But it is hubris to think that material and technological progress makes our era totally discontinuous with the past, and that the experience of epidemics of plague, cholera, and other diseases that were a regular occurrence until recently has nothing in common with what we are experiencing.

We are in the midst of what Ed Yong of The Atlantic termed a “patchwork pandemic” – characterized by different geographic areas, different population groups, and different historical legacies. While the world awaits the development of an effective vaccine as well as treatments that can tamp down the ravages of a capricious virus, public health officials are exhorting us to rely on the most rudimentary, age-old tools for keeping the virus at bay – wearing a mask, hand-washing, and social distancing and lockdowns – in other words, treating people we don’t know as potential threats. Every virus and every bacterium has its distinct personality, and, yet, looking back at the history of pandemics, the ways in which human societies have responded to the upheaval and terror provoked by a poorly-understood microorganism have striking commonalities. For this reason, chronicles of disease outbreaks from the past can provoke a shock of recognition.

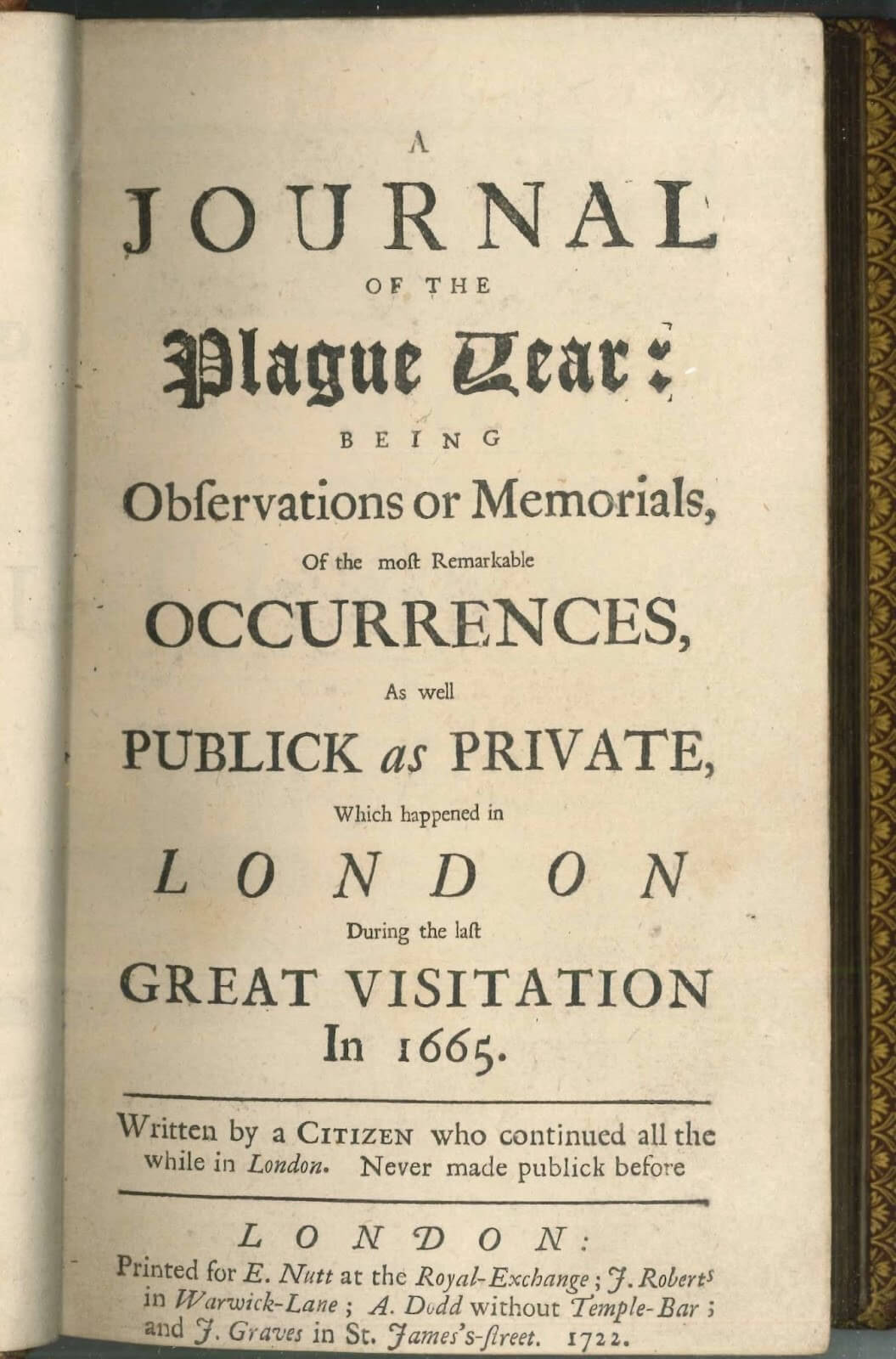

Daniel Defoe, author of the classic Robinson Crusoe, is also renowned for his classic description of an epidemic, A Journal of the Plague Year. Defoe was five years old when the bubonic plague came to London in 1665. He must have heard stories of the plague as a child, and in 1722 he published a gripping account of life during the plague. His Journal is a sleight-of-hand. Though actually a work of fiction written more than fifty years after the events, it presents itself as a contemporaneous, first-hand, neighborhood-by-neighborhood, eye-witness narrative of what life was like during the “visitation” by the plague. For his chronicle Defoe drew on a small library of contemporaneous accounts.

