural living and the food production in rural areas that many countries rely upon. As rural agricultural areas increasingly succumb to suburbia, the loss of natural habitats is often in conflict with the preservation of farming and ranching lands and the activities upon them is equally, if not more important.

There is an essential fuzziness to the very notion of rewilding. Are the bears, wolves and wild boar lauded by Italy’s present-day conservationists more or less natural than the horses, giant deer, elephants and rhinoceroses (not to mention Neanderthals) of San Felice Circeo c. 50,000 years ago? What species represent a truly natural, rewilded Italy?

If ecological arguments can be presented for deer and boar, say, couldn’t similar justifications be used for the reintroduction of elephants and rhinoceroses? And if wolves and bears are accepted as part of Italy’s natural environment, why not other original large carnivores like hyenas? (Proponents of deextinction, meanwhile, even advocate using genetic technology to resurrect extinct species such as aurochs and mammoths as a means to recreate lost ecosystems).

This then raises yet another issue, of the interaction between human beings and potentially dangerous wild animals. As the “Wildlife Comeback in Europe” report acknowledges, “Living alongside these species can bring tensions and conflict, particularly among those who perceive or experience an elevated risk to their personal safety”.

This is not just about (often overblown) fears of “lupi di notte” or wolf attacks on humans. Italian farmers already complain about the threat of swelling deer populations to their livelihoods, both through eating crops and by attracting wolves that they claim would soon turn to easier domesticated prey. Certainly, reported attacks on livestock have increased in line with wolf numbers (a continent-wide problem that has recently even impacted the EU President, as a wild wolf mauled the EU president’s prized pony in Janaury.

Italy’s exploding wild boar population, meanwhile, has resulted in nearly 2.5 million of these animals now roaming the countryside — and, increasingly, the towns. Over 20,000 wild boar are thought to reside in Rome alone, with “multiple cases of porcine aggression toward people” recorded. This being the case, the standard “nature knows best” defence of rewilding looks increasingly simplistic.

The cultural and economic costs of rewilding

Let’s return to San Felice Circeo. Snobbery notwithstanding, the modern town’s luxury yachts, villas and mass market tourism exemplify the crass consumerism often seen as the root of the modern world’s most pressing problems, from widening inequality to resource depletion to the climate crisis. Indeed, Italy itself is often seen as synonymous with other symbols of materialism: food, fashion and fast cars. And, of course, the vacuousness of consumer capitalism is also a key contrast drawn in many conservationists’ rose-tinted portrayal of nature.

Just inland from San Felice Circeo, however, another facet of modern Italian life can also be discerned. From the medieval walls of hilltop villages such as Maenza or Roccasecca dei Volsci, the island-like outline of Monte Circeo dominates the western horizon (“dei Volsci” recalls the Volsci people who inhabited the region in pre-Roman times.) Yet these ancient villages’ maze-like lanes and alleys are not dominated by the same gaudy consumerist status symbols — SUVs and the like — as San Felice Circeo. Instead, these old towns, like so many throughout the country, are slowly dying, with their centuries-old olive groves largely abandoned and “In vendita” (“For sale”) signs plastering the decaying houses.

Thus, just as the wolf is the poster child of resurgent nature, San Felice Circeo’s hinterland is the sad face of rewilding’s reluctant twin — rural depopulation. A way of life stretching back beyond Roman times is quietly fading. And little wonder. These quaint old villages are not equipped for modern living; there are no jobs for the young and the steep narrow streets are no good for the old.

Of course, it’s as easy to sentimentalize rustic village life — something that bargain home-hunters, drawn by Italian village house prices as low €1, may find to their personal if not financial cost — as it is to over-romaticize nature. With rewilding especially, the emotional appeal is particularly strong: as one typical account puts it,

For many conservationists … rewilding is as much an activity of the heart as of the land.

Yet there are economic consequences in the ‘ return of nature’ movement. Opposition to rewilding is strongest in rural agricultural communities. Although many farmers support the rewilding movement in limited turns, it can pose real dangers — not only to their livelihoods but to global food security. Many farmers believe that we cannot afford to sacrifice food production for what they believe is a largely romantic movement, especially when the world’s need for food demand is anticipated by the United Nations to increase by 100% by 2050. Many farmers globally have voiced their concerns. In North America, for example, the rewilding efforts have led to a surge in apex predator populations with increasing attacks on livestock and humans as well as devastation to wild herd animals like elk and deer.

Another unanticipated consequence is the mixed benefits of increased ecotourism. Newly emerging wilderness areas create a lucrative market for eco-tourism. In Italy, for instance, rewilding advocates claim that such nature tourism also helps “people, previously struggling to be able to remain in their villages …, [to find] new, additional or alternative sources of income from wildlife, wild values and wild nature”. Everyone, according to this claim, is a winner.

If only it was that simple. While ecotourism does have growing potential, it is wishful thinking to believe it could replace laborintensive traditional rural economies or slow or reverse plummeting population trends. Nature tourism will only be a niche market, and will mostly benefit only those wealthy enough to afford it.

