Over the past two months, many in the media and the science community have been spinning a new ‘birds and bees’ story: they are deathly threatened by crop protection chemicals. Like the original, it’s an awkward story, but in a different kind of way, because, for the most part, it’s embarrassingly wrong.

Let’s talk about the bees first. Going back more than a decade now, there have been literally thousands of reports, amplified by the media, claiming that honeybees are in danger of extinction due to the use of crop pesticides (here, here, here). The reason? Reports based on mostly small-scale laboratory studies finger a primary culprit: One class of insecticides, neonicotinoids.

What are neonicotinoids?

Since the mid-1990s, neonics, as they are often called, have largely replaced pyrethrin and organophosphate pesticides, which had been found to kill beneficial insects, threaten wildlife and pose health problems to humans. Neonics pose none of those threats. Used mainly as  treatments on corn and soybean seeds, they are absorbed into the plant, targeting crop-destroying pests while minimizing exposure of beneficial species.

treatments on corn and soybean seeds, they are absorbed into the plant, targeting crop-destroying pests while minimizing exposure of beneficial species.

The introduction of neonics turned out to be opportune for farmers and honeybees. Beginning in the mid 1980s, farmers across the world that used European honeybees (the most common ‘livestock bee’ around the world outside of Asia, including in the United States), began seeing a dramatic invasion of a Japanese parasite called the varroa destructor. According to the latest theory, the mites feed on the fat from adult bees and the developing brood, and while they do not immediately kill, they literally suck the life out of them over time. They reduce bees’ immune system, making them more susceptible to environmental factors such as extreme cold or crop chemicals that do not harm healthy bees. Varrora is also a vector for at least five debilitating diseases, including RNA viruses such as the deformed wing virus (DWV).

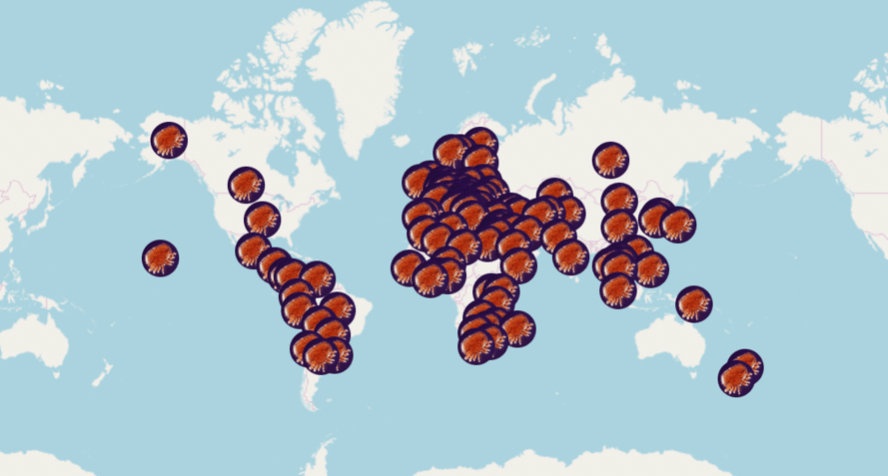

By the 2000s, the deadly infestation had missed only Australia, northern Canada and parts of northern Sweden and Norway. (Asian bees, a different species, had long ago developed an immunity to the blood sucker.)

Global interactive map shows spread of varrora since 1908. http://wblomst.com/varroa/

Within a few years after the introduction of neonicotinoid seed treatments, they were celebrated almost as a miracle insecticide as they reduced the overall toxicity of pesticide use and had few if any documentable impacts on non-target species. With their rapid embrace by farmers around the world, the global honeybee population stabilized even as the varroa infestation escalated.

What caused CCD? Not crop chemicals

Then crisis struck. Beginning in 2006, honeybees began dying off in California and nearby states in record numbers, an unexplained—what scientists said was an almost spontaneous phenomenon, dubbed Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD).

