Important questions loom, now that European sugar beet and oilseed rape farmers face a potential ban on the use of seeds coated with a class of insecticides called neonicotinoids that provide effective control of aphids carrying the crop-devastating yellow virus.

How will farmers be able to continue growing these crops given there are no current effective alternative forms of control? Will the ruling extend to banning the use of all emergency exemptions, known as derogations, permitting the use of other banned pesticides? Will the ruling result in the banning of emergency derogations permitting the routine and widespread use of ‘banned’ products still widely used in the organic sector?

Or will there be a political compromise?

The background

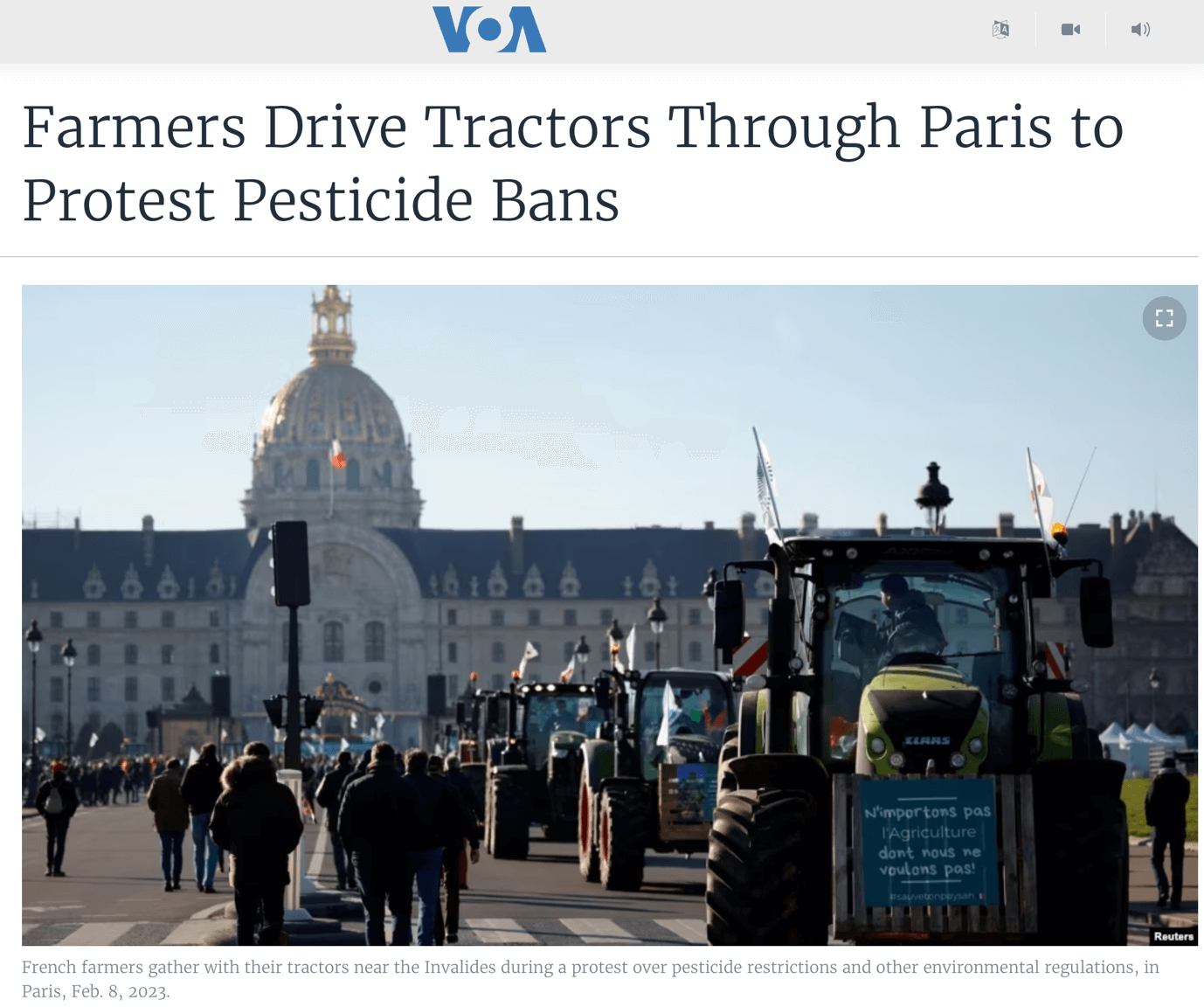

Farmers who know from experience the major yield losses yellow virus can cause — sugar beet yields in France dropped as much as 50% in recent years — have mobilized to protest against the Court ruling. Almost one thousand descended on Paris to protest in early February.

