One of the biggest challenges facing farmers today are so-called “superweeds” — the popular term for weeds that have developed resistance to herbicides and are difficult to control. They were first observed decades ago as weeds adapted to survive the chemical herbicides that farmers used to boost yields.

More recently, anti-GMO activists have tried to blame the problem specifically on glyphosate, the active ingredient in Monsanto’s Roundup herbicide, which is used in conjunction with many herbicide resistant GMOs. Here is a recent post by GMO Inside, a group that supports labeling and a “right to know” but is also campaigning to get GMOs banned:

The strategy of combating weeds by engineering crops that can withstand herbicides and then blasting fields with those chemicals is no match for evolutionary adaptation, as demonstrated by the rapid growth of superweeds across the country. … There is no question that GE technology will continue to drive up the costs of food production, increase the use of harmful chemicals and undermine efforts for a sustainable food system.

This cause has been adopted by the Union of Concerned Scientists, which blames Monsanto and glyphosate for perpetuating what mainstream agricultural experts calls the Green Revolution, which has increased yields multi-fold in 60 years saving hundreds of millions of lives, but which the advocacy group derisively calls “industrial agriculture“–chemically intensive food production developed in the decades after World War II, featuring enormous single-crop farms and animal production facilities.

Last week, the UCS released a video that presents its view as to how Monsanto “supersized” farmers’ weeds problem with its Roundup Ready system. The UCS produced the video to promote a policy brief by Doug Gurian-Sherman and Margaret Mellon, UCS senior scientists in the Food and Agriculture program, and established GMO skeptics. It first paints weeds as “super villains,” stealing water, light and nutrients from crops, and Monsanto’s Roundup seeds and herbicide as “superheroes” fighting off weeds, but then the story turns darker:

The video is uncompromising in its critique of Monsanto and what it believes is the agribusiness takeover over global farming:

Roundup Ready seemed like a superhero. But this superhero had a fatal weakness: resistance. Some weeds have genes that protect them from Roundup’s effects, and the more Roundup farmers used, the quicker the resistance genes spread over time. Encouraged by Monsanto’s marketing campaigns, farmers used so much Roundup that resistance soon accelerated into a superweed crisis. Millions of US farm acres are now infested with superweeds. Instead of solving the farmers’ problems, Monsanto has supersized it.

“It sounds like a bad sci-fi movie or something out of The Twilight Zone. But ‘superweeds’ are real and they’re infesting America’s croplands,” said Gurian-Sherman in the press release that accompanied the release of the video. “Overuse of Monsanto’s ‘Roundup Ready’ seeds and herbicides in our industrial farming system is largely to blame. And if we’re not careful, the industry’s proposed ‘solutions’ could make this epidemic much worse.”

The UCS casts agricultural biotechnology and industrial farming as the culprit for creating the superweed problem. The core of industrial farming, they claim, is monoculture farming, the practice of growing only one crop intensively on a very large scale every year. In the United States, corn, soy, cotton and wheat are often grown this way, although that system has begun to change in recent years in part because of the development of hardier weeds.

Pests like weeds and insects affect crops selectively, so when farmers grow different crops each year, a practice called crop rotation, they disrupt the pests’ sources of food and nutrients, and prevent them from adapting.

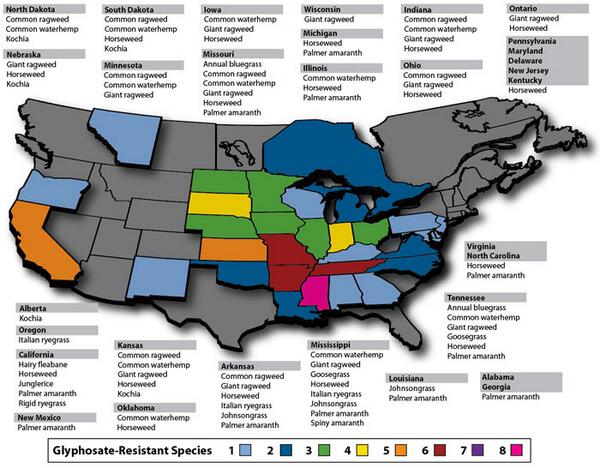

In monoculture, the pests are only controlled by chemical means, and since the same crops are planted year after year, the pests are able to quickly adapt and evolve to survive. Herbicide-resistant weeds have become a major challenge, appearing in an estimated 60 million acres of farmland. The map below illustrates the area affected by glyphosate-resistant weeds in the United States:

Are Roundup Ready crops to blame for “superweeds”, as UCS and anti-GMO activists contend? Herbicide resistance in weeds developed long before the adoption of herbicide-resistant GM crops. Andrew Kniss, professor of weed biology and ecology at the University of Wyoming observed that the first glyphosate-resistant weeds “evolved in Australia, where no GM crops were grown” back in 1996. GM crops played no role in their development.

Weed resistance developed because of the way glyphosate was used in tandem with monoculture farming by some farmers looking for shortcuts. “Glyphosate-resistant weeds evolved due to glyphosate use, not directly due to GM crops,” wrote Kniss. Some farmers found it easier to simply plant the same crops and control weeds with a single herbicide, glyphosate, year after year.

The UCS has criticized Monsanto for what the advocacy group says is the company’s aggressive marketing campaigns that encourages farmers to become over-reliant on Roundup and neglect other weed-controlling techniques. Food writer Nathanael Johnson came to a similar conclusion in his series on GMOs for Grist:

Spraying glyphosate in conjunction with GM herbicide-tolerant crops was so easy and effective that agronomists started referring to it as “agricultural heroin.” It worked so much better than anything else that farmers became addicted.

To address what they believe is the real issues behind superweeds, Gurian-Sherman and Mellon’s policy brief hones in on three factors:

Monoculture. Growing the same crop on the same land year after year helps weeds to flourish.

Over reliance on a single herbicide. When farmers use Roundup exclusively, resistance develops more quickly.

Neglect of other weed control measures. The convenience of the Roundup Ready system encouraged farmers to abandon a range of practices that had been part of their weed control strategy.

Gurian-Sherman and Mellon recommend a shift away from herbicides and GM crops towards practices like crop rotation, which in fact is now more widely used by conventional farmers, and cover crops. They reject the new generation of herbicide-resistant crops awaiting approval from the USDA and EPA, contending that more herbicide-resistant weeds will eventually appear and some might even become resistant to multiple herbicides.

“Fighting fire with fire will only result in a conflagration – farmers deserve solutions that will not fail in a few years, and land them in an even deeper hole,” said Gurian-Sherman. “Instead of favoring the same industrial methods and genetically engineered products that got farmers into this mess, public policies should promote healthy farming practices that can produce long-term benefits for American farmers, consumers, and the natural resources we all depend upon.”

As an alternative to “industrial agriculture”, Gurian-Sherman and Mellon advocate for “agroecological” practices that look a lot like organic agriculture, using only “crop rotation, cover crops, judicious tillage, the use of manure and compost instead of synthetic fertilizers, and taking advantage of the weed-suppressing chemicals that some crops produce,” according to the policy brief.

Adding practices like crop rotation to address the problems of monoculture is not new; more and more conventional farmers are adopting a combination of ecological techniques called integrated pest management (IPM) to prevent superweeds and other excesses linked to conventional methods. But most ecologists and farming experts contend that removing chemical weed-control options from farmers, including limiting biotechnology, and returning to organic agriculture is too simplistic; multiple tools are needed to control weeds effectively without burdening farmers. Anthony Shelton, Cornell University professor with the department of entomology, wrote:

Even more than organic production, IPM strives to use the best scientific practices to ensure safe and sustainable agricultural systems. To do this, IPM incorporates practices from conventional and organic production methods, and even biotechnology, a method that has been turned into a bogeyman, but in reality is safer for humans and the environment. IPM has been a national policy for the United States since 1993 and its implementation has resulted in dramatic decreases in the use of harmful pesticides.

Additional Resources:

- “Targeting weeds at the genetic level,” Genetic Literacy Project

- “Can GM crops really pass their benefits to weeds?” Weed Control Freaks

- “No Herbicides & Pesticides – No problem: 70 Million “New” Jobs Created to Grow Our Food,” Truth About Trade & Technology