Environmental activists are not always known for their understanding of scientific nuance; however, they are often very adept at exploiting  complicated crises, shaping a easily digestible explanatory narrative to promote policies that they believe (sometimes wrongly) further their ideological objectives. Within weeks of reports of the CCD crisis, many anti-GMO organizations started blaming GMO crops (e.g. “Death of the Bees. Genetically Modified Crops and the Decline of Bee Colonies in North America”), which of course proved farcically untrue.

complicated crises, shaping a easily digestible explanatory narrative to promote policies that they believe (sometimes wrongly) further their ideological objectives. Within weeks of reports of the CCD crisis, many anti-GMO organizations started blaming GMO crops (e.g. “Death of the Bees. Genetically Modified Crops and the Decline of Bee Colonies in North America”), which of course proved farcically untrue.

What causes CCD? It still remains a mystery, in part. But researchers turned up historical examples of CCD-like bee die offs across the globe over hundreds of years, well before the introduction of pesticides, but activist groups would have none of it.

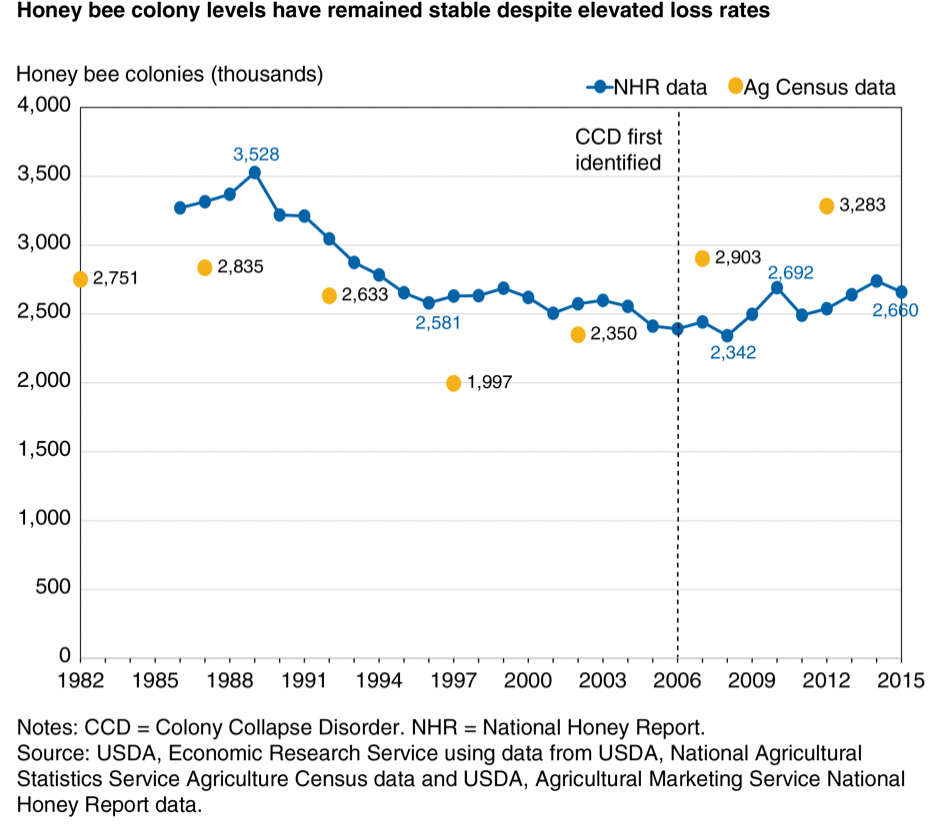

By 2009, CCD was abating and the honeybee population growing again (as the chart of the US hive population above illustrates). But the bee health crisis remained in the news, as a rare series of stingingly cold winters in North America and Europe took a toll on the insects, even as the recovery from CCD gathered steam.

After the collapse of the anti-GMO narrative, activists aimed their fire at pesticides, neonics in particular, as they are prominently used on crops that utilize bees for pollination. In contrast, most entomologists blamed a complex combination of factors, including shifting habitats (such as urbanization), climate-change induced colder winters, the hauling of pollinating bees in trucks and the fact that North American and European honeybees have been weakened for years by the varrora destructor mite. Pesticides ranked near the bottom of the list, ’11 out of 10,’ said one prominent entomologist.

