This past Christmas was not the best of times for Cubans. It was difficult to find food such as chicken, meat, milk and eggs and other basic supplies in state stores. This long-standing shortage has worsened in recent years, exacerbated by the COVID-19 health crisis and disruptions in the global food economy caused by the war in Ukraine.

Cuba, contrary to popular myth, maintains international trade with several countries in the world (Cuba’s main trading partners include Venezuela, China, Spain, Canada, Mexico, Brazil and the Netherlands), exporting more than $1.15 billion and importing more than $3.4 billion in 2020.

The majority of imports — $1.8 billion — are foodstuffs such as wheat, meat, corn, rice and milk; 80% of the food consumed by the country’s 11.2 million citizens is imported, making it even more vulnerable to global supply shortages, which soared in 2022.

Rising food insecurity has pressured the Cuban regime to take urgent measures to control scarcity. For example, it relaxed import regulations and eliminated the limit on quantities and import tariffs from July 2021 to June 2023. The government led by Miguel Diaz Canel also launched a “food sovereignty” plan to increase domestic agricultural production. Surprisingly to some, this plan integrates both agroecology and the use of genetically modified (GM) crops as positive tools for farmers.

Cuba is not only facilitating the use of many imported GM crops, but those developed locally by its own scientists. That upsets ‘progressives’ across Latin America who disproportionately reject many disruptive technologies such as agro-biotechnology — an anathema among ideologues.

The birth of Cuba as a biotech hub

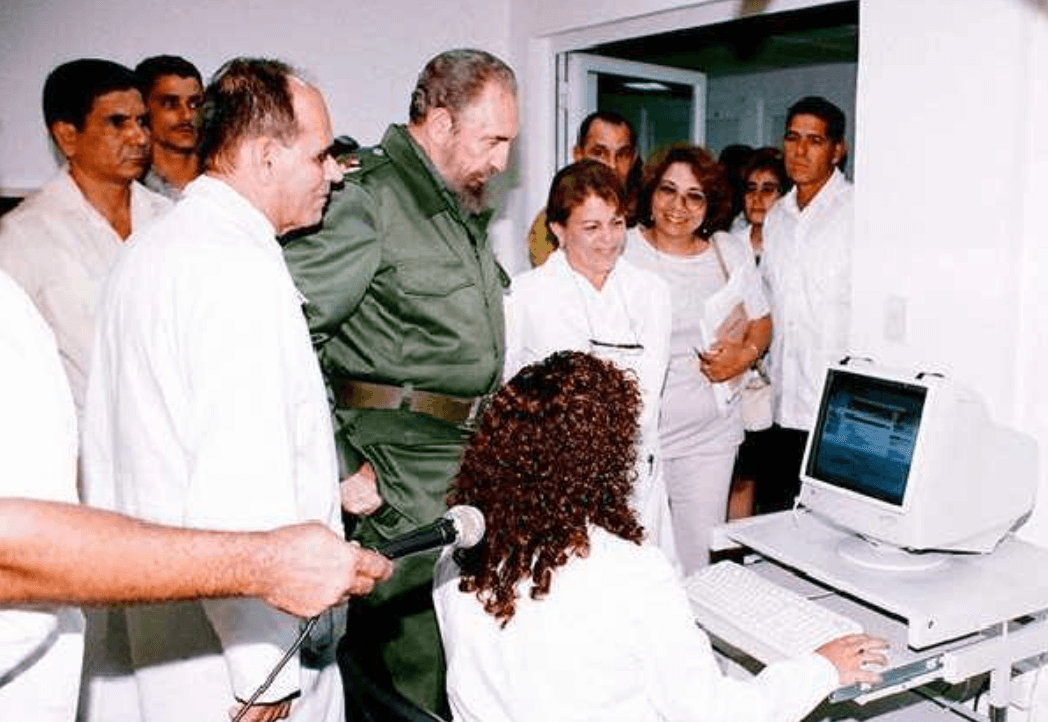

To understand how Cuba came to locally develop genetically modified crops we need to go back a few decades to the Fidel Castro era. From the beginning of his regime, the late dictator voiced crucial importance to the country’s scientific and biotechnological development. By the early 1980s, he began to articulate the formation of a cooperative collection of biomedical research institutions that would later give rise to important inventions in vaccines and medicines.