Owing to the vividness and immediacy of the narrator’s description of the effects of the epidemic on ordinary people in this street or that neighborhood of the city, the Journal has become the most famous account of the Great Plague of London, displacing contemporaneous accounts by actual witnesses.

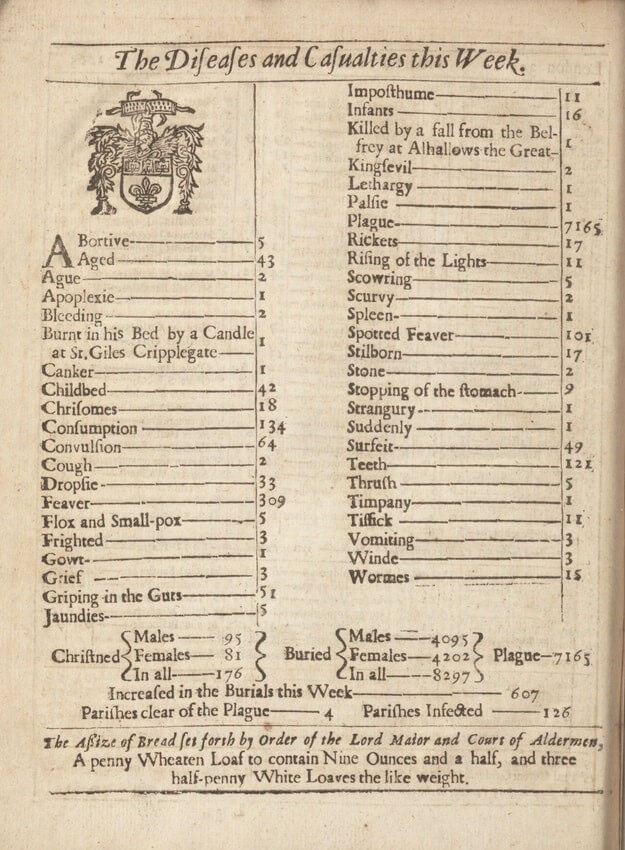

A failed businessman-turned-journalist, who started writing fiction later in life, Defoe originated a new style of writing that dispensed with aristocratic literary conventions, relying instead on empiricism and realism. His narrator tells us that his journal is based only on what he has observed directly in his walks about the city, what he has heard from credible persons, and the weekly “bills of mortality” published by the city of London. On occasion, he refers to events which he feels obliged to report but which he can’t vouch for.

As in Robinson Crusoe, the narrator of the Journal finds himself in a situation in which he must summon up all his wits and energy to survive an overpowering, incommensurate threat. While concerned for his own safety and his business, his single-minded focus is on the impact of the plague on the city of London, which is his protagonist. We are at his side as he describes what he sees as he moves about the city and provides his coordinates, which would have been familiar to any Londoner of the 18th century – “that is to say, in Bearbinder Lane, near Stocks Market.” The city’s inhabitants are characterized only insofar as they are affected by the “distemper” and make decisions about how to respond to it.

