Tonight is the 85th anniversary of Kristallnacht, “The Night of Broken Glass.” On November 9 and 10, 1938, Storm Troopers, Hitler Youth and civilians rampaged throughout the German Reich, shattering the windows of more than 1400 synagogues and more than 7,500 businesses and Jewish homes. More than 400 people were murdered.

In the following days, in what the Nazi government called Judenakation (Jewish Action), the Gestapo arrested more than 30,000 Jews, herding them through the streets and then transporting them to concentration camps.

Three days later, in yet another gruesome twist, Hermann Göring, designated as Hitler’s successor, decided not only to fully “eliminate Jews from German economic life,” but to make the victims collectively pay 1 billion Reichsmarks for the damage inflicted on them.

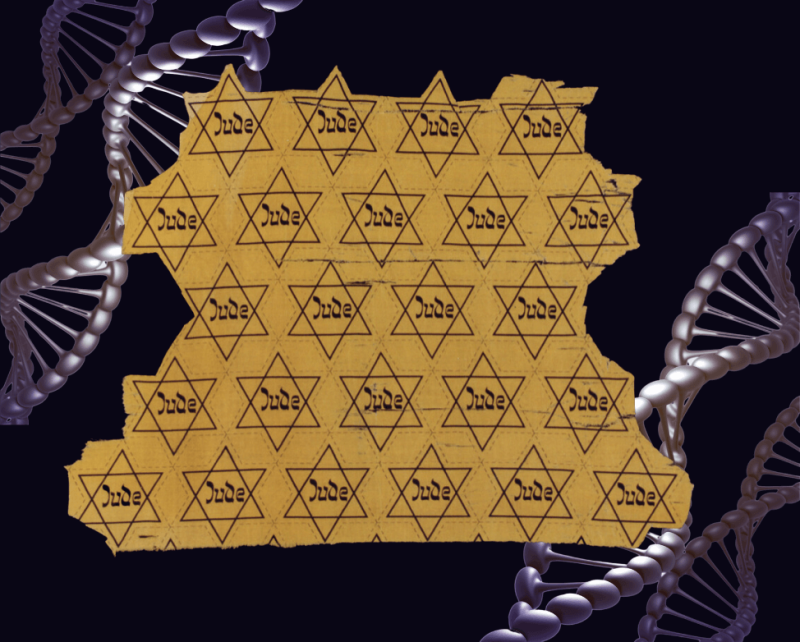

Nazi officials implemented the Star of David yellow badge to brand Jews as their master plan of elimination accelerated. Many date these horrific events as the formal start of the Holocaust.

The Holocaust that followed led to the coining of the phrase “Never again,” a commitment of Jewish resolve to never again allow the branding of Jews as “the other”.

That resolve is now being tested. As the Israeli-Hamas war rages on, advances in genetics are raising perilous questions about whether a new form of anti-Jewish branding could emerge.

DNA, ancestry and Jews

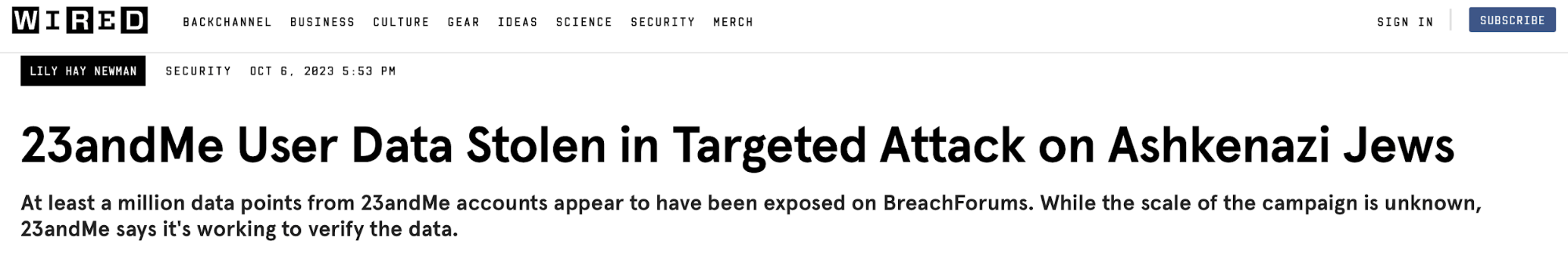

After World War II, antisemitism at times faded to a simmer only to resurge with targeted attacks, never really vanishing. But even with a surge of attacks on synagogues around the world since 2016, anti-Jewish hate seemed a fringe phenomenon. When I read an article in Wired, “23andMe User Data Stolen in Targeted Attack on Ashkenazi Jews,” I skimmed it, not too concerned. It was Friday, October 6.

