Since 2000, the EU has adopted a very hostile stance towards GMO crops, and it’s carried over into its opposition to new plant breeding techniques (NPBTs), such as CRISPR gene editing. Unlike in many other countries, including the US, Brazil, Japan, England, Canada and Argentina, the next generation of European crops will not be pesticide resistant and more nutritious, or tweaked to resist disease, drought, flooding and browning.

Although there are 60 GMO crop varieties approved for European import, mostly as animal feed, only one variety of corn is grown in the EU.

Commercial cultivation of GE crops in the EU is limited to one percent of the EU’s total corn area (corn is the only approved crop representing approximately 68,000 hectares and 2,000 hectares are grown in Spain and Portugal respectively).

According to a remarkably candid 2022 USDA Foreign Agricultural Service assessment, the future for transgenic and gene edited crops in Europe is bleak.

The threat of destruction by activists and difficult marketing conditions … discourages the cultivation of GE crops in general. For more than two decades, lack of appeal of GE foods over traditional ones combined with consistent fear mongering campaigns from anti-biotech groups resulted in overall negative attitudes of European consumers toward GE products.

Supporters of GE saw a glimmer of hope in April 2021 when the European Commission (EC) published a study promoting new breeding techniques, including CRISPR as a potential tool to achieve the ambitious targets of the EU’s Farm to Fork and Biodiversity Strategies. A draft policy report is scheduled for release in June.

In another promising development, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) ruled in February that organisms derived by in-vitro random mutagenesis, a form of genetic modification, are excluded from the stringent regulations governing GMOs. Random mutagenesis, which has been utilized since the 1930s to develop new varieties of existing crops, involves using chemicals, X-rays, gamma rays and ultra-violent light to produce a desired trait in a seed.

More than 3,000 plant varieties have been developed over the decades including sweet red grapefruits and varieties of durum wheat. In-vitro random mutagenesis was exempted in the 2018 ruling by the European Court of Justice, but a French court challenged that judgement, determining that in-vitro mutagenesis should be subjected to GMO regulations. The ECJ rejected the French ruling, noting that considering “the long safety record with regard to these applications”, plants derived from in-vitro mutagenesis should be excluding from complying with the existing GMO guidelines.

Politics and new plant breeding techniques

Political support for NPBTs is gradually increasing throughout Europe. The disruptions caused by the Ukrainian-Russian war and climate disruptions has spurred some converts.

- Several Italian Members of the EU Parliament have endorsed gene-editing and other new breeding techniques in reaction to the heat waves and droughts experienced in Europe.

- “New genomic techniques can promote the sustainability of agricultural production, in line with the objectives of our farm to fork strategy,” said Stella Kyriakides, EU commissioner for health and food safety.

- According to Antonio Tajani, a former EU Commissioner in charge of enterprise and industry, “New agricultural biotechnology can provide experimentation for more drought-and pest-resistant plants” and these techniques should be dissociated from the EU’s 1999 GMO Directive.

- Herbert Dorfmann, another Italian European MP, has commented: “We need the kinds of crops which are more resistant to drought. And that is why we need the forms of genetics, which can be used to that end, and that is why we need to legislate … so that we can use these technologies across Europe.”

- Czech agriculture minister Zdenek Nekula maintains that the EU’s current framework for gene-editing is a “limitation for European farmers which brings about brain drain to countries outside of the EU. … EU farmers could be helped by using innovation. … We need to support new genomic techniques.”

- “Gene-editing techniques are a magnificent tool to ensure that crops need less water, fewer plant protection products and fertilizers, and are more resistant” to climate change,” said Luis Planas, Spain’s Agriculture Minister.

Agriculture ministers from a majority of EU nations have now signaled support for looser regulations on crop biotechnology, citing the need to mitigate fertilizer shortages, drought, and declining soil fertility that threaten European farming. Italy, Sweden, Czechoslovakia, Lithuania, Netherlands, Malta, Ireland, Hungary, Netherlands, Romania, Estonia and Belgium back adoption of new gene-editing techniques. In March, the British Parliament approved the Genetic Technology Precision Breeding Act, which will allow the use of new gene-editing technologies for both plants and animals if labeling requirements and other technical issues can be resolved. However, the bill only covers England; the use of these new technologies will remain illegal in Northern Ireland, Wales and Scotland.

