Just over a week before Vermont’s ‘first in the nation’ GMO labeling law is set to go into effect, a bipartisan agreement has been reached in the U.S. Senate to try and tackle the issue.

The accord, reached by Senate Agriculture Chairman Republican Pat Roberts and Senator Debbie Stabenow, the committee’s ranking Democrat, would require labeling but allow companies to disclose GMO ingredients on packages via digital codes. The bill would create a national standard for labeling such foods and would pre-empt other states from making their own laws. But activists have already sharply criticized the bill and its Senate authors.

The standard agreed upon would give most food companies the option of disclosing genetically engineered ingredients through different options, including a digital or smartphone code, a symbol on the package or language approved by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Smaller food companies would be able to put a phone number or website on their label instead of the code, while “very small” food producers will be exempt entirely.

The bill also sets a very narrow definition of what is and what is not a GMO and would allow products certified as organic by the USDA to add “non-GMO” to their label. The latter is a provision the organic industry has long sought and could put in jeopardy the Non-GMO Project, a non-profit that for a fee will certify products as non-GMO.

“We saved agricultural biotechnology,” Roberts said after announcing the compromise. Stabenow called the bill a win for families, consumers and farmers:

Throughout this process I worked to ensure that any agreement would recognize the scientific consensus that biotechnology is safe, while also making sure consumers have the right to know what is in their food. I also wanted a bill that prevents a confusing patchwork of 50 different rules in each state. This bill achieved all of those goals, and most importantly recognizes that consumers want more information about the foods they buy.

Many in the food manufacturing and biotech worlds were supportive of the compromise. Pamela Bailey, president and CEO of the Grocery Manufacturers Association said, “this bipartisan agreement ensures consumers across the nation can get clear, consistent information about their food and beverage ingredients and prevents a patchwork of confusing and costly state labeling laws.”

The Organic Trade Association also supported the bill. “This legislation includes provisions that are excellent for organic farmers and food makers — and for the millions of consumers who choose organic every day — because they recognize, unequivocally, that USDA Certified Organic products qualify for non-GMO claims in the market place,” it said.

