There is increasing confusion, and even consternation, over what seem to be disparate policies, recommendations, and mandates emerging in response to the current surge of COVID-19 infections and hospitalizations in much of the country. Masks or no masks? Vaccine mandates versus voluntary vaccination? Proof of vaccination for admission to bars and entertainment venues?

The zeitgeist was nicely captured by a Michael Ramirez cartoon that depicted the confusion sowed by the shifting and sometimes contradictory recommendations about the necessity of wearing masks.

The patchwork of policies and what some have derided as “moving the goalposts” is not surprising. Data constantly become available and circumstances change, and so must our responses. The situation is somewhat similar to the way that our automobile navigation systems work. When you start the journey, the device provides an estimated time of arrival (ETA) and plots the route, but that can change according to various unplanned occurrences—if you decide to stop for coffee or encounter an opened drawbridge, for example.

The operative concept for managing the pandemic, or any medical problem, for that matter, can be summarized in a single phrase: minimizing the probability of adverse outcomes. But we, as individuals, public health officials, and political leaders, have widely differing tolerance for risk, and the risk-related circumstances vary widely in different states and localities. One size doesn’t fit all.

Managing probability

We know that there are various “non-pharmaceutical interventions” (NPIs) that can lower the likelihood of contracting or spreading COVID-19. These include wearing a mask, avoiding crowded indoor spaces, practicing social distancing, washing hands frequently, and of course, getting vaccinated.

So, to control the pandemic, we need to manage probability—more specifically, to reduce the chances of being exposed to an amount of the SARS-CoV-2 virus sufficient to penetrate the natural and vaccine-induced defenses that can cause an infection and to spread it. At the same time, we must not impose measures that cause diminishing returns. The cure should not be worse than the disease. It’s a difficult balancing act.

Some of the barriers to infection are illustrated nicely in this figure below, the original version of which was created by Australian virologist Ian Mackay:

Each of these measures lowers the probability that an infectious dose of virus will find its way to your respiratory tract, and if it does that it will cause an infection. Also, depending on the effectiveness and extent of vaccination, some of the other interventions could become superfluous.

Such strategies are the essence of preventive medicine. For example, many of us take drugs to lower our cholesterol levels or blood pressure to reduce the likelihood of cardiovascular disease, and get flu vaccine to prevent influenza.

Evolution factor

Erecting barriers—biological, physical, and behavioral–to prevent infection is well understood. What is harder is predicting how the pandemic will evolve, and what responses will be required. There is a wide spectrum of possibilities, which are dependent upon… probabilities. SARS-CoV-2 could become less lethal and evolve into a virus that is endemic in the population, similar to other coronaviruses that cause colds, or remain a serious threat. Or it could become even more virulent.

Keeping in mind that the ultimate telos, or life goal, of pathogens is to “go forth and multiply,” there’s no particular advantage to killing their host. Arguably, a respiratory virus proliferates best when infected hosts are able to mix with other people and breathe on them; and the longer the asymptomatic, contagious period, the better for spreading infection.

Consider pandemics of influenza, the “flu” virus, to which SARS-CoV-2 is sometimes compared. Flu outbreaks taper off each winter when we reach “herd immunity,” when enough of the population becomes immune either through infection or vaccination that the virus has difficulty finding new, vulnerable hosts. For COVID-19, trying to attain immunity through natural infection is not a good option, because of the high frequency of persistent symptoms: profound fatigue, fever, brain fog, and loss of taste or smell, in as many as 30% of people who recover from the acute infection.

One of the most vexing questions is the long-term effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccines. Will they confer long-lasting protection, like the lifetime immunity after smallpox vaccination, or will immunity wane? There is evidence that the immunity induced by the Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccine diminishes about two percentage points per month.

Also worrisome is a report of an outbreak of COVID-19 in both vaccinated and unvaccinated people in Provincetown, Massachusetts in July. There were 469 people with COVID-19, 74% of whom were fully vaccinated, following large July 4th holiday gatherings. The Delta variant was identified in 90% of virus specimens from 133 people. (More than three quarters of the vaccinated individuals who were infected with COVID-19 reported symptoms such as cough, headache, sore throat, or fever. Four had to be hospitalized.) By the end of July, the count of infections had risen to almost a thousand, illustrating that irresponsible behavior can overcome the protection afforded by vaccines.

Could it get worse?

Finally, public health officials and virologists are concerned about new, even nastier mutants, or “variants of concern,” that might evolve to evade protection from the existing vaccines. Again, that’s a matter of probability, which increases with the number of COVID-19 infections, every one of which creates more mutants that Darwinian evolution will test for “fitness”—that is, the ability to spread and to overcome vaccine-induced or natural immunity.