The class of pesticides called neonicotinoids, include imidacloprid, clothianidin and thiamethoxam. They have been used in many countries around the world to control disease carrying pests that can destroy crops. They have also been used in European agriculture for many years to control aphids that can infest arable crops like sugar beet and oilseed rape with yellow virus and lead to major yield losses. These insecticides can be applied to the crops during the growing season or, to help reduce the need to spray insecticides, as a preventative coating of the seed before planting.

Neonics target disease-carrying aphids that infest arable crops like sugar beet and oilseed rape. They are sprayed on crops but are also often used preventatively by coating the seeds — a technique designed to limit the amount of the pesticides used — before the plant is even infested by pests.

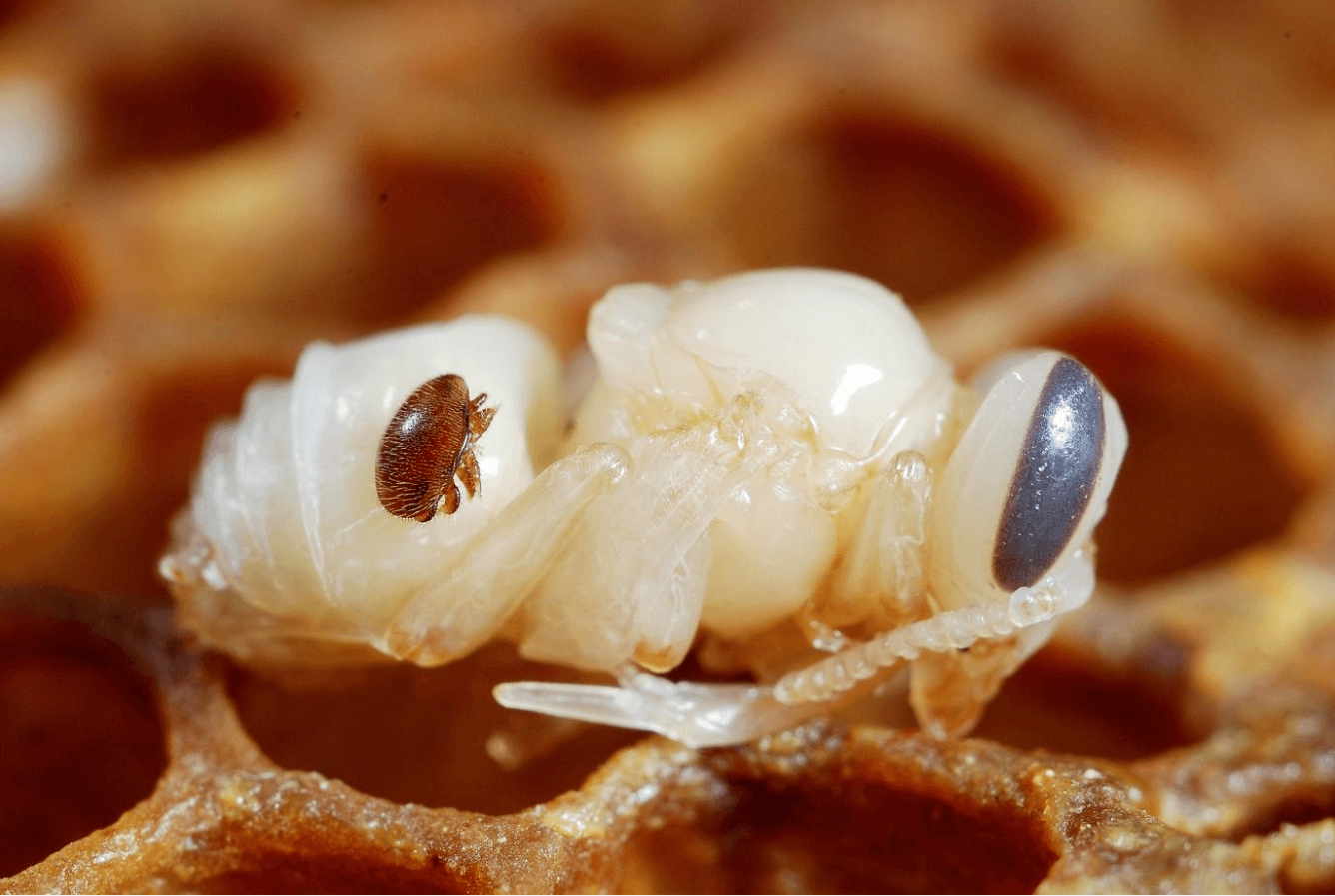

They are known as systemic insecticides. They can transfer from the soil through the sap of the plants and reach the nectar glands at the time of pollination, when the pollinators are attracted to the flowers. The question whether this harms bees and other pollinators has split scientists.