Castro himself founded the Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (CIGB) in 1986. In his inaugural speech he recounted the vicissitudes it took to build this research center and how he was personally in charge of sending Cuban scientists to train in Europe and the US for the local production of interferon and other pharmaceutical products.

Since the 1990s, a powerful biotech research community has emerged on the island, with more than 50 related research institutions and thousands of researchers and workers. In 2012, these institutions became part of the state-owned business group BioCubaFarma, which became responsible for about half of the research carried out on the island, and has among its objectives the export of pharma products.

This state-owned holding company has developed several vaccines for the Cuban population to help control of meningitis B/C and hepatitis B; developed technologies for the diagnosis of neural tube defects, dengue, and pregnancy kits; vaccines that might eventually limit lung cancer; and medicines to fight viral diseases, myocardial infarction and organ transplant rejection. It has developed a portfolio of diverse products, including bivalent, trivalent, tetravalent and pentavalent vaccines, and therapeutic products to combat AIDS by delaying the onset of the disease in people already infected.

These research capabilities enabled Cuba to develop its own vaccines to combat the SARS-COV2 virus. This includes the Soberana, Mambisa and Abdala vaccines. The latter has already passed Phase III trials but is still awaiting WHO endorsement.

GM crops “made in Cuba”

The agricultural was also involved in biotech innovation. Institutions such as the CIGB and the National Institute of Agricultural Sciences (INCA) focused on the development of recombinant enzymes for the food industry, vaccines and veterinary drugs and plant breeding -conventional and biotechnological- focused on key crops for the country such as corn, soybeans, beans and sugar cane, in addition to plants that function as biofactories.

The press in Cuba never demonized GM crop innovation as was the case in some other left-leaning countries. Well reported and positive stories can be found in Granma, the official newspaper of the Cuban Communist Party, and CubaDebate, a group of journalists that defends the Cuban regime.

The first transgenic plants created at laboratory level in Cuba by the CIGB date back to 1996 -specifically a tobacco that produces the monoclonal antibody Hep-1. In the mid-2000s, Carlos Borroto, then vice rector of the CIGB, reported that “among the most advanced GMOs, there are varieties of pest-resistant corn and sweet potatoes, rice immune to fungi, and tomatoes unaffected by viruses”.

In 2004, a collaboration among CIGB, the Liliana Dimitrova Horticultural Research Institute and the Cuban Grain Research Institute, developed a GM corn called FR-Bt1, that is resistant to fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) and tolerant to the herbicide glufosinate. In 2009, this Bt corn variety obtained safety permits; the first production trials -on 900 hectares- achieved 4 tons per hectare, more than double the national average at the time.

By 2013, more than 3,000 hectares of Bt corn were reported being grown as part of a government plan to reduce production costs.

Merardo Pujol, a plant breeding and GMOs expert at CIGB, commented:

The image that people want to convey that something more natural is closer to the average citizen is false. Organic products are much more expensive than those made with advanced technologies. If you voluntarily deprive yourself of the use of a technology, of an alternative, of a source of employment, in the end you end up using the products that other people produce and get more out of them.

Another research project implemented by a partnership between CIGB and INCA is the production of an herbicide-resistant GM soybean, which in experimental plots showed a yield of up to 2.8 tons/ha, much higher than yields for non-GMO varieties. In 2015, some 500 hectares of production with this GM soybean were already reported in Ciego de Avila Province.

Biotechnology addresses food shortages

The high food imports during the five-year period 2014-2018, with an expenditure of more than $1,045 million dollars, added to the ongoing food crisis that Cuba is experiencing, led the government to scale up the production trials of GMOs and the approval of regulations from 2020.

In July of 2020, Cuban scientists created a National Commission for the Use of GMOs, under the supervision of the Ministry of Science, Technology and Environment (CITMA), aimed at the orderly use of this biotech techniques, as an alternative for national agricultural development. The vice minister of CITMA, Armando Rodríguez, commented that supporting GM crops “complements” conventional agriculture and agroecology. GM crops mesh well with “Tarea Vida”, a state program to address climate.