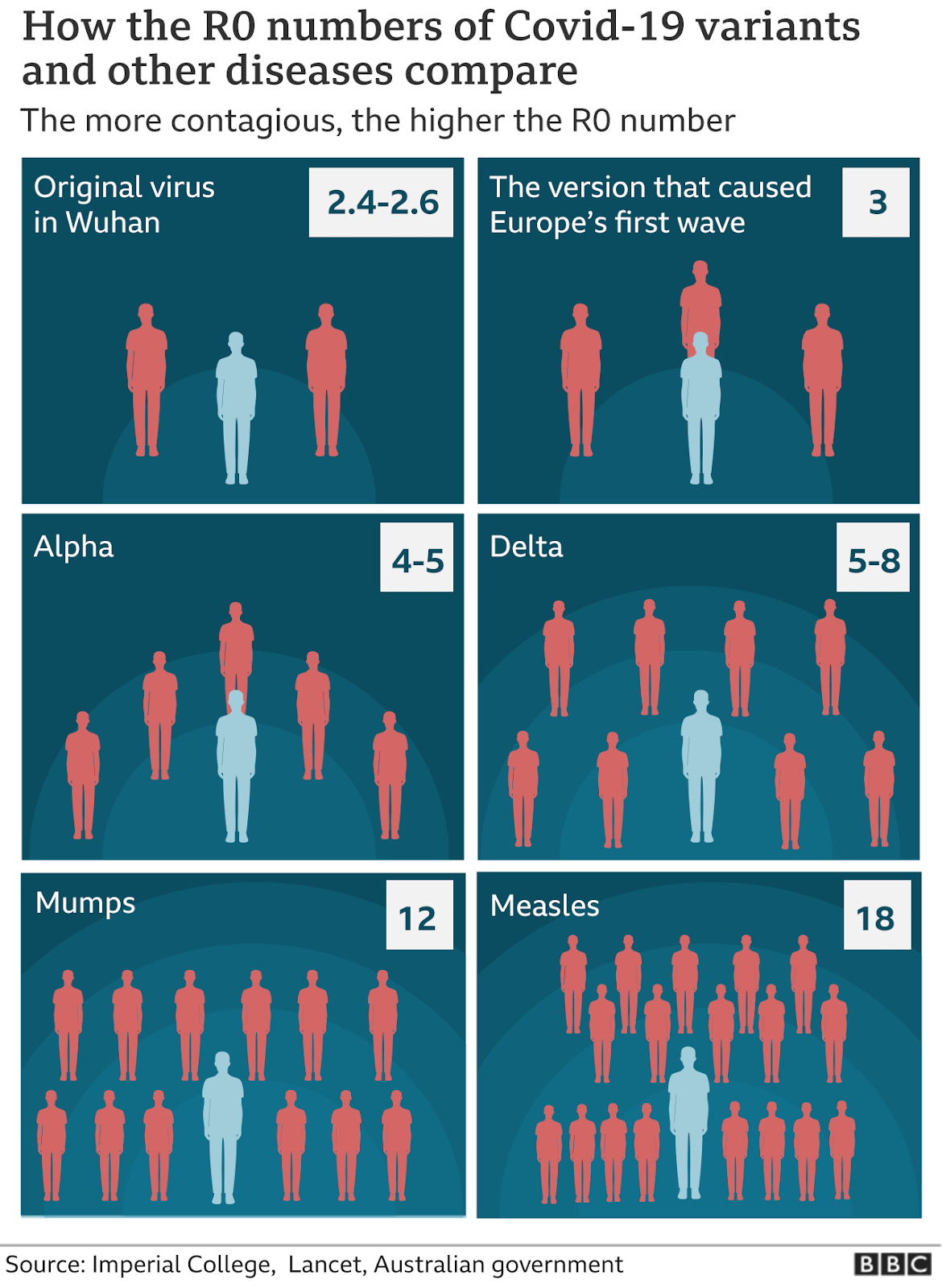

As shown in the graphic below, the SARS-CoV-2 virus already has evolved to become roughly two- to three-fold more transmissible than the original Wuhan virus. (R0, or R-naught, is the number of people that an infected person could infect in the absence of any protective interventions.)

To spare patients the suffering of the acute and persistent symptoms of COVID-19 infections and also to reduce the probability of new, more transmissible and more virulent variants arising, we are back to needing to “flatten the curve” of infections. With the interventions shown on the Swiss cheese respiratory virus graphic, we can lower the likelihood of exposures and infections. We should use them.

Henry I. Miller, a physician and molecular biologist, is a Senior Fellow at the Pacific Research Institute. The co-discoverer of a key enzyme in the influenza virus, he was the founding director of the FDA’s Office of Biotechnology. You can find him online or on Twitter at @henryimiller and read more of his writing at henrymillermd.org.