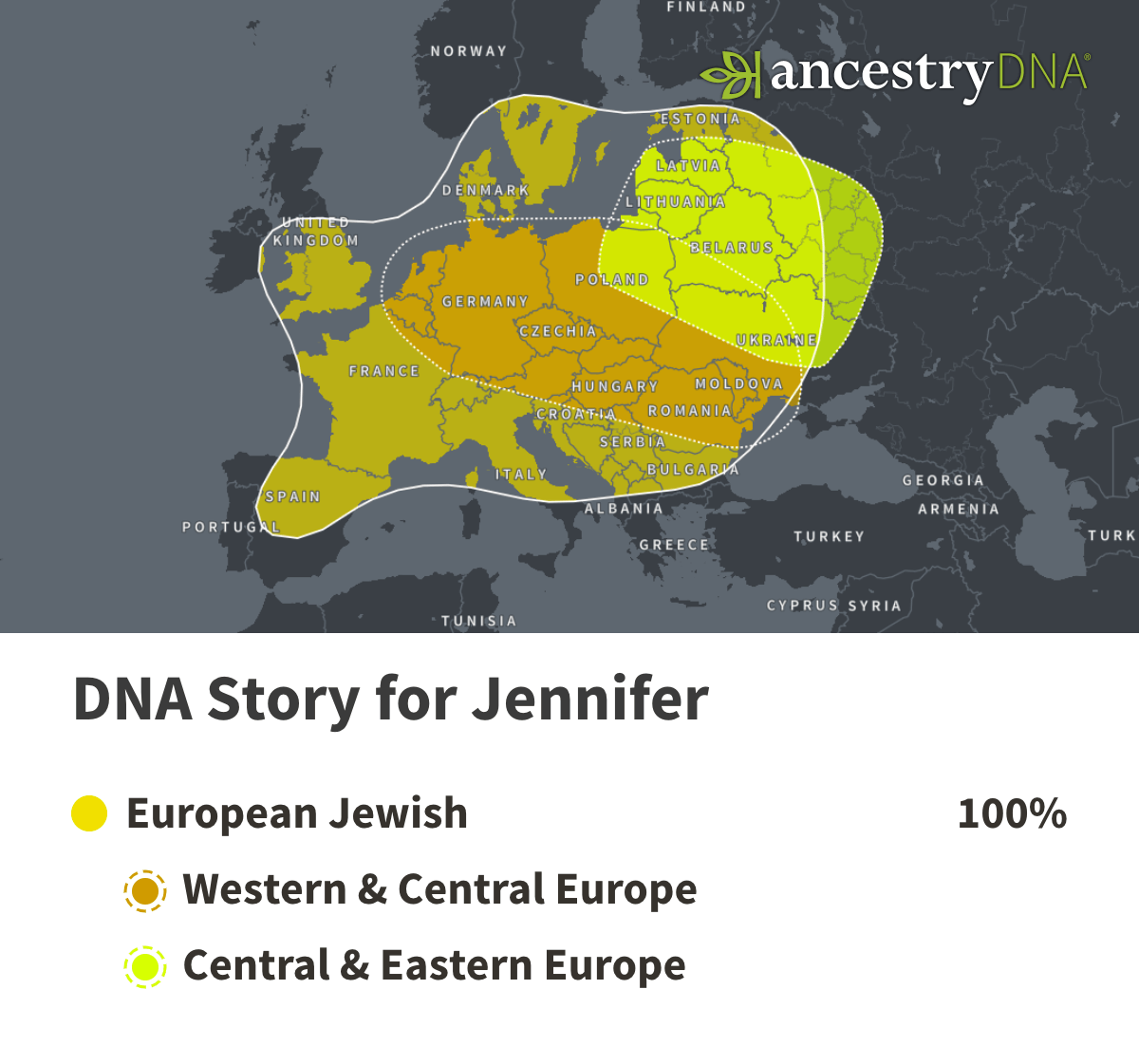

If anyone wanted to see my personal info at 23andMe — the map of eastern Europe and my 99.7% Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry or that I can taste asparagus, carry a tune and have more Neanderthal DNA than most customers — so be it.