The 2020 harvest included trials in various provinces. The yield achieved in his field speaks for itself: 6.20 tons per hectare, the highest ever recorded in a province where historical yields were only 0.6 or 0.7 tons per hectare.

Said farmer Félix Álvarez at the First National Workshop on GM crops held:

This is incomparable with any other corn. We have had the problem of the Palomilla pest for a long time and every day it becomes more difficult to control it. Now we have not seen one, the plant is strong, with development. That is what was needed at this time.

Addressing potential risks, Dr. Enrique Rosendo Pérez, Director of the CIGB in Sancti Spíritus, stated that “the GM events that we are introducing are recognized and studied for more than 20 years and there is no scientific evidence that has demonstrated adverse effects on humans.”

All the corresponding toxicology studies have been done, nutritional studies, the license for human use and consumption was granted by the country’s regulatory body, the strict biosafety licenses and the Cuban law for the use of genetically modified organisms were taken into account. Today transgenesis is as controlled as other forms of classical genetics have never been before”

Are there serious unknown potential dangers as GM critics claim? According to farmer Reinel Tomé:

I prefer to consume 10 times a GM crop than one where a chemical is applied. The farmer who has brains looks for technology. In GM crops, there is no need to weed. I used to have 60 workers doing it and now I get by with just a few. It costs me less. My field is experimental so I can draw my own conclusions.

According reports, some 8,500 hectares of Bt corn were expected to be planted in the spring of 2021 in different parts of the country, beyond the 38,250 tons already expected to be harvested. Scientists reported successful field results at the end of 2022 planting a pioneer soybean resistant to Asian rust which can’t be easily contained.

In a webinar last August by ChileBio (watch it in full if you understand Spanish), Dr. Mario Pablo Estrada, Director of Agricultural Research at CIGB, said that by 2024 Cuba expects to add between 50 and 100 thousand hectares of local Bt corn and herbicide-tolerant soybean. Scientists are also working in collaboration with EMBRAPA, a Brazilian state company, to develop gene-edited beans.

Latin American left-wing opposition to crop biotechnology

Many Cuban scientists are on a mission to promote advanced biotechnology in farming. “The revolution of GM food crops has meant as much for the welfare of humanity as that of artificial fertilizers at the beginning of the 20th century,” wrote Dr. Luis Montero, former President of the Scientific Council of the University of Havana and Cuban Society of Chemistry and member of merit of the Cuban Academy of Sciences in an opinion column.

Certain transnationals companies are important promoters of these crops for their commercial benefits. You can have the corresponding opinion regarding the negative action of some entities. However, the scientific truth can be wielded as much by a monopolistic and exclusivist organization as by a revolutionary biopharmaceutical laboratory, owned by the people.

This vision of political and governmental support for GM technology contradicts the rejectionist views propagated by many leftist politicians and parties in Latin America. This issue, like climate change, has become more and more politicized in recent years. Latin America takes some of its cues from the United States where there are deep ideological biases on science issues, such as rejecting biological evolution and anthropogenic impacts on climate change among Republicans/conservatives, and in turn, Democrats/liberals skeptical of nuclear energy and genetic modification of crops.

Three leftist presidents in Latin America have endorsed moratoriums on GMOs: Hugo Chavez in Venezuela, and more recently, current President Nicolás Maduro extended the moratorium even to research in 2016; former President Ollanta Humala in Peru in 2011, and later the left-wing congresswoman Veronika Mendoza who worked with activist groups to extend the country’s GMO moratorium to 2035; and Rafael Correa in Ecuador (although a few years after he signed the legislative ban, he publicly said he regrets doing so and considers it a “mistake“.

