This raises two problems, in the eyes of other scientists: one is that the immunologist hasn’t offered up the results of her study for peer review or critical evaluation by other specialists in the field — there is no published paper. The second problem is that going to national media with sensationalist claims is not without consequences.

Shortly after the piece was published in O Estado, Brazil’s Attorney General’s Office has seen a number of cases based on the information published. And it is understandable: in fact, such a claim, if based on good science and solid data, would demand not only a broad reform in agriculture—on a global scale—but also of all toxicology as a scientific discipline.

But, is the science good and the data solid? Honestly, nobody knows. The author did not submit her results for peer review, has briefly commented on the methodology in the news piece, and seems to expect that we take her word for it. She also did not answer requests by other scientists (including yours truly) for her to release her data for independent analysis.

In principle, no researcher is obliged to share raw data, but refusing to do so is rarely favorable. Many scientific journals require data as a prerequisite for publication.

That said, the dearth of information available about the study described in O Estado, in addition to an understanding of fundamental science on the subject, suggests that any firmer conclusion that may be sought from the work—in case one day it be made public—will be, to be generous, highly questionable.

Beyond the scientific considerations, the credibility of the study’s results is damaged further by the fact that the researcher chose to present her findings in the media and thus to an unspecialized audience instead of submitting it for review by specialists.

Historically, this has been the hallmark of pseudoscientific proposals. Immanuel Velikovsky’s theory that the planet Venus might be a fragment ejected from Jupiter was published in a book aimed at the general public after being rejected by physicists and astronomers; and in a similar case, in 1989, chemists Martin Fleischmann and Stanley Pons introduced their “cold fusion” process in a press conference before submitting the technical details for peer review.

UPDATE: About 24 hours after the original publication of this article, the researcher took to social media to explain her position regarding the release of her data and defend the findings of her research. The video with Monica Lopes-Ferreira’s statement can be seen in full here.

The Dose Makes the Poison

At approximately the same period when the Portuguese arrived in Brazil for the first time, Swiss physician Paracelsus stated the principle that “everything is poison, and nothing is without poison: only the dose makes the poison.” The statement is generally boiled down to “the dose makes the poison.” Paracelsus’s principle remains valid to this day. Some substances are harmful in very small doses such as botulinum toxin. A small dose of this bacteria-produced substance can be lethal. However, even smaller doses are safely used in medicine.

Therefore, claiming that there is no safe dose of a certain class of molecules, a class that “coincidentally” corresponds to synthetic molecules used in agriculture, is at least an implausible and at most a dangerous generalization. It’s dangerous because the population and authorities take science and scientists seriousl. Healthy respect for science in the public sphere has brought us, among other things, vaccine campaigns, basic sanitation works and rules for preserving the environment.

Abusing this respect to present the public with catastrophic allegations can lead to unnecessary fears and expensive and inefficient, if not disastrous, changes to public policies. In the long term, attitudes like these can undermine the very ability of science to be heard in raising legitimate alarms, when necessary.

The Details

Even if we consider a statement like “there is no safe dose of agrochemicals” was just an exaggeration by the media, a figure of speech (even though the researcher did not show any reserve when uttering it), we catch a glimpse of several technical problems in the little we know about the study. It is worth repeating that an adequate and complete scientific critique depends on publishing the original material and transparency of the data, which so far has not occurred.

Monica Lopes-Ferreira said that she conducted a study commissioned by the Ministry of Health that was forwarded to Instituto Butantan at the request of Fiocruz, to test the toxicity of ten common pesticides in Brazil using a zebrafish [Danio rerio] experimental model.

Zebrafish has been used as an animal model in toxicity studies on reproduction, embryonic development and other tissues.

The alleged research study—”alleged” because there are no published findings, not even in an official report to Fiocruz or the Ministry of Health—is said to have evaluated the survival and behavior of fish embryos and of the fish themselves exposed to agrochemical concentrations recommended by ANVISA. We know very little about these concentrations, since there is no data about them available.

In Estadão, the researcher says that she used the minimum concentrations of 0.22mg/mL (or 22mg/L) for Glyphosate, Malathion and Pyriproxyfen, which according to her, should be inoffensive but killed all the embryos.

This information is problematic, though. Take glyphosate for example: there are published studies that show that half of the stated concentration alone is toxic for zebrafish. This study—published in a peer-reviewed journal—carried out by a group at the University of Exeter in the United Kingdom, identified 10mg/L as being the minimum dose that causes death and/or aftereffects in embryos. The British team even made a caveat that it was an extremely high concentration, which would rarely be found in nature. The researcher at Butantan apparently worked with at least twice the known lethal dose and thought it to be low.