Tellingly, similar optimism about a tourist boom surfaced in San Felice Circeo after the discovery of the latest haul of Neanderthal remains. The anticipated influx of scientifically-minded visitors, however, has thus far failed to materialize, with Guattari Grotto fenced off and Hotel Neanderthal now closed and up for sale. The town’s attraction, it seems, is still for those seeking sun, sea and sand, and not science.

In addition, while nature tourism sells itself as an eco-friendly alternative to the shallow materialism of mass tourism, it’s firmly part of the same ecologically-questionable holiday industry; eco-tourists still travel using the same airplanes and highways as their plebian counterparts. There’s also the whiff of virtue signaling and social elitism, with affluent travellers serviced by a suitably rustic peasantry (with the former not the latter having the freedom to lead more varied lives elsewhere).

The (human) value of nature

While the reality may puncture the romantic bubble of rewilding, it says little about whether the rewilding of Europe and the commensurate decline of rural communities are more positive than negative. Here’s where Italy’s long history and prehistory provide a useful perspective. Was the demise of San Felice Circeo’s Neanderthals a good thing or a bad thing; what about the rise and fall of Rome?

All we can really say is, they happened. From perspective, the only constant is change: societies change, ecosystems change, life changes. While traditionalists and romantic rewilders might believe otherwise, there is no real “natural” order as the Darwinian explanation of life makes clear, nature — of which us humans are an integral part — is in constant adaptive flux.

Unlike San Felice Circeo’s Neanderthals, however, or its Roman and medieval citizens, modern societies are no longer simply the hapless victims of circumstance. We are, if as yet imperfectly, more and more able to predict and control the consequences of our actions and to weather unexpected and hitherto devastating events, such as disease pandemics. True, rural depopulation and Europe’s consequent rewilding is perhaps unstoppable — at least not without costly and likely unsustainable intervention; but this does not mean that we cannot manage this process in ways that bring the most benefit to the most people. Here eco-tourism could play a useful part, inasmuch as it genuinely provides worthwhile and fulfilling employment.

While the full political, social and economic ramifications of rural depopulation/rewilding are beyond the scope of this essay, being pragmatic and realistic is a good place to start. Rewilding may indeed be good for nature (however that is defined) and is likely good for humans, not least the mental health benefits of access to natural environments or in helping to mitigate the long-term negative consequences of climate change. But it also has downsides, especially in its connection to the demise of traditional rural communities and the disruption of family and social lives.

Nor does nature know best. If humans and wildlife are to co-exist without conflict, nature needs to be managed. Nature also doesn’t care whether wolves and boar or hyenas and Neanderthals roam the Italian peninsula; species extinction is as natural as species expansion. The only being with the sensitivity and intelligence to care is us Homo sapiens.

Being pragmatic and realistic would emphasize the functional or practical value of rewilding (how it benefits us humans) rather than nature’s intrinsic worth in and of itself. This runs counter to broad environmentalist thinking; as some rewilders argue, “rewilding … has grown in reaction against predominant ego, or anthropocentric human values, which place the self or humans above all others. Instead, rewilding promotes ecocentrism … [and] acknowledges, like biocentrism, other species’ intrinsic value”. Yet this is an emotional human claim; to underscore the point made above, amoral nature simply does not care.

And it is a claim that is difficult to defend in conservationists’ own terms; rewilding makes much of the return of native or pre-existing species, but on what grounds (other than instrumental ones) are these intrinsically more valuable than introduced or invasive species?

Or consider the early humans of San Felice Circeo from nature’s amoral perspective. Neanderthal victims of hyena predation were no more or less valuable than any of the other species butchered and consumed in Grotto Guattari. But this put the lives and deaths of intelligent, conscious human beings as on par with those of horses or deer — an inhumane and misanthropic vision than appears worse than the anthropocentric “humans above all others” alternative. True, this too is an emotional point, but it is based on the fact that humans, through the natural process of evolution, have developed imaginations and desires and fears, and hence a greater capacity for both enjoyment and suffering than any other species.

Pragmatic natural coexistence

Even if we place human needs above those of other species — which would include parasites, disease organisms and “all things sick and cancerous” — an anthropocentric perspective doesn’t mean that nature need ‘suffer’ (not that ‘nature’ can actually suffer; ironically, that’s an anthropocentric idea). Italian eco-tourism and nature tourism in general, despite limitations, are examples of the potential for mutually beneficial human/nature coexistence.

Eco-modernists take this further, arguing that “that both human prosperity and an ecologically vibrant planet are not only possible, but also inseparable” (albeit that such “an optimistic view toward human capacities and the future” attracts strident criticism from established conservationists).

A more realistic perspective would indeed ‘re-center’ human beings — the very definition of anthropocentrism. If we cut through rewilding’s romanticism and wishful thinking, the crucial factor is not the intrinsic benefit of wilderness but that flourishing nature can help bring about and enhance flourishing human lives.

The Neanderthals of Mount Circeo lived (and died) in a state of nature. Imagine if these prehistoric humans were transported through time and space to modern San Felice Cicero. What would they think of modern human existence? Would they swap their lives for ours? Would you swap your life for theirs?

Patrick Whittle has a PhD in philosophy and is a freelance writer with a particular interest in the social and political implications of modern biological science. Follow him on his website patrickmichaelwhittle.com or on Twitter @WhittlePM