France, whose support is critical for EU acceptance, is supportive, but wary of getting too far ahead of slowly evolving public opinion. “We must be able in France, in a controlled, open, transparent way, by giving democratic guarantees, to carry out innovations which make it possible to advance in practices and to have both productivity and better resistance to hazards and risks, President Macron declared in 2021, “New Breeding Techniques are part of it.” Last September, France’s agriculture minister cited gene editing as a climate solution, noting that gene-edited crops can help bolster food security and sustainability.

The question of Germany

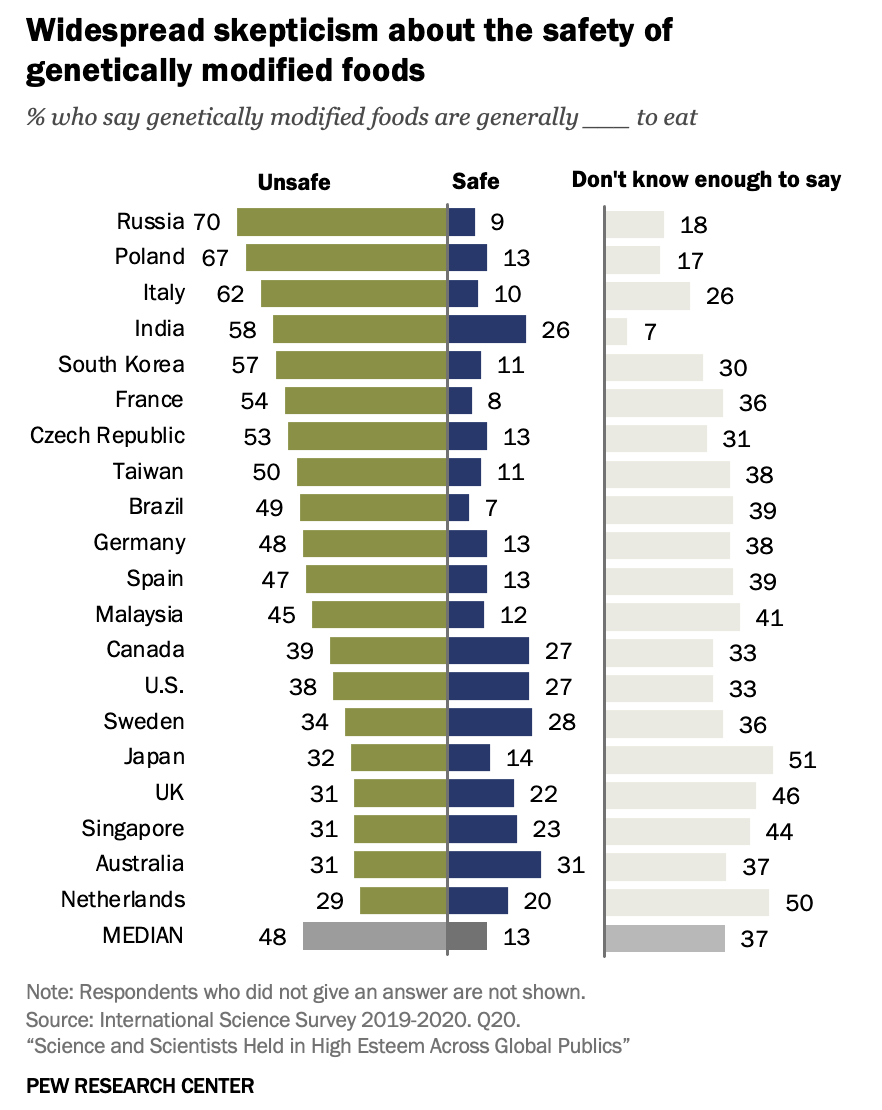

Germany’s position as the largest economy, most populous country, and the largest contributor to the EU budget is pivotal to the possible adoption of GE crops in the EU. Most German farmers and scientists support adoption of gene editing. But if the EU is ever going to vote to adopt genetic engineering to cultivate crops, it must overcome strong political and grassroots opposition. That seems unlikely. A 2020 Pew Research Poll on perceptions of GMOs in 20 major countries indicated that most Germans are skeptical at best; just 13% of those surveyed considered GMOs to be safe.

