“Much remains unknown, but this is certainly cause for concern and follow-up study,” said Philip Demokritou, the Henry Rutgers Chair and professor in nanoscience and environmental bioengineering at the Rutgers School of Public Health.

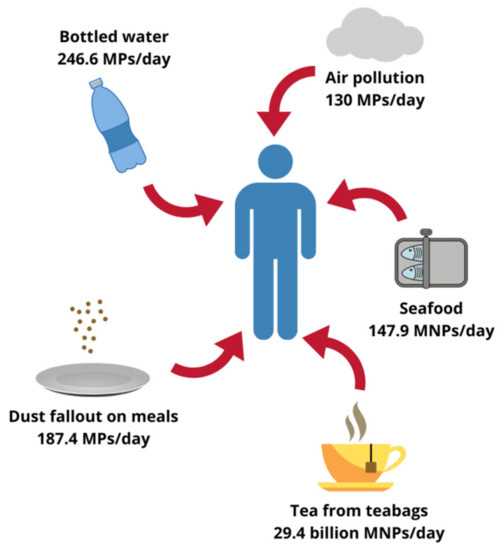

Erosion causes microscopic plastic particles to break away from the billions of tons of plastics in the environment that are exposed to the elements. These particles mix with our food and air, with an average person ingesting the equivalent amount as a credit card each week, according to Demokritou.

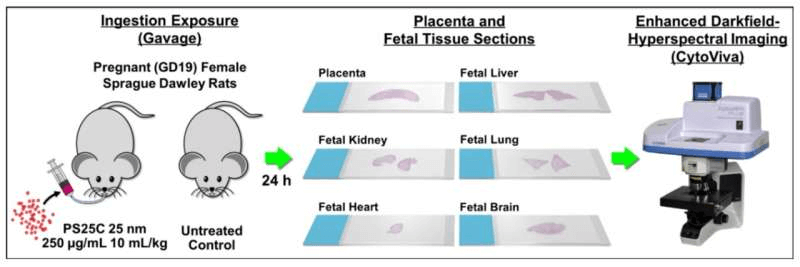

Previous studies in pregnant laboratory animals have found adding these plastics to food impairs their offspring in numerous ways, but those studies didn’t determine whether mothers passed the plastics to their children in utero.

The study provided specially marked nanoscale plastics to five pregnant rats. Subsequent imaging found that these nanoplastic particles permeated not only their placentas but also the livers, kidneys, hearts, lungs, and brains of their offspring.

These findings demonstrate that ingested nanoscale polystyrene plastics can breach the intestinal barrier of pregnant mammals, the maternal-fetal barrier of the placenta, and all fetal tissues. Future studies will investigate how different types of plastics cross cell barriers, how plastic particle size affects the process, and how plastics harm fetal development, the researchers said.

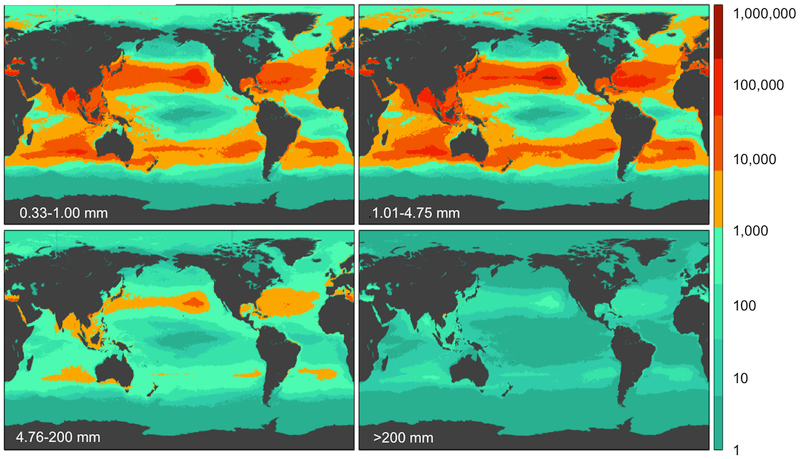

“The use of plastics has exploded since the 1940s due to their low cost and versatile properties. From 9 billion metric tons produced over the last 60 years, 80 percent ended up in the environment, and only 10 percent were recycled,” said Demokritou, who also holds appointments at Rutgers’ School of Engineering and directs the Nanoscience and Advanced Materials Research Center at the Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences Institute.

“Petroleum-based plastics are not biodegradable, but weathering and photooxidation break them into tiny fragments. These tiny fragments, called micro-nano-plastics, are found in human lungs, placentas, and blood, raising human health concerns. As public health researchers, we are trying to assess the health risks from such an emerging contaminant to inform policymakers and develop mitigation strategies. The goal is also to increase the reuse and recycling of plastics and even replace them with biodegradable, biopolymer-based plastics. This is part of our bigger societal goal towards sustainability.”

Feeding pregnant lab animals nanoscale plastics — a nanometer is one billionth of a meter, so the particles are far too small to be seen — has been shown to restrict the growth of their offspring and to harm the development of their brains, livers, testicles, immune systems, and metabolisms.

It hasn’t been shown yet that the amounts of nanoscale plastics that pregnant humans unavoidably ingest do the same thing to their children, though some studies suggest plastics affect human embryonic development, Demokritou said.

Andrew Smith is the Senior Public Relations Specialist at Rutgers University.

A version of this article was originally posted at Rutgers University and has been reposted here with permission. Any reposting should credit the original author and provide links to both the GLP and the original article. Find Rutgers on Twitter @RutgersU