Science has a long history of self-experimentation. Pierre Curie famously burned himself with radioactive salts to the effects of radiation. The inventors of spinal anesthesia and LSD also took their experiments out for a ride themselves during development. And now Jess Leach, and anthropologist, infectious disease student and co-founder of the World Food Project has followed in these illustrious foot steps. Leach gave himself a fecal transplant.

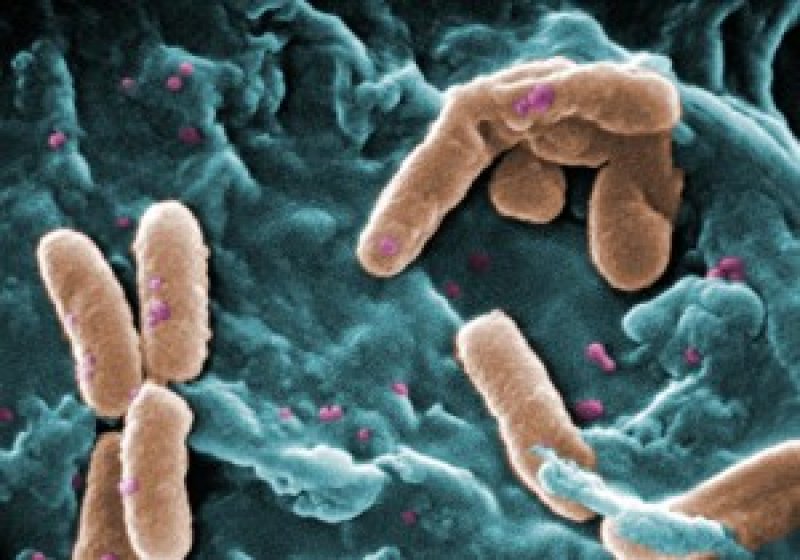

Leach studies the microbiomes, the collection of bacteria in our guts, mouths and on our skin, from populations that have not adopted the highly processed diets of the developed world. These folks still eat, for the most part, what their ancestors ate. Leach’s research has shown some interesting results. Hadza gut microbiomes change seasonally, with the the wet and dry seasons. And the Hadza gut didn’t contain the bifidobacterium and lactobacillus bacteria that commonly included in probiotic products throughout the Western world.

But jumping from studying a population’s microbiome to suggesting that you adopt it is quite a leap. Leach said all of the experts he talked to about the plan urged him not to do it, for his own safety. As John Hawks writes, “Many people around the world carry potentially harmful parasites, from tapeworms to treponema. Shooting these up your anus is a bad idea.”

Leach didn’t have data on his donor’s parasite status, but he went for it anyway. He did not develop a parasite, lost a few pounds and reportedly has less gas as attested by his girlfriend. His bacterial cultures did shift, although how long that shift remains in place after his return to the develop world might be a more interesting question.

But there are other questions to be asked here. First of all, Leach had been living in undeveloped parts of Africa for a long time at this point, far from the closest MacDonald’s or Whole Foods or Tesco. And subsequently, far from his traditional diet. His microbiome may already have been changed by adopting the Hadza diet.

Secondly, people’s microbiomes evolved based on where they lived, what they ate, what disease they faced and what their genetics were. One size does not fit all, Hawks explained:

Hadza have their own long evolutionary history. Their diet is merely one representative of the marked dietary diversity of recent hunter-gatherers. Other foraging groups, for example, the Ache of Paraguay, have a very different dietary composition. The study of these microbiomes is scientifically very interesting, and we may discover commonalities among them. But the idea that the microbiome of any Hadza person represents an “ancestral” or “healthy” human population is nonsense. They have their own distinctive set of challenges affecting their microbiomes, including the aforementioned parasites. A microbial community that has formed within a Hadza gut might work equally well anywhere else, but there’s really no reason to expect that it will.

Furthermore, there is evidence that when your microbiome and your genetic lineage don’t match, bad things can happen… like cancer.

Lastly, there is the issue of exploitation. Presumably, this fecal donor was willing and proper consent was given. Leach described him as a friend. But fecal mining of hunter gathers is not that different than mining their lands for other resources: it’s exploitation of a natural resource.

While Leach’s experiment makes for a great story, we should be wary about adopting this line of scientific investigation. It’s too early to know what a fecal transfer like this means, if its safe and if it can be ethically done.

Meredith Knight is editor of the human genetics section for Genetic Literacy Project and a freelance science and health writer in Austin, Texas. Follow her @meremereknight.

Additional Resources:

- Developing new antibiotics from human microbiome, Economist

- Your microbiome isn’t just in you: It’s all around you, National Geographic

- What can our microbiomes tell us about ourselves?, National Geographic