But I felt differently the next day, Saturday October 7. In the immediate wake of Hamas’ attack on innocents in Israel, being identifiable as Jewish had become a risk. Were my consumer DNA test results akin to the yellow stars that Jewish people were forced to wear in Nazi-occupied countries during the Second World War?

DNA profiles of Ashkenazim are indeed strong identifiers, for we descend from Jews who trace their ancestry to the Levant (Egypt, Cyprus, Iraq, Palestine, Syria, Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey) during Biblical times. Many thousands migrated to Italy and then to Central Europe, with the men often taking on non-Jewish wives.

After an unending undulation of small population bottlenecks during the first millennium that serially strangled the diversity of our gene pool in a continual choreography of hatred, the majority of surviving Jews settled in Eastern and Central Europe. Known as Ashkenazim, they went through at least one “genetic bottleneck” by 14th century, whittling the population to only a few hundred individuals. It then grew slowly for centuries and then exponentially from the 18th century onward.

All present-day Ashkenazi Jews can be traced back to this small population. Over the centuries, Jews have been periodically blended in or co-existed peacefully with local populations or viewed as a separate ‘race’ and an object of hate. We are now seeing the flames of antisemitism reignite at universities and public protests across the US, Europe and elsewhere, with Jews globally viewed as proxies for Israel.

It’s uncomfortable to acknowledge this in the current atmosphere, but Ashkenazi Jews, although not a ‘race’, are identifiable by genetic signatures and so-called Jewish diseases, the legacy of intermarriage among our clan dating to the Middle Age bottleneck. I can’t imagine exactly how consumer DNA data from Jewish people might be misused, but being so identifiable is concerning. And while recent legislation oversees use of consumer DNA data in law enforcement and life, long-term care, and disability insurance, it doesn’t go far enough to consider genetic privacy and hate crimes.

Attack and hack? 23andMe alerts consumers

On October 12, a generic email from 23andMe came:

Dear Ricki,

We recently learned that certain profile information — which a customer creates and chooses to share with their genetic relatives in the DNA Relatives feature — was accessed from individual 23andMe.com accounts. This was done without the account users’ authorization. We do not have any indication at this time that there has been a data security incident within our systems, or that 23andMe was the source of the account credentials used in these attacks.

This missive went on to explain that customers using the same password for different things could have faciliated the breach, so we were admonished to change passwords and enable multiple-factor authentication. “If we learn that your data has been accessed without your authorization, we will contact you separately with more information,” the email said.

In the next few days, as details emerged of the massacre at the Nova music festival, 23andMe’s initial email that “certain profile information” had been breached became more specific: the customers are of Ashkenazi Jewish heritage.

Me.

I got no further information, even at 23andMe’s blog. Their most recent news release, pitches the new “23andMe Health Membership“ of “customized action plans, from recommended lifestyle changes to clinician-ordered lab tests.” Christmas and Hannukah are nearing, and kits must be sold, the website already festooned with ads for the holiday.

Was the timing of the 23andMe hack targeting private genetic data of Jews, just prior to the two-years-in-the-making October 7 attack by Hamas, a coincidence? Perhaps not.

The Wired report had details:

Hackers posted an initial data sample on the platform BreachForums earlier this week, claiming that it contained 1 million data points exclusively about Ashkenazi Jews …. On Wednesday, the actor began selling what it claims are 23andMe profiles for between $1 and $10 per account, depending on the scale of the purchase. The data includes things like a display name, sex, birth year, and some details about genetic ancestry results … like that someone is of ‘broadly European’ or “broadly Arabian’ descent. The information does not appear to include actual, raw genetic data.

Even raw genetic data would be meaningless. It’s just a collection of spots —“data points” — in a genome where the DNA base varies in populations, not sequenced genes or anything about traits or health. The colored maps from 23andMe and Ancestry come from a million or so points (SNPs, for single nucleotide polymorphisms) and match the patterns to those from the ancestral peoples of nearly 2,000 populations.