There is some irony in Germany’s skepticism, among the most intense across Europe. According to the USDA, “Germany … remains a major consumer of GE products since it imports nearly six million metric tons of soybeans and soybean meal for animal feed annually.” The EU is the largest regional consumer of GE food products, almost all of it transgenic animal feed.

Numerous world-class seed companies are located in Germany, notably Bayer, BASF, and KWS. “These international companies are major suppliers of both GE and conventionally bred seeds to markets outside of Europe,” the USDA report noted. “However, the companies have since moved research and development operations for GE crops to sites outside of the EU, for example the United States, and to other countries including Brazil, Argentina, South Africa, India, China, and Japan.”

There is almost no political or public support outside of the agricultural and scientific community for new breeding techniques. The coalition agreement that established the present German government, which includes the Social Democratic Party, Greens and Free Democrats, did not mention terms such as “genetic engineering”, “gene technology”, “new genomic techniques” and “new breeding methods,” as the coalition partners disagreed on the issue.

The Social Democratic Party opposed GE in its party platform when it was part of the previous government with the Christian Democrats and in the prelude to the September 2021 elections, stating: “We will continue to say No to genetically modified plants.”

Svenja Schulze, a Social Democrat, who was the German Minister for the Environment in the previous coalition government between the Christian Democrats and the Social Democrats (SDP), has urged continued regulation that would effectively stymie the development of crops utilizing new breeding techniques.

The Green Party has consistently opposed genetic engineering, and it was a major part of their platform in the September 2021 Parliamentary elections. The party insisted that all new plant breeding technologies should continue to be strictly regulated as genetically modified organisms.

Only the Free Democrats, the junior member of the three-party coalition, publicly backs NPBTs, emphasizing the great potential of GE for biodiversity, soil and efficiency, urging a regulatory regime that is “science-based.” The party’s vice chief, Carina Konrad, has pushed for it, stating: “With new breeding technologies, we can boost yields without risking sustainability.” However, the party does not hold any of the ministries that make GE policy, such as Agriculture and the Environment, and therefore has little influence on government policy on this issue. It is highly unlikely they would break up the government to push for relaxing regulations.

Crushing filaments of dissent among Green politicians

There appears no room among German gene-editing opponents for compromise. When a small group of Green MPs, including one EU lawmaker, issued a paper in 2020 supporting the use of gene-editing technologies, they were harshly rebuked by the party. It called for a “modern” approach to regulation of GE, claiming gene editing could play an important role in “improving sustainability” offering opportunities “for a healthy planet and thus for the good of people and the environment.” The dissidents urged open debate to “discuss and define areas of application based on risks and opportunities”, asserting that blanket rejectionism “no longer corresponds to the current state of science” and works to promote monopoly structures in agriculture.

Green MEP Viola von Cramon-Taubadel, one of the paper’s co-authors, said, it was written “to gear the debate towards evidence and science-based politics rather than ideologically driven debates”:

The current regulation is very contradictory…. The fact that gene technologies such as CRISPR are used regularly in medical research but not for agriculture is incoherent and needs to be fixed. This kind of overregulation is…an obstacle for Small and Medium Enterprises …it’s very bureaucratic, costly and inhibitive.

Hardliners at Greenpeace and elsewhere were aghast. Its EU food policy director, Franziska Achterberg, called it “quite unbelievable that anybody who defends high ecological and social standards” should be in favor of weakening EU GMO standards.… [Agrichemical corporations] “stand to profit from the patents on GM technology and seeds, but it’s not clear why anyone in the Greens would agree with them.”