In order to better understand why this number does not match the existing literature, we need to understand a little bit about how a safe dose of something, be it a drug, a pesticide, a food or a cleaning product, is calculated.

The dose makes the poison (2)

First of all, it must be said that the “zebra”, to this day is not a model considered to be standard for determining food poisoning or medicines for these human beings. In order to do this, we use rodent and non-rodent mammals: i.e., mice, rats and dogs. And we calculate two basic indexes from which we can estimate final values. These are LD50, the 50% lethal dose and the acceptable daily intake (ADI).

First of all, it must be said that the “zebra”, to this day is not a model considered to be standard for determining food poisoning or medicines for these human beings. In order to do this, we use rodent and non-rodent mammals: i.e., mice, rats and dogs. And we calculate two basic indexes from which we can estimate final values. These are LD50, the 50% lethal dose and the acceptable daily intake (ADI).

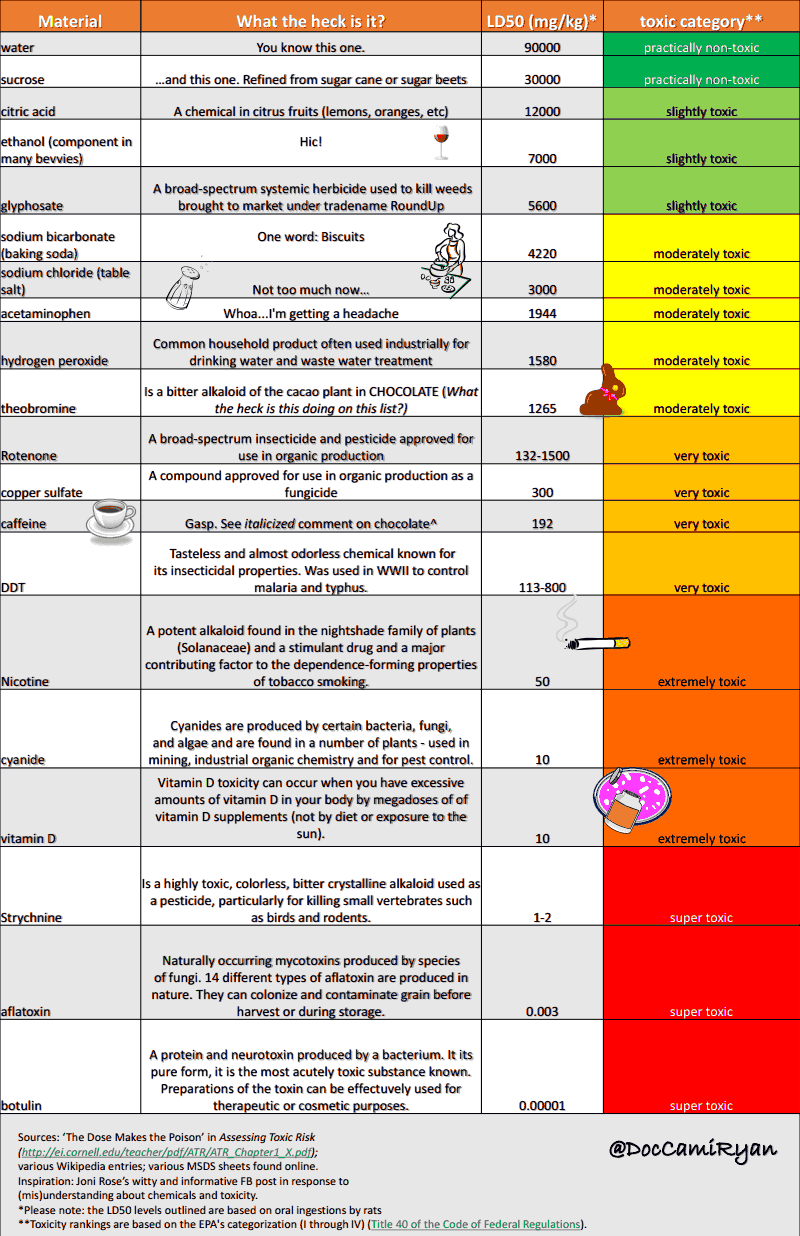

LD50 indicates the minimum dose in which half of the lab animals used in the study die. Thus, it serves to show what would be considered an acutely dangerous dose. This measure defines an amount that would have to be consumed in one sitting to cause death, and not “in batches.” That is the amount that we need to know when defending the use of a product and someone, educated guesses aside, dares another: “why don’t you drink a cup of that stuff, then?” In general, “that stuff” is not a drink and would never be consumed in one gulp, but if someone wanted to take the dare, it would be good to know about LD50. In the table below, we see the LD50 of several everyday products.