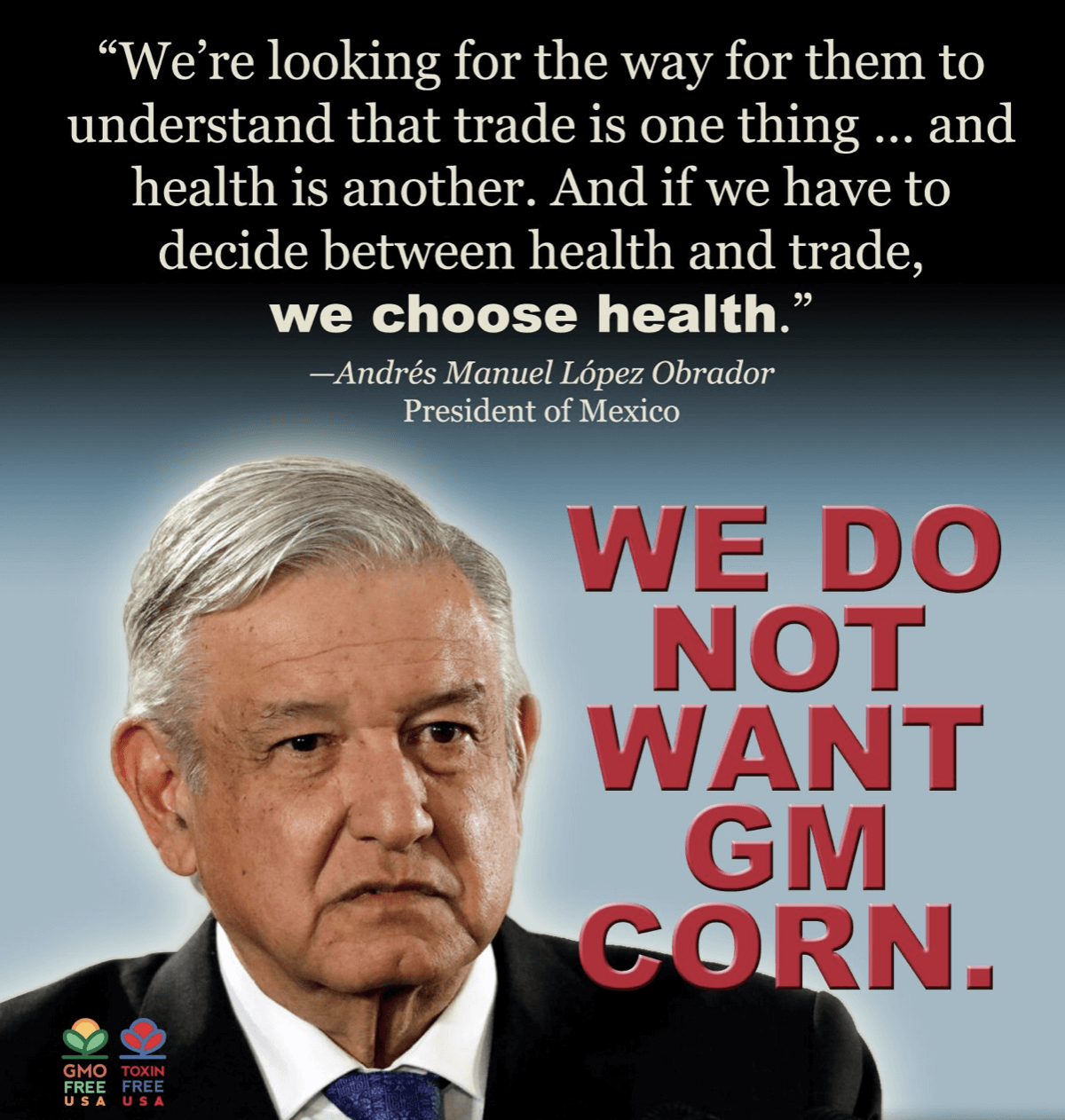

Evo Morales, former president of Bolivia, has blamed GMOs as the cause of “baldness and homosexuality”. Current Columbian President Petro said in 2017 that GMOs “have unpredictable consequences on human health” and that Colombian officials in researching agro-biotechnology were “subordinated to particular interests”. The current president of Mexico, Lopez Obrador, is opposed of biotechnology and the herbicide glyphosate; his ban decrees recently escalated into a conflict with the US for including the importation of GM corn. Activists in the US and around the world have turned his rejectionism into a propaganda campaign.

Not all anti-GMO efforts have been successful. An influential leftist senator in Chile tried but failed to establish a ban on GMOs a decade ago. In Colombia, a leftist deputy tried but failed to bring a moratorium bill to congress; and in Argentina, a leftist deputy introduced a bill to ban HB4 GM wheat.