They also note that data from one of the countries that used the most amount of insecticides per acre—Australia—completely undermines the ‘neonic-kills-bees’ narrative. Australia is a real-world laboratory for these claims. It fortuitously has avoided the varrora infestation and its honeybee population is robust.

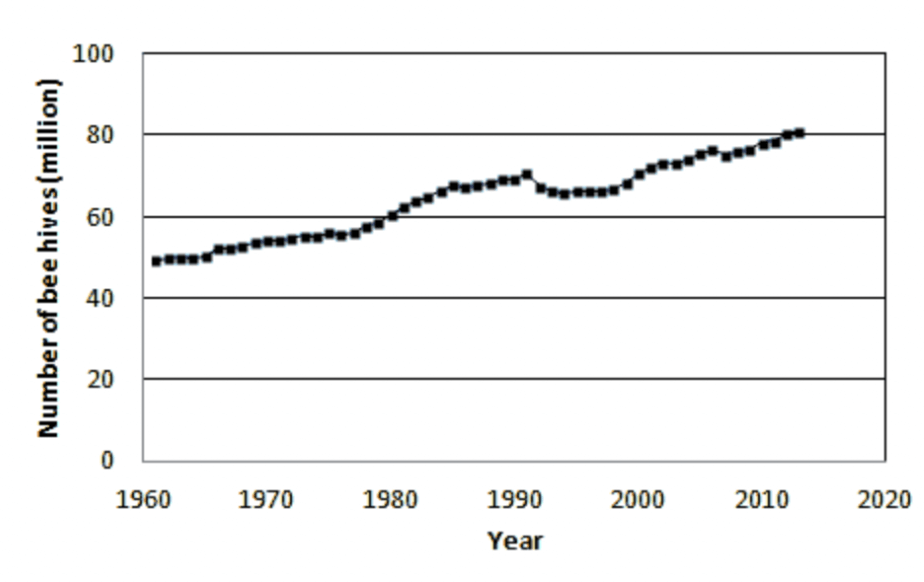

The introduction of neonics actually coincided with increased farm production, and a steadily increasing, extremely healthy honeybee population, up almost one third since the debut of the chemical. As the Australian parliament documents on its website, “[I]n Australia, honey bee populations are not in decline and insecticides are not a highly significant issue.”

Source: Australian Department of Agriculture, 2019

The emergence of the deadly neonics’ narrative and the Australian case study

Despite a slight dip in numbers for a few years during the CCD crisis, honeybee colonies in the US quickly recovered and since 2011 have shown remarkable stability, even chalking up significant gains fr om pre-neonic levels.

om pre-neonic levels.

But advocacy groups, with their crisis narrative amped by an aggressive group of scientists known for their environmental activism (e.g. see UK biology professor David Goulson as a prime example), would have none of it. They eschewed a nuanced discussion about bee health, spurring a tsunami of hysteria-driven news reports that rarely conveyed the contextualized science, especially in addressing a crisis as deeply complex as bee health.

By 2012, the media was just getting started in what became almost a daily surge of apocalyptic reports that has continued ever since. As I have pointed out consistently in my reporting, since confirmed by the Washington Post, Slate and almost every major science publication, we are not facing a ‘world without bees’—the misleading Time magazine 2012 cover story aside.

What terrible reporting. The number of beehives worldwide has been rising almost continuously for the past 50 years, according to FAOSTAT. There are now nearly 22 million more beehives in the world than in 2000–an increase of 31%.

What do the studies show?

Over the past seven years, there have been a flood of studies about the potential impact of neonics on bees. Many small-scale, forced-feeding studies that generally overdosed bees with neonics found various negative effects; not a surprise, many entomologists have said, as they do not replicate real world impacts.

In contrast, a multitude of large-population field studies—the “gold-standard” of bee research—have consistently demonstrated there are no serious adverse effects of neonic insecticides on honeybees at the colony level from field-realistic neonic exposure.