Steffi Lemke, environment minister and Green Party member, adamantly opposed liberalization:

I find the current regulation to be exactly right because it upholds the precautionary principle…. There is no need for a new revision…. Genomic techniques can of course also have negative impacts on agriculture: They can lead to unintended effects if plants are equipped with resistances that mean biodiversity is being damaged rather than protected.

With the Green Party and Social Democrats in lockstep on this issue, it’s likely the government will continue to rebuff new plant breeding technologies, insisting that they be stringently regulated like GMOs.

Organic NGOs bolster green rejectionism

Germany has an active organic food lobby that strongly opposes GE technology. Most anti-biotech NGOs view crop genetic innovation suspiciously, claiming it is masterminded by large corporations (although gene editing is so inexpensive it has spawned many entrepreneurial ventures globally) and is untested.

“Little is known about them from a health perspective, and from a technical standpoint they are obsolete,” claims Slow Food. “They have severe social impact, threatening traditional food cultures and the livelihoods of small-scale farmers.”

Save our Seed one of the most influential anti-GE NGOs, writes: “Save Our Seeds … advocates for a zero tolerance for contamination of seeds. Due to new developments in genetic engineering linked to the advent of CRISPR/Cas9, Save Our Seeds enlarged its focus and now also advocates for a GMO-free nature.”

Demeter, the Biodynamic Federation, says on its website that it “has always taken clear stand for a GMO-free agriculture by prohibiting any use of Genetically Modified Organisms…the precautionary approach to all changes made in our genetic heritage and planetary biodiversity is of primary importance. It is essential to ensure free access to genetic resources and to preserve genetic diversity for the future generations. The risks and threats inherent in GMOs are still relevant and high….”

According to IFOAM, Organics International, headquartered in Bonn:

As history has shown, promises of producers heralding GMOs and New Genomic Techniques as alternatives to pesticide-tolerant crops should be treated with caution. … Mere promises of expected benefits do not justify a weakening of the EU’s standards with regard to environmental protection and farmers’ and consumers’ choice.

In January 2022, the German government set an unobtainable goal of having thirty percent of all farmlands organic by 2030. Presently, 10.2% of all agriculture land is organic. Even the organic food industry acknowledges the target is unachievable.

Alexander Beck, Executive Director of the Association of Organic Food Producers, acknowledged these targets are more aspirational rather than realistic. “To grow, the sector needs an evolutionary development,” he said. “Producers would have to switch to organic production, while at the same time consumers have to follow this path…. These are all processes that, of course, take time.”

EU’s politicized interpretation of the Precautionary Principle

The biggest hurdle crop biotechnology supporters need to overcome is the tactical invocation of the ‘precautionary principle’ (PP) by opponents. The EU embraces a radical interpretation of the PP that theoretically rejects any innovation when the evidence is “inconclusive” whether it might be “dangerous”. That opens the door to blocking almost any new technologies, now and in the future.

The EU’s version of the precautionary is selectively and politically applied as many risky science innovations have been greenlighted including hardly-tested mRNA vaccines. It also rejects the seminal formulation of the 1992 Rio Declaration, agreed to by Europe, which states: “Where there are threats to serious or irreversible damage, lack of full certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation.”

Europe later turned its back on that clause, which opens the door to “cost-effective” solutions even when there is some uncertainty. It all but forecloses the use of a host of gene-edited products that could forestall and in some cases reverse the disruptions caused by climate change. And as the European Parliament has acknowledged, it is no riskier than traditional breeding; scientists have demonstrated that the laboratory process mimics what occurs in nature and poses no unusual risks. But facts and reason have not persuaded ideological critics.

Kevin Stairs, Greenpeace EU GMO policy adviser, sums up the current environmentalist position in Europe: “The EU Commission and national governments must respect the precautionary principle and the European Court of Justice’s decision – GMOs by another name are still GMOs, and must be treated as such under the law.”

Where do German scientists stand on new breeding techniques?