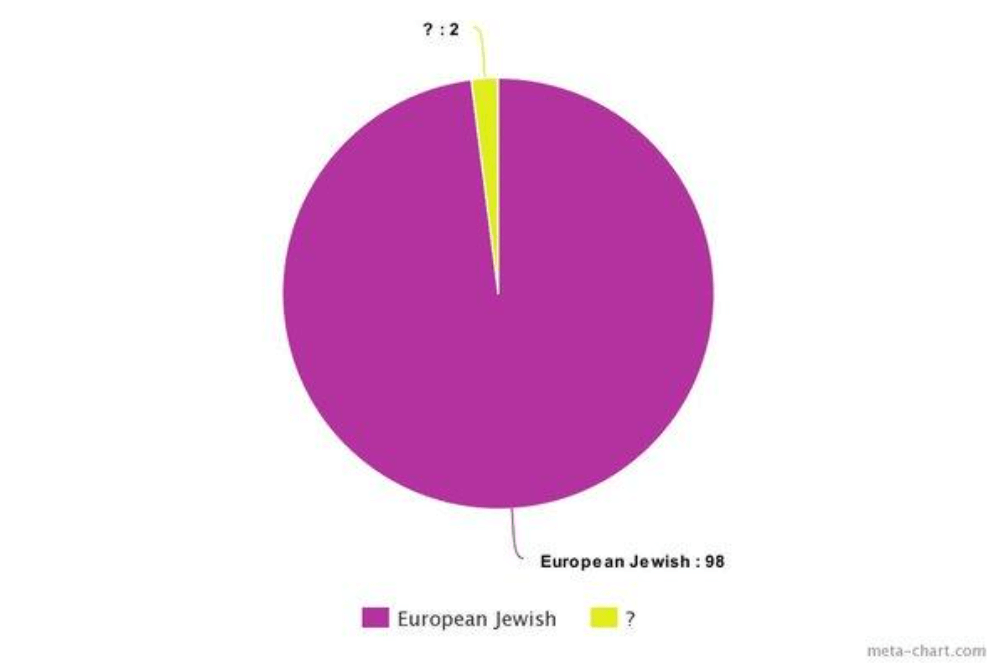

Most of us Ashkenazim are probably sixth cousins or closer. Our data are boring! We’re most recently from Ukraine, Poland with its fluid borders, Lithuania, elsewhere in eastern Europe. Comedian Modi Rosenfeld summed up his disappointing experience with consumer DNA testing:

I got back the results, and they have these amazing pie charts. One-eighth Navajo Indian! A quarter Iberian! Celtic, Norwegian, African, I was so excited for mine! I opened mine up: 99.8% Jewish. That was it. No Vikings, no Navajo, no nothing. The pie chart was a matzoh ball with a toothpick in it.

But it is that sameness, the near 100% identity on a genetic level, that’s terrifying, that evokes the image of yellow stars used to identify Jews in Nazi Germany.

Broaden DNA privacy laws?

Ironically, also on October 31, The Journal of the American Medical Association published a viewpoint, “The Genetic Information Privacy Act: Drawbacks and Limitations.” Anya E. R. Prince, JD, from the College of Law, University of Iowa, Iowa City, discussed the Genetic Information Privacy Act bills under consideration in 26 states over the past three years. Their aim was to protect genetic privacy for consumer DNA testing results used by law enforcement and insurers.

Eleven states have adopted the laws, with bipartisan support. “However, the public should not be fooled. Even though the bills do offer sensible and important protections, they miss the mark at fully addressing many genetic privacy concerns held by the public and many in the medical and research fields,” Prince writes.

One that the laws clearly miss is misuse of genetic information to identify members of a group to perpetuate hate crimes.

Given the schedule of journal publishing, Prince likely wrote her Viewpoint well before the events of October 7, and so it doesn’t cover this new kind of nefarious uses of DNA data.

Existing protection against use and misuse of genetic test results, from the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008, covers clinical tests. GINA prohibits employers from using genetic information to hire, fire, or promote an employee or require genetic testing, and health insurers can’t require genetic tests nor use results to deny coverage. The law clearly defines genetic tests – DNA, RNA, chromosomes, proteins, and metabolites – and genetic information – genetic test results and family history of a genetic condition.