Cuban lesson and ‘food sovereignty’

What are the most repeated claims by Latin American leftist politicians to oppose GM crops? They stress concern for food safety; believe their countries can be fed with organic farming and agroecology; claim a corporate international conspiracy to push GM technology by “multinationals”; and maintain that GM crops, in circulation for 30 years now, have not been adequately evaluated to assure their safety.

Who better to respond to these concerns than leftists including Cuban scientists?

Dr. Luis Montero has noted:

[About] claims that in the future we will better know what GMOs can do… absolutely not. We know whether they are or are not toxic… There is enough knowledge today to predict virtually any harm that can occur in the accumulation of foreign substances … and [GMOs] definitely don’t produce foreign substances

“Several Nobel Prize-winning scientists and more than 200 institutions assure its use through 25 years of research on its benefits, both for human and environmental health, According to Dr. Mario Pablo Estrada, there are clear benefits already established:

The direct benefit [of GM crops] translates into a reduction in the use of chemical agents, while indirectly makes biological controls more effective than conventional ones that rely on pesticides. Therefore, GMOs help mitigate carbon dioxide and methane emissions, while increasing yields.

Estrada on biodiversity:

The fauna in the soil is richer in GM crops than in non-GM crops: first, because less chemicals are used, and second, because the plants are healthier.

Countering the oft-repeated argument that GMOs are a monopoly promoted by multinationals, it should be noted that a huge amount of research into commercial GM crops were developed in various countries by state research institutions and public research centers.

Asian has been a center of GM research. China has a strategy of developing GM and gene-edited crops at the state level. India funds GMO research on more than 13 types of crops; the Philippines, drawing on research from public-state institutions, has finally bring Golden Rice to large-scale field production; Bangladesh developed Bt eggplant for use by small farmers, which reduces pesticide application to near zero.

In Africa, Nigeria commercially approved a pest-resistant GM bean in 2019, and Kenya did the same for a virus-resistant GM cassava in 2021 -both state-owned developments. In Latin America, Brazil’s state-owned EMBRAPA, brought its virus-resistant GM bean to the market shelves in 2021, while Argentina started commercial production of drought-tolerant HB4 wheat during 2022, a crop born in the local public sector.

Cuban researchers see the current phase of GM crops development as a boon for the developing world. According to Dr. Estrada:

GMOs initially emerged in industrialized countries, developed by large companies to solve a problem in those countries. But the companies that later began to work with biotechnology were different, in different countries and thinking about local needs. If we condemn technology for the interests of the countries, we will never develop ourselves.

These global developments should at least prompt the global left to pause their hostility towards GM innovation, especially at a time when activists raise the concept of food sovereignty. If food sovereignty — a vague and never clearly defined goal — means that a country can produce all the food its population needs, something technically impossible, or at least reduce food imports as much as possible, that’s all the more reason we need regulations that encourage the development of disruptive technologies — all the potential tools in farmers’ toolboxes should be made available.

Peremptorily banning GMOs or other biotech techniques is shooting ourselves in the foot — a “food and environmental suicide” — in times of tremendous challenges in food production, international conflicts and climate change.

The famous Cuban poet José Martí wrote that “in revolution, the methods must be silent, and the purposes, public”; the GMO revolution in Cuban agriculture has perhaps gone unnoticed. It’s time that its potential is promoted among the regulators and decision makers of other countries with similar left-leaning political ideologies. Without the use of GMOs and new biotech techniques, there will be no real “food sovereignty”, let alone the ability to feed vulnerable people in an environmentally sustainable way.

“Renouncing GMOs is not a utopia, it is an outrage,” Dr. Montero has warned.

“There is no conflict between ecological agriculture and GMOs… GMOs can help in agroecological agriculture to produce more through more environmentally friendly methods. Please use them.”

Daniel Norero is an agricultural engineer, with previous training in biochemistry at the Catholic University of Chile. He is co-founder of the precision breeding startup Neocrop Technologies and a BTI Alliance for Science Fellow. Find Daniel on Twitter @DanielNorero