Numerous news organizations have more recently carried activist claims that data suggesting increases in over-winter deaths show that  honeybees are being mortally weakened by chemicals. On average over the past 13 years since the CCD crisis, about 29 percent of honeybee colonies in the US have died each winter (e.g. here is NPR reporting just last winter that a “record number of honeybee colonies died”; here is the New York Times reporting a “worrisome…sharp spike in honeybee deaths.”)

honeybees are being mortally weakened by chemicals. On average over the past 13 years since the CCD crisis, about 29 percent of honeybee colonies in the US have died each winter (e.g. here is NPR reporting just last winter that a “record number of honeybee colonies died”; here is the New York Times reporting a “worrisome…sharp spike in honeybee deaths.”)

Is that yet another pesticide-induced crisis? Not when you look at data trendlines. As the GLP recently reported, a long-term study by Wageningen University in the Netherlands documents that “the period of alarmingly high winter mortality in honeybees is over”—and has been since 2012, about when the misreporting started. It’s gone down by half since after the brief upsurge in 2006-2011, which was linked to brutal winters and the lingering effects of CCD, which has no connection to pesticide use.

This is not to say that the bee population is without serious threats. But as I have documented for years on the GLP, the global honeybee population had stabilized by the mid-1990s when neonics were first introduced and have been steady or rising on every continent in the world (except Antarctica) ever since, even as neonics gained in popularity among farmers and became the most widely used class of insecticides.

By last year, even the Sierra Club—for years one of the leading proponents of the honeybee Armageddon narrative—was backpeddling, writing:

Honeybees are at no risk of dying off. While diseases, parasites and other threats are certainly real problems for beekeepers, the total number of managed honeybees worldwide has risen 45% over the last half century.

Almost as soon as the ink was dry on its retreat from the honeybee crisis narrative, the Sierra Club and other activists refocused on wild bees. Without irony, the Sierra Club headlined its shameless 2018 pivot, “How the Honeybee Buzz Hurts Wild Bees.” [Editor’s note: The SC relentlessly has promoted the honeybee crisis for more than 6 years before finally aligning itself with mainstream science].

What science is their new claim based on? None, really, as the GLP has previously reported, because there is so little credible data to assess speculative claims about wild bee health. The foremost authority of wild bees in the US, Sam Droege, of the US Geological Survey, has challenged the wild bee crisis narrative, insisting that wild bee populations are generally healthy. Agricultural practices likely has had little to do with whatever problems they might be facing, he has said. This is because most wild bees live far from farmland and those few species that do pollinate crops are fl ourishing.

ourishing.

The trope that crop chemicals are endangering [fill-in-the-blank environmental issue] has a firm grip on the media. In a since-widely ridiculed article The New York Times Magazine cover story in 2018, “The Insect Apocalypse is Here,” falsely claimed that all insects, bees included, face extinction.

Birds enter the crisis narrative

Far from discouraging the anti-pesticide activists, however, these bungled narratives have only led to even more stories about impending environmental catastrophes, mostly ascribed to neonics in a seemingly never-ending effort to get them banned. This is where ‘birds’ come in.

In late September, the scientific team of Margaret Eng, Bridget Stutchbery and Christy Morrissey (Eng and Morrissey are at the University of Saskatchewan; Stutchbury is at York University) published a much-reported study that claimed neonics posed a threat to North American bird populations.

Here is how the study was carried out. The Canadian team captured White-Crowned Sparrows at a bird sanctuary on the north shore of Lake Erie. Were birds to be affected by neonics in the wild, it would be by munching on the occasional coated seed left above ground when farmers sow their fields. Not these laboratory birds. As in the bee studies, these birds were force fed pesticides via gavage.

Not familiar with the term? The researchers stuck a tube down the birds’ throats and force-fed the mixture into their stomachs—which was likely necessary as birds in the wild generally avoid feeding on neonic-treated seeds.

Birds in the control group received no neonic pesticide while the remaining two groups were force-fed either a medium (1.2mg/kg of body weight) or high (3.9 mg/kg) dose of Imidacloprid, the first and oldest neonic pesticide commercialized. After dosing, the birds were released with tracking devices for study.