The use of neonicotinoids has been linked in some studies, mostly in laboratory settings to harming bees and other pollinators, contributing to a decline in their populations. While bee declines have multiple causes which may include parasites like Varrora mites, pathogens, nutrition, habitat loss caused by urbanization and the culling of forests, climate change, and pesticides, the data are contested.

Some scientists say much of the evidence on neonics relies on less reliable laboratory studies while in-field research shows fewer impacts, and advocacy groups have misrepresented the data. But other scientists and environmental activists, citing numerous studies, contend that evidence of the dangers of cumulative exposure to bees is persuasive.

Despite ongoing disagreement in the science community, the European Union, citing the precautionary principle, banned the use of neonicotinoid insecticides in 2018. Farmers were critical of the decision because there are no substitutes that are known to be safer or as effective.

After widespread yield losses experienced by sugar beet farmers in 2020 largely arising from yellow virus infections, sugar beet grower groups in some Member States applied for emergency authorisations to use neonicotinoid seed treatments. In France, a derogation was issued for the three years up to and including the 2023 season.

A case against the use of these emergency authorizations was filed in Belgium by the anti-pesticide groups Pesticide Action Network Europe (PAN) and Nature et Progrès Belgique. This was then passed to the European Court of Justice (CJEU), which recently issued its judgement potentially banning the use of these derogations. EU member states are now awaiting the EU Commission to issue a formal interpretation of the ambiguous CJEU ruling with green groups claiming it completely bans the use of neonicotinoids while others contest that interpretation.

The principle of allowing derogations for the use of a specific plant protection product at a Member State level stems from Article 53 of Regulation 1107/2009 which permits them for limited and controlled use, where such a measure appears necessary because of a danger which cannot be contained by other reasonable means. In allowing such derogations, authorities consider five tests that must be met, namely:

- There must be a danger

- There must be special circumstances which make it appropriate to derogate from the standard approach to authorizations

- The danger must not be capable of being contained by any other reasonable means

- An emergency authorization must appear necessary because of that danger, and

- An emergency authorization may allow only limited and controlled use of the plant protection product

Anti-pesticide and organic farming advocates claim the ruling carries very broad implications: Will this backfire?

The first to applaud the CJEU ruling were the anti-pesticide advocates and other groups actively promoting lower intensity agricultural production systems, notably in the organic sector.

But questions have emerged as to the meaning of the CJEU ruling and its implications for both conventional and organic farming. PAN claimed “…that all pesticide derogations must end, as none of them can be deemed a real emergency”. If the PAN interpretation is consistently applied by regulatory authorities, however, then a closer examination should be line for numerous and regular emergency derogations applied for, and obtained by, the organic sector for the use of various pesticides and other inputs that would otherwise not be permitted in organic agriculture.

The relevant EU organic regulations 2021/1165 and 2018/848 (part one of Annex II) requires pest and disease management to rely for protection from natural enemies, resistant varieties, crop rotation and thermal processes. Where plants cannot adequately be protected from pests by these measures or in the case of an established threat to a crop, an additional list of otherwise banned products can be used but ‘only to the extent necessary’.

The organic regulations provide for the use of emergency derogations to allow the use of some pesticides in circumstances very similar to those for non-organic production systems. These derogations allow for the use of various pesticides including sulphur, paraffin oil, spinosad, pyrethrins and copper-compounds (e.g., oxychloride, sulphate and Bordeaux mixture) to control blight, which are widely used in the growing of grapes, tomatoes, apples and potatoes organic potato crops. The synthetic insecticides deltamethrin and lambda cyhalothrin are allowed for use by organic farmers in pheromone traps.

Scientists have also confirmed that the organic insecticide spinosad, touted as an alternative to ‘dangerous synthetic pesticides by the industry, has been found to damage non-target insects far more than targeted synthetic insecticides.