But the year of GINA’s debut is critical: 2008. That’s when consumer DNA testing began. I was at the human genetics meeting where it was introduced to an initially highly skeptical audience of scientists and physicians. I don’t think they, or the founders of the companies, imagined how eager people would be to spit into tubes or swish their cheek linings to learn about their DNA.

In contrast, the new Genetic Information Privacy Act covers direct-to-consumer DNA testing and emphasize consent of the individuals who provide DNA samples for how the data are used. It cites two applications: law enforcement and insurance.

According to the new laws, testing companies must follow “valid legal processes” that include consent when providing DNA data to law enforcement agencies. However, Prince points out that these “processes” are not defined. Plus, some consumer DNA testing companies already require such consent, so it clearly isn’t sufficient.

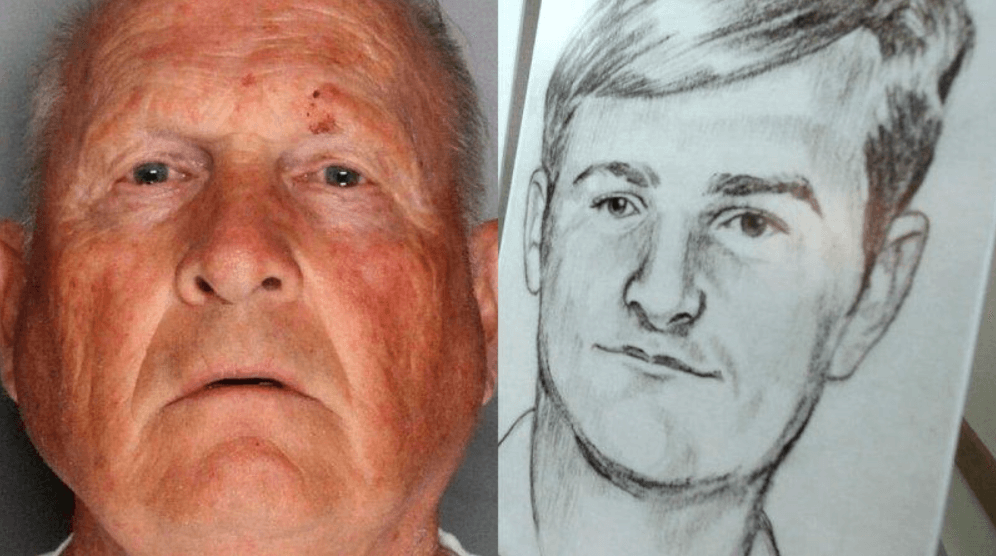

At issue is familial DNA matches — using DNA data from someone in prison who shares genetic markers with a relative who is a suspect known from DNA found in evidence. That’s how the Golden State Killer was identified.

On the insurance front, since 2021, 29 bills in 16 states have proposed consent to use consumer DNA test results in considering life, long-term care, and disability insurance.

University of Iowa College of Law professor Anya E. R. Prince’s conclusion is both prescient and chilling:

Although a groundswell of states passing a Genetic Information Privacy Act seems like a consumer win, the sweeping name should not obscure the fact that most of the laws passed at the state level only add minimal protections focused on consumer consent, transparency, and internal data handling. The enacted legislation does not robustly address the fact that third parties, particularly law enforcement and insurers, can still access and use consumer genetic data.

Coda

Being Jewish this time of year, especially if you live in a nearly-100-percent Christian town like I do, can be tough. That you celebrate Christmas is assumed. Years ago, well-meaning people would ask my kids what Santa was bringing them, and when they answered nothing, were lectured for “being bad.” Public school had Christmas gift exchanges; school photos were taken on Yom Kippur. Today, I leave dance classes when the Christmas music is unending.

But being marked as Jewish by my DNA is different. Sometimes it’s better being invisible.

Even if nothing comes of the 23andMe DNA data breach, the possibility reawakens the never-very-far-away collective familial memory of what happened to our ancestors in Eastern Europe and of the lucky ones who escaped the mass annihilation of the Pogroms leading up to the Holocaust. For we always know that it can happen again.

Ricki Lewis is the GLP’s senior contributing writer focusing on gene therapy and gene editing. She has a PhD in genetics and is a genetic counselor, science writer and author of The Forever Fix: Gene Therapy and the Boy Who Saved It, the only popular book about gene therapy. BIO. Follow her at her website or X @rickilewis