What happened? Only sparrows force-fed the highest dosage were affected, and then only temporarily. They stopped eating, quickly lost body weight and fat, became disoriented and paused their migratory flight—all after tube full of chemicals was forced down their throat and into their stomach.

That said, within a few days of what was likely a trauma-inducing experience, all recovered completely and continued their migration normally. From this the authors conclude that all neonics post a threat to bird life. Their study claimed that the insecticides caused the birds to prolong their ‘refueling stops’, delaying their migration by days, which they hypothesized might be enough to mortally expose them to approaching winter weather.

Doomsday researchers manipulate the media

Why did this scientifically thin study become a favorite of activist campaigners and the media? Mostly, because the Eng team’s questionable  extrapolations dovetailed with an early October report, headlined “Staggering decline of bird populations,” finding that North American bird populations were in serious decline, a 29 percent drop since 1970. Its release, suggests the MIT-based science media site Undark, was orchestrated to create maximum media hysteria. Reporters parroted the news releases with almost no critical analysis.

extrapolations dovetailed with an early October report, headlined “Staggering decline of bird populations,” finding that North American bird populations were in serious decline, a 29 percent drop since 1970. Its release, suggests the MIT-based science media site Undark, was orchestrated to create maximum media hysteria. Reporters parroted the news releases with almost no critical analysis.

Ahead of the study’s publication, partners to the research registered the web domain 3 billionbirds.org to help get the

word out. … The study also came with its own hashtag, #BringBirdsBac“Where Have All the Birds Gone?” the Seattle Times asked. A piece in Vox wondered whether the trend would end in a “bird apocalypse.” (Not necessarily, the piece conceded.) And the headline on a front-page story in the New York Times declared that “Birds Are Vanishing From North America.” The dramatic opening line of the piece: “The skies are emptying out.”

Researchers affiliated with the Cornell team even managed to land an accompanying op-ed essay in The Times the very same day. “The Crisis for Birds,” the headline opined, “Is a Crisis for Us All.”

The facts receded and the activist-media noise escalated, with the hyped Cornell paper boosting renewed interest in the Saskatchewan study. As evidence showed, however, both the Eng team and the Cornell paper were wrong—about many things. First, the researchers focused on the wrong neonic pesticide. Imidacloprid is generally not used on corn, and soybean seeds are relatively unattractive to birds. The actual neonics that are widely used on corn and canola—clothianidin and thiamethoxam—are tens of times less toxic to birds, to the point that no sparrow could realistically ingest enough seeds treated with those neonics to receive a lethal or harmful dose.

To illustrate the difference in avian toxicity of these various pesticides, one summary of other research on larger bird species – rock pigeons and grey partridge—found that it would require ingesting 120 or more clothianidin-treated corn seeds or 160 or more thiamethoxam-treated corn seeds for the birds to receive the same pesticide exposure as found in 10 to 11 imidacloprid-treated corn seeds. These are volumes of seeds that are implausible for these larger birds, much less sparrows, to be able to consume.

For crops such as wheat, which are treated with imidacloprid, the birds’ de-husking instinct to get at the kernel eliminates much of the neonic seed-coating, avoiding ingestion and serious exposure. In any case, most wheat is planted later in the summer, which doesn’t coincide with the bird’s Spring migration, so it could hardly affect it.

But this was only one of several serious problems with the Eng-led study. Among others, they failed to note that birds rarely forage for food in newly planted cropland, bare as it is, because it is also barren of other food resources they seek. That is why the researches didn’t actually capture their study birds in agricultural fields. They captured them at the Long Point Bird Observatory in Ontario, a forested area known as a popular refueling stop on birds’ long season migrations.

Numerous reputable reputable news organizations reviewed the ‘bird crisis’ claims and found them exaggerated at the least. Noting the deceptive marketing campaigns, Slate headlined its article, “There is No Impending Bird Apocalypse.” Brian McGill, a macro ecologist at the University of Maine, who is writing his own analysis of the ‘bird crisis, wrote in Dynamic Ecology, “on a species level, many have increased, many have decreased, most are not too terribly far from no change and the data is not terribly far from centered on no change…,” adding:

…are we in a death spiral where common species and invasives are taking over and rare birds are taking it on the chin? Not in any general or on average sense, no. Quite the opposite, more than half the birds lost are from the 10 biggest losers that are all completely safe, often so widespread they are considered a nuisance, two of which are invasive, and most of which are declining because they got so big by exploiting habitat created/modified by humans in the first place which is now changing on them.