Many of these products are not authorized for general use based on scientific concerns surrounding their safety and environmental impact. In January, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) concluded that exposure to copper traces in foods through compounds used in organic and conventional farming do not pose a serious health risk to consumers. However, EFSA has not changed its 2018 assessment that the potential accumulation in the soil of copper, a non-biodegradable heavy metal, is an ecological risk endangering farm workers, mammals, birds and soil organisms. The EU has, nonetheless, continued to grant derogations for the use of these products in the organic sector.

A recent impact assessment of the EU’s Green Deal Farm-to-Fork and Biodiversity Strategies by Wageningen University warned that switching to organic farming would have adverse consequences for meeting the EU targets for reduced use of pesticides, mainly due to the widespread use in organic crop production of copper-based active ingredients— which have been given a pass by regulators after lobbying by organic farmers despite known risks linked to their widespread use.

Will the organic industry double standard continue?

Will anti-pesticide advocacy groups be consistent with their stance against the emergency use of derogations for limited and controlled use of pesticides like neonicotinoid seed treatments in non-organic agriculture by extending the logic of the CJEU ruling to similar pesticide use derogations in the organic sector?

Given that the main EU organic regulation (Reg 2018/848) also provides for other derogations and exceptions for the use of non-organic inputs, reproductive materials (seeds or the animal-equivalent), feed materials, additives (food and feed) and processing aids in the production and manufactured of products certified as organic, then a consistent application of PAN’s interpretation of the CJEU ruling should mean that these regularly used organic derogations should end.

In the eyes of consumers, they are paying a price premium for organic food because it comes from a totally organic production system and this means from start to finish, from seed or birth to harvesting, finishing and sale. They are being misled by organic farmers asking for and receiving regular (annual) derogations for the use of non-organic seed or to use conventionally-reared youngstock.

Following the logic of the PAN’s interpretation of the CJEU ruling, the use of conventional seed and conventionally-reared youngstock for organic use should stop.

EU regulatory inconsistency

Returning to the broader issue, the foundation of this inconsistency largely stems from the move away from science and evidence-based risk regulation and policy making over the last 25-30 years. The European Union has moved to regulations and policy based on a poorly defined, hazard-based ‘precautionary principle’. There is increasing divergence between the regulatory approval mechanisms of the EU for pesticides, genetically modified crops and more recently gene edited crop and livestock innovations versus the equivalent regulatory authorities in major agricultural producing and trading countries in North and South America and Asia.

The fingerprint of the precautionary principle is evident in the EU neonicotinoids ban decision as illustrated by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA)’s Question and Answer briefing on its review findings of 2018 in which ‘information on the most likely way in which bees might be exposed to neonics is somewhat limited’. Regulators in other countries such as the US and Canada using globally accepted risk standards have determined, on the basis of science and evidence, that neonicotinoids, particularly seed costings, are safe for outdoor use.

In addition, in the UK, where pesticide approvals and derogations are also currently implemented under the same EU regulations operating in post Brexit UK law, the relevant authorities continue to allow emergency authorization based on evidence. In January 2023, the UK extended the derogation for use of one neonicotinoid product in sugar beet for the forthcoming 2023 growing season.

The inconsistency in the EU’s regulatory approach has been apparent in relation to the development of GM derived covid-19 vaccines. Politicians across Europe queued up to praise these medical breakthroughs and to re-assure citizens of the robust, science-based regulatory approval systems in place to ensure their safety as the vaccines were fast-tracked through the approval process and into deployment.

Yet these vaccines use the same techniques of genetic modification (GM) or gene editing (GE) that many of the same politicians have spent the last 25 years preventing their citizens and farmers from accessing for the production and consumption of food, feed and fiber crops. That’s a non-science and non-evidence-based approval approach to these products.

Persisting with policy and regulation systems based on the poorly defined precautionary principle, which is open to variable interpretation and the application of non science and evidenced based influences, is a recipe for inconsistency and failure. If the EU wants its agricultural production sector to actively contribute and transition to a more sustainable future, its regulations and policies need to be consistently based on science and evidence.

Graham Brookes, agricultural economist with PG Economics, UK, has more than 30 years’ experience of analyzing the impact of technology use and policy change in agriculture. He has authored many papers in peer reviewed journals on the impact of regulation, policy change and GM crop technology. www.pgeconomics.co.uk