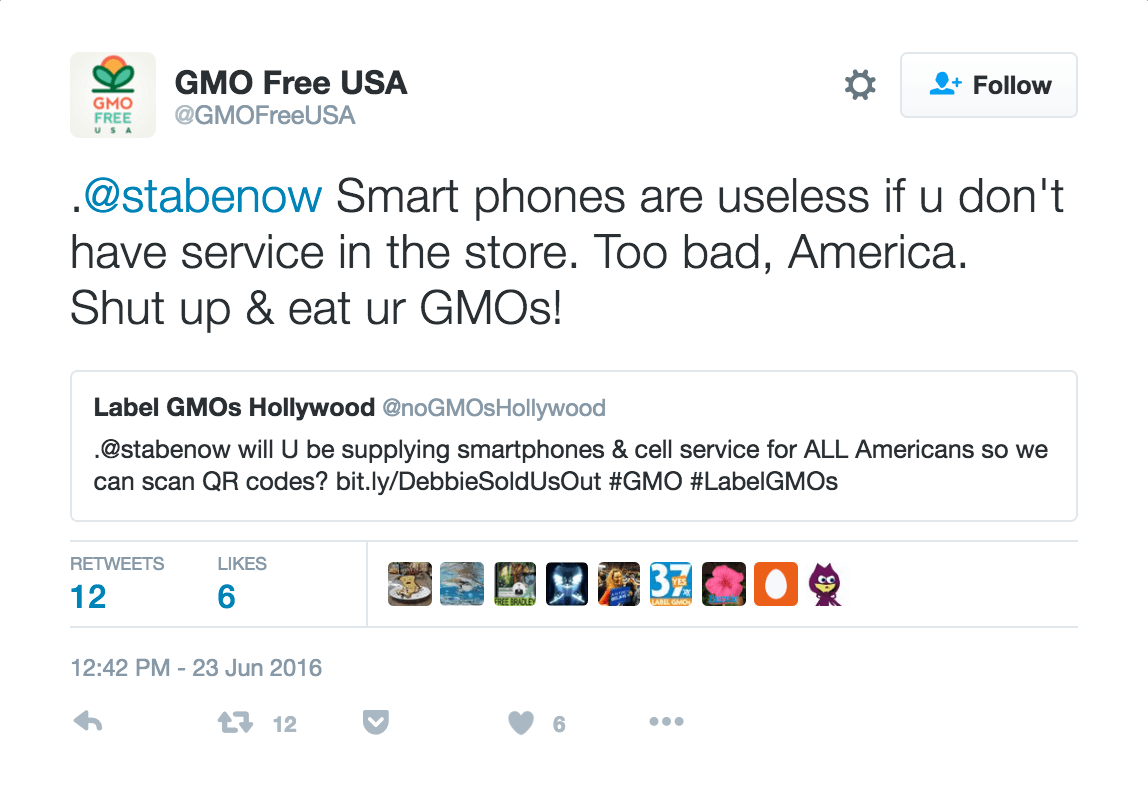

Despite support from the organic industry’s largest trade group, many activists and organic industry food leaders criticized the bill. Gary Hirshberg, chairman of Just Label It and Stonyfield Farm, was pleased GMO labels would be nationally mandated and that the compromise would lead to more products being labeled than Vermont’s law. However, he and others criticized the provision that would allow manufacturers to have the option of labeling their products via scan codes instead of on on the package.

[W]e are disappointed that the proposal will require many consumers to rely on smart-phones to learn basic information about their food….This proposal falls short of what consumers rightly expect — a simple at-a-glance disclosure on the package.