Study contradictions

Eng and Morrissey should have known better. Tellingly, an earlier study by the researchers had measured blood neonic levels in migrating birds captured at Long Point and found them far below those reported in this current study—a finding that seriously undermines the methodology of this current study not to mention the credibility of the authors, who failed to mention their own prior contradictory findings.

Another issue most reporters missed: Most sparrows in the experiment were unaffected; only those receiving the highest imidacloprid dose showed any symptoms and they recovered promptly and continued their migration. There was no evidence that the sparrows’ temporary sickness had any effect on the sparrow population overall.

Thus, the more one delves into the details, the more this research resembles the highly artificial and deeply flawed studies designed to stigmatize neonics by ignoring or purposefully eliding contrary findings and real world evidence. Perhaps most telling in this regard is that, just as with honeybees, the overall population trends completely contradict the bird-pocalypse narrative.

According to the Breeding Bird Survey, the population of White Crested Sparrows—the species chosen by Eng and Morrissey to support their bird-pocalypse narrative—has increased since the introduction of neonics in the mid-1990s. In fact, the trajectory of overall North American bird populations uncannily reflects the trends we’ve seen in honeybee populations: earlier steep declines that leveled off and in many cases started to increase, coincidentally (or not) as neonics came on the market and their use in agriculture increased.

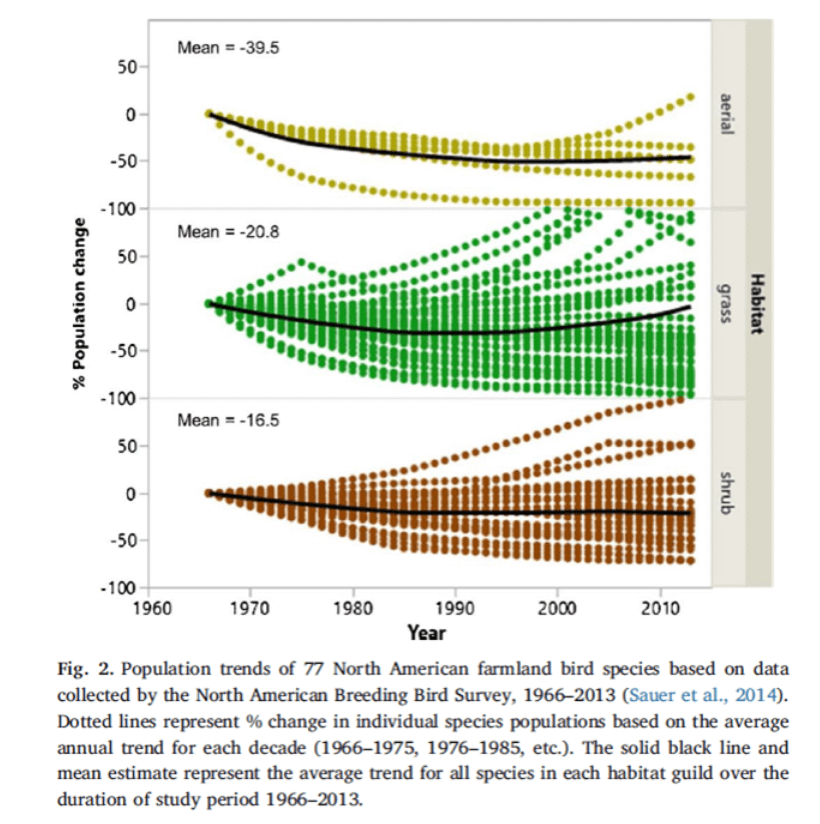

If Eng and Morrissey had wanted to check this, all they would have had to do was consult an earlier study on which Morrissey was a co-author. There you can find this striking graph of farmland bird population trends from 1993-2015. Divided into three “habitat guilds,” it clearly shows that average “aerial” and “shrub” populations stabilized in the mid-1990s, when neonics came on the market, while “grassland” bird populations began increasing. 56% of all species were increasing in number from 1993-2015.