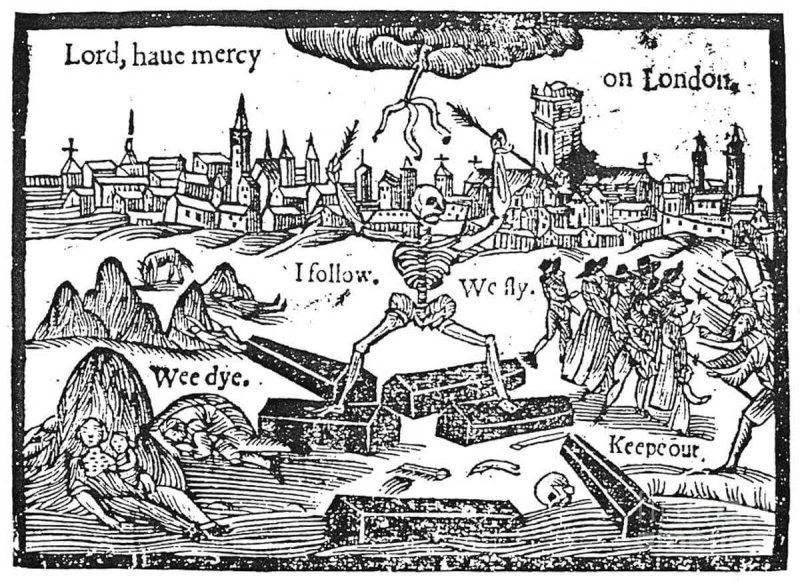

At first the plague, which the narrator tells us has come to London from Holland, manifests itself by a few isolated cases in the winter of 1664-65. But in February it flares up in parishes to the west of the city and gradually makes its way eastward, methodically visiting formerly untouched parishes. In the course of a year, it has reached every corner of England. Early in the outbreak the wealthy flee the city with their servants to their country houses, and the narrator, who initially considers fleeing, remarks that there were no horses left in the city.

In spite of his belief in Providence, the narrator emphasizes that transmission of the infection requires close personal contact, often within families, or with contaminated belongings, food, or cargo. Although the plague may have been sent by a Divine power to punish men for their sins, he makes clear that natural causes are entirely sufficient to account for the spread of the disease and its effects on its victims.

I must be allowed to believe that no one in this whole nation ever received the sickness or infection but who received it in the ordinary way of infection from somebody, or the clothes or touch or stench of somebody who was infected before.1

He describes the high transmissibility of the plague (which we now know to be caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, which was spread by fleas that fed on the black rat) and the unbearable sensitivity and pain caused by its pathognomic feature – buboes – which, he tells us, drove sufferers to throw themselves out of windows or into the Thames. He also notes that asymptomatic cases could spread the infection and that the disease can manifest differently in different people. Houses where people took sick were shut up and padlocked by order of the magistrate, and watchmen were posted outside day and night to insure – not always successfully – that the imprisoned could not escape. The narrator describes the pitiful cries that were heard from the street as family members discovered that a loved one had succumbed to the plague. Others, he tells us, died in the street. The bodies of the deceased were collected at night and taken to pits dug in churchyards or in open lots and buried en masse.

Defoe’s narrator describes the desperate condition of the poor, who, thrown out of work, could not buy food or other necessities for their families. In this situation, he tells us, they had no choice but to perform the most dangerous jobs created by the epidemic – tending to the sick and collecting and burying the dead. He notes that “the plague, which raged in a dreadful manner from the middle of August to the middle of October, carried off in that time thirty or forty thousand of these very people.” Once the plague makes itself felt, the common people, who are keenly attuned to astrological signs and portents, are desperate to ward off its spread and chase after an abundant array of fake cures and elixirs:

[The common people] … were now led by their fright to extremes of folly; … they ran to conjurors and witches, and all sorts of deceivers, to know what should become of them (who fed their fears, and kept them always alarmed and awake on purpose to delude them and pick their pockets) so they were as mad upon their running after quacks and mountebanks, and every practicing old woman, for medicines and remedies; storing themselves with such multitudes of pills, potions, and preservatives, as they were called, that they not only spent their money but even poisoned themselves beforehand for fear of the poison of the infection.2

Throughout his chronicle, the narrator anxiously scrutinizes the weekly “bills of mortality” published for each parish to gauge the progress of the infection. He knows from observing what is going on around him that the numbers of deaths attributed to the plague are grievously under-reported due to relatives’ fear of being stigmatized and the authorities’ connivance. He tries to judge the true magnitude of the deaths from the plague by examining increases in other causes of death and by comparing the overall death rate in a parish before the outbreak to the numbers when the plague was present all around him.

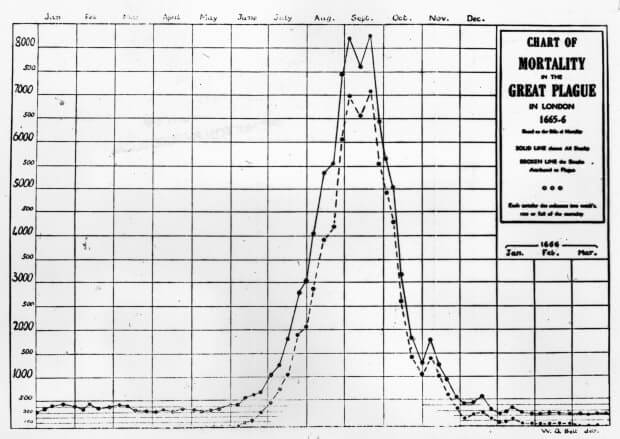

Deaths increased at an extraordinary rate in July and August, reaching a peak in September when, we are told, each week there were 8,000 or 9,000 deaths from the plague, and this he considers an under-estimate. Thereafter, the deaths began to decline precipitously, and the outbreak abated. According the bills of mortality, 68,590 people died of the plague, while the narrator claims that the total reached 100,000. This amounts to twenty percent of the population.