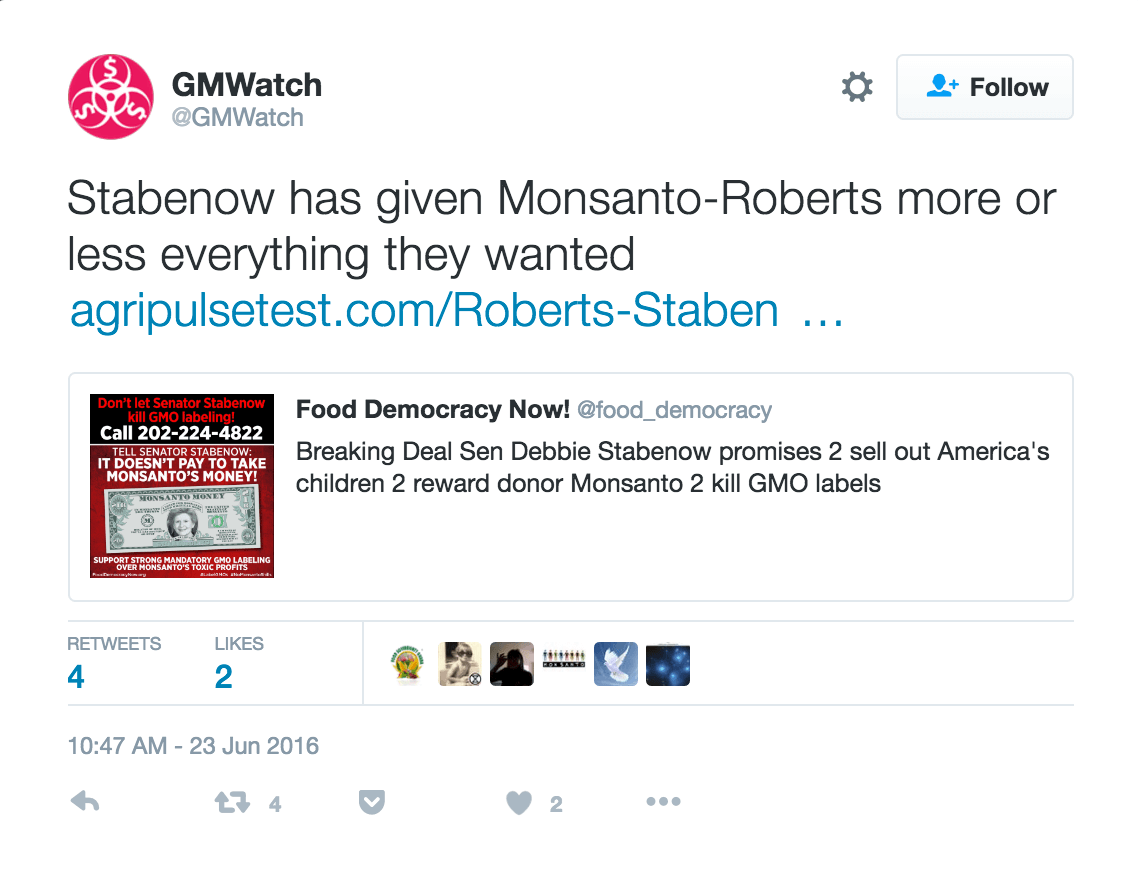

Several anti-GMO groups also took to social media to display their displeasure:

Carey Gillam, research director for U.S. Right to Know, said the proposed bill will “will continue to leave consumers largely in the dark about the GMO content of their groceries.”

Andrew Kimbrell, executive director of the Centers for Food safety, who has referred to previous bill proposals from Roberts as “unconstitutional” and “discriminatory”, called the current bipartisan one “a non-labeling bill,” adding he was, “appalled that our elected officials would support keeping Americans in the dark about what is in our food and even more appalled that they would do it on behalf of Big Chemical and food corporations.”

What happens next?

Under the proposed bill, genetic engineering is defined as those traits created via recombinant DNA techniques which move genes between organisms—the use of so-called “foreign” genes. The federal version specifically exempts newer breeding techniques such as gene editing (like CRISPR) and RNA interference. This definition is narrower than Vermont’s bill. The USDA had already announced it would not regulate a mushroom made via CRISPR. The bill also states that meat and dairy products cannot be labeled as GMO solely on the grounds that the animals consumed GMO feed.

The USDA issued a statement in support of the compromise agreement:

“It is our hope that their colleagues in the Senate and House of Representatives recognize the difficulty of their work, and the importance of creating a path forward. The most impressive outcome of their agreement is that this measure encompasses over 24,000 more products than the Vermont law, which should assure people that this measure can be transparent without sending the wrong message about the safety of their food options.”

The USDA’s Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS) would be required to finalize rules laying out requirements including texts and symbols. The marketing service would be given two years to complete the task at which point the bill would go into effect. While much of the bill’s implementation will be done by the USDA, the agency will not have the power to enforce some of its provisions. It cannot require recalls of products that do not comply and it cannot issue penalties or fines for violations, instead that power is given to the states.

The compromise between two key, often opposing, players in the labeling debate increases the likelihood that the overall Senate will approve of it, but does not seal the deal. It will need the backing of 60 Senators before proceeding to block the potential for filibuster. In March, a committee-passed bill failed in the Senate, falling 12 votes short of the required minimum of 60. Nor will this bill will be enacted before Vermont’s labeling law goes into affect on July 1; it is unlikely the bill will be brought up for debate for another month though.

If the Senate pass the bill, the House will have to approve it for it to move forward because it is much different than a version passed in House in July 2015 by a 275-150 margin. The two bills have significant differences–the House bill provided voluntary labeling for example. If passed, the bill would then need the signature of the president.

It is unclear how long this process will take as both chambers of congress are on break for the holiday and party conventions. It is also unclear at this point how effective criticism from crop biotechnology critics will be in derailing the bill. Many of them are committed to legislation, at the state or national level, that stigmatizes genetically engineered products with prominent package labels.

Previous bills have failed to garner significant bipartisan support in the Senate, but the role of Stabenow, a Democrat and organic food supporter, as primary negotiator could help garner more support for the bill among skeptical Democrats.

Nicholas Staropoli is the associate director of GLP and director of the Epigenetics Literacy Project. He has an M.A. in biology from DePaul University and a B.S. in biomedical sciences from Marist College. Follow him on twitter @NickfrmBoston.