Morrissey appears to suffer from selective amnesia when it comes to the results of her own studies that don’t fit this revised narrative she appears trying to advance. While cherry-picking data is distressingly common these days, it does serious damage to the credibility of the scientific enterprise and, in this case, the cause of protecting the environment and the effects on bird populations.

While the Eng study got lots of play in the media, which regurgitated the authors’ claims that neonics and agricultural pesticides in general are causing bird declines, other more carefully conducted large-scale studies that actually have looked into whether bird population declines are linked to pesticide use were ignored by the media.

One of the largest studies on this issue was published last year. A team led by Oklahoma State University’s Jason Belden examined bird population trends between 1995-2016 of 31 species along migration routes covering 13 states in the central United States, from Minnesota and North Dakota on the Canadian border to Texas in the south, and eastward as far as Ohio. While habitat did effect bird populations, agricultural land correlated with roughly comparable increases and decreases.

When evaluating the relative slopes of bird counts, there was not an overall consistent negative association between decreasing bird counts and increasing cropland…. If current agricultural practices were a major and widespread cause of bird declines, we would observe it across most species. These findings, the authors point out, “match previous observations across the United States that overall cropland and grassland (including pasture and rangeland) have been stable since the 1990s.”

Another study, by a UK team led by Rosie Lennon of the University of York, specifically looked at neonic exposures, finding no effects:

[T]here was either no consistent effect of dietary exposure to neonicotinoids on farmland bird populations in England, or that any over-arching effect was not detectable using our study design.

Favoring science over populist scares

If you care about birds, myopically targeting agricultural pesticides is an attractive, populist strategy but it is simplistic, wasting resources and more critically, time. The main culprits of bird death are well known, but it would be hard to work up much public enthusiasm to ban them. In order of magnitude, starting with the biggest bird-killers of them all, they are: cats, buildings, powerlines and motor vehicles.

Cats, both pets and feral, account for an estimated 1.5 to 4 billion bird deaths annually. According to an estimate by the US Agriculture Department’s Forest Service, cats, buildings and power lines account for 82% of bird mortalities annually, with vehicles contributing another 8%. Collisions with buildings (particularly those clad with reflective glass) account for between 100 million and 1 billion bird deaths per year in North America.

In the context of what we know about the birds and the bees—those allegedly facing extinction from crop protection chemicals—the Eng team study highlights the distressingly common tactics of scientists who appear more agenda-driven than science-based. Neonicotinoid pesticides are in their crosshairs, and they appear to have joined with activist campaigns in Europe and North America to get them banned.

It’s worked in Europe, where last year the EU adopted an almost total ban on the use of neonics outdoors. It might work in Canada, where that nation’s regulatory authority is proposing a 3-5 year phase out based on scientifically unproven grounds that neonic run-off from fields harms aquatic invertebrates in lakes, ponds and streams.

More responsible scientists and journalists are pushing back on the multiple versions of anti-neonics hysteria. As the science writer Peter Hess wrote in the online magazine Inverse earlier this year, “Global Honeybee Deaths Have Been Blamed on the Wrong Culprit All Along,” the real culprit in bee health is not insecticides but varrora.

With the honey ‘honeybee-pocalypse’, wild bee die off, and the ‘insect-Armageddon’ scares debunked, and the incipient farmland bird population scare unfounded, let’s hope that the US Environmental Protection Agency learns the proper lessons from the percolating ‘birds and bees’ story: Don’t let rational regulatory decisions get stampeded by agenda-driven ‘science’.

After all, neonicotinoid insecticides have proven to be enormously popular among farmers, translating into billions of cost savings for food-buying consumers. Discarding this valuable crop protection tool, which would require switching back to outdated chemicals that are known to kill bees and other beneficial species, and are proven carcinogens, is a questionable strategy.

Jon Entine is the executive director of the Genetic Literacy Project. Twitter: @jonentine