Irrational doomsday scenarios reflect a disdain for science. Contrary to what rejectionists want the public to believe, there is broad consensus in the global scientific community about the safety and effectiveness of GE crops.

The German science establishment agrees, endorsing both classic transgenic GMOs and newer breeding techniques. According to a joint 2019 report issued by The German National Academy of Sciences and Engineering, The German Research Foundation and The Union of the German Academies of Sciences and Humanities, EU crop biotechnology regulations should be revised …

… to exempt genome edited organisms from the scope of genetic engineering legislation if no foreign genetic information is inserted and/or if there is a combination of genetic material that could also result naturally or through traditional breeding methods.” … Further development of sustainable agriculture in Europe is considerably obstructed by the particularly restrictive, undifferentiated and time and cost-intensive approval processes for molecular breeding products. … The application of the precautionary principle must not be linked to speculative risks…the benefits of new molecular breeding methods and their products must be considered appropriately and, in a problem-oriented manner.

Medical genetic engineering is regulated differently than agricultural applications

As noted, there has been little controversy in Germany about using genetic engineering to create medicines and vaccines. BioNTech, headquartered in Mainz, in collaboration with Pfizer, developed the first mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in record time. BioNTech is also utilizing GE to develop treatments for cancer and infectious diseases, and to create vaccines for malaria and tuberculosis. The antagonistic targeting of GE technology for crops but not for medicine makes no intellectual sense, but opponents are not swayed by facts.

Based on recent statements by key government officials, there is no change in the Germany’s hostile attitude towards crop genetic engineering. “The approval procedure for GMOs from new genetic modification techniques must remain as strict as for other GMOs,” said a spokeswoman from the Ministry of Agriculture. “This means that we will adhere to an authorization process with a case-by-case risk assessment, a strict labeling requirement and traceability.”

Silvia Bender, State Secretary in the German Ministry of Agriculture, was equally blunt. “Deregulation [of GMOs from new genetic modification techniques] at the European level would run counter to consumer desires [of transparency and freedom of choice of food] and I believe we should not do that.”

Anti-GE sentiment merged with widespread suspicions about corporations are so embedded in the political and popular culture of Europe that it will be very difficult to dislodge no matter the potential benefits, as the Financial Times has noted.

Environmentalists and activists say agricultural companies have seized on climate change to foist untested technology on the public…. There is no reason to deregulate gene editing, says Mute Schimpf, food campaigner at NGO Friends of the Earth Europe. It is a new technology developed in the last 10 years. We don’t know how it might impact on nature, on agriculture and how the consumer interest will be affected.”

In light of the opposition towards genetic engineering of crops among many European politicians, it is unlikely there will be any substantial relaxation on the prevailing regulation in the near-term as it would unleash a hornet’s nest of protests. Top EU officials are still publicly signaling a ‘go slow’ approach.

“What we’re looking for is a proportionate risk assessment for the NGTs [new genomic techniques], so that means we wouldn’t do away with [precautionary principle-based regulations] altogether,” said Claire Baury, the EU official in charge of the regulatory proposal process for new genome technology.

To prepare the groundwork for a significant relaxation of the stringent regulations for NPBTs crops, the European Union would need to implement a robust education campaign to alter the status quo. It would need to convince a distrustful public that genetic engineering is essential to maintaining the competitiveness of EU agriculture, that it is safe for human consumption and in nature, and that it offers substantial environmental sustainability benefits. It would also need to confront the anti-GE disinformation campaigns that have been so successful in sowing public doubts about the technology.

If the EU leadership cannot muster enough courage to take on the green lobby, new breeding techniques will never gain widespread acceptance across Europe, and that will hurt EU consumers and Europe’s competitiveness in science and food innovation.

“We have to innovate if we want to produce food in Europe,” says Dutch farmer Hendrik Jan ten Cate, summing up the frustration of many supporters of biotechnology. “Maybe we will become dependent on other countries if we do not adopt these new technologies.”

Steven E. Cerier is a retired international economist and a frequent contributor to the Genetic Literacy Project