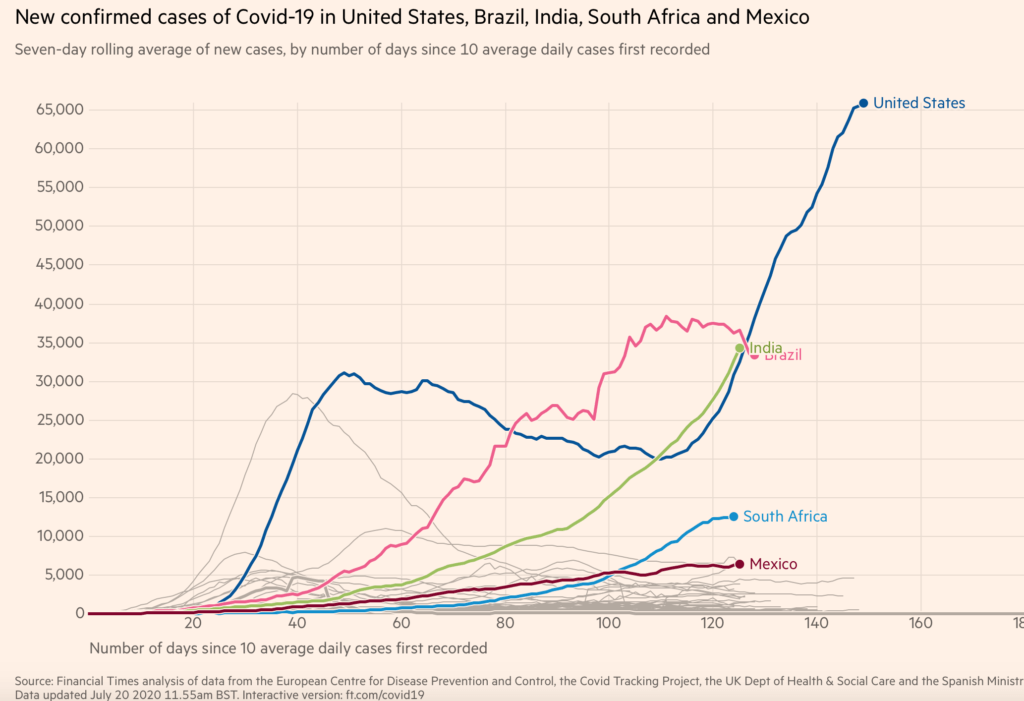

Looking back at the events after a half-century, Defoe knew the outcome of the “visitation,” and his account has a taught unity of time and place. Here in the United States, five months into the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, many observers are watching in horror and disbelief as the virus spirals out of control in states in the South and West that failed to take it seriously and refused to learn from the experience of other states, and countries, that succeeded in bringing their outbreaks under control. At the same time, some states and countries that successfully broke the chain of transmission, are experiencing resurgences.

For all the differences between the London plague and our pandemic, there are striking commonalities. As in Defoe’s London, the poor and the weak are disproportionately exposed to the coronavirus in low-income neighborhoods, close living-quarters, and low-wage jobs. As in Defoe’s London, many people refuse to follow common-sense precautions, instead falling for quackery and scientifically unsupported treatments. As in London, statistics regarding the number of cases and deaths from Covid-19 are manipulated and misinterpreted to suit the narrative of different parties.

On the most basic level, what we share with the London outbreak is the massive, sudden upsurge in morbidity and mortality, and the inescapable sense that a pathogen is beyond our control. In London of 1665 the bills of mortality were widely distributed so that residents could know the situation in their parish, and neighbors shared the latest news of who had fallen ill and died. In 2020, normal life has been replaced by a profusion of images, charts, statistics, and stories, which have flooded the media since March. These convey the fever chart of the epidemic in different places together with stories of intensive care units stretched to capacity and the bios of individuals who have been lost. At the same time, we are subjected to a constant flow of interviews with health care workers, epidemiologists, and public health officials, who interpret the day-to-day trends in an effort to explain where things are headed.

Although we pride ourselves on being modern and are used to thinking that we have control over our lives, at the present moment we have to admit that we have no idea of how this “visitation” will play itself out.

References:

-

Daniel Defoe, A Journal of the Plague Year, Penguin edition, 1966, p. 206.

-

A Journal, p. 30.

Geoffrey Kabat is an epidemiologist and the author, most recently of Getting Risk Right: Understanding the Science of Elusive Health Risks. Geoffrey can be found on Twitter @GeoKabat