As can be seen, coffee is more dangerous than the feared glyphosate when discussing acute poisoning, right? And glyphosate is less toxic than acetaminophen (paracetamol) or even table salt. That does not mean that coffee is dangerous. Rather, it shows that to cause acute intoxication we need a lot more glyphosate than coffee or salt.

LD50, however, does not help us measure continued, long-term exposure. When we talk about pesticides, we want to know the risk we run from exposure over a lifetime. In the end, these products are present as byproducts in food.

In order to achieve this, we must determine the ADI (acceptable daily intake). ADI is calculated by submitting the lab animals to increasing concentrations of the chemical compound for a long period of time up to concentrations where the first adverse effect is observed. The largest dose that still proves to be innocuous is thus divided by a safety factor of 100. The result is the ADI, in other words, 1% of the maximum dose that did not bring about any detectable change in the lab animals.

And More Residues

In the case of agrochemicals, we have another measure of safety because we know, after all, that these products leave residues in the soil, which could contaminate water tables and the crops themselves, and make their way to our dinner tables in the form of fruit, vegetables and water with byproducts. The maximum residue limit (MRL) calculates the maximum permitted amount for each chemical product.

MRL calculations consider ADI and environmental factors and are different for each combination of product/pesticide. There is a certain variation in the rules adopted in each country, but there are international bodies like the WHO and FAO that establish recommended values. There is also the maximum permissible limits for drinking water. In the case of glyphosate, again, this amount is 500µg/L (0.5 mg/L) in Brazil, much lower than the concentrations used in the Butantan study.

Back to the Zebra

If we already have all this data on the toxicity of pesticides in humans, and we know what concentrations they are safe at, then why bother using zebrafish?

In the case of the study commissioned for Butantan, it is probably to measure embryonic development and to review environmental concentrations. Since we do not have access to the study’s data, it is hard to speculate whether the researcher used increasing concentrations of each product until she observed anomalies and, if that were the case, what anomalies they were; if there were some kind of more specific measurement performed with chromatography; what controls were used; whether the product evaluated was in its pure form or a commercial formulation, etc.

Professor Rafael Nóbrega from the Institute of Biosciences at Botucatu Campus of UNESP (State University of São Paulo) explains that you cannot estimate how much pesticide the fish absorbed. The proper way to do this would be to use analytic methods like chromatography after the experiment to determine how much of the compound was left. A study of the fish’s tissue could also be conducted. The author would have to show that in the article.”

However, as we have already seen, the declared doses, at least for glyphosate—just to stick to the same example—were double those observed to be the minimum for creating anomalies in the embryos. Another independent study showed that there was no change in zebrafish exposed to increasing concentrations of glyphosate up to precisely 10mg/L, and the authors concluded that the lack of toxicity, even in high concentrations, suggests that the herbicide is not harmful to the fish.

Rafael Nóbrega notes that in the British group’s study, even at the highest concentrations where only the parents were exposed, the embryos showed no anomalies. Changes only appeared when the embryos were directly exposed. According to him, this would be a relevant piece of information for extrapolating the findings to human health, for example. We also do not know whether this parameter was tested in the Butantan study.

A WHO report calculated the residual concentration found in fish exposed to the concentration of 10mg/L of glyphosate—again, half that used by the Butantan study—and found between 0.2 and 0.7mg/kg. This amount is at least twice the permissible amount of the ADI for humans (0.1 mg/kg/day). The same report shows that the higher concentrations of glyphosate found in the environment were 5153µg/L (5.2 mg/L) in lakes and rivers in Canada, but this was right after direct aerial application. The concentrations normally found in nature range from 10-15 µg/L, i.e., one thousandth of the minimum necessary for triggering anomalies in embryos.

According to Caio Carbonari, agronomist and professor at the School of Agronomical Science at UNESP Botucatu, the project undertaken at Butantan, as described in the press, does not make sense:

From a scientific perspective, its result is irrelevant regarding the risk analysis. The minimum concentration tested, right in the water, is 22ppm, or 22mg/L. This may seem low to people who do not work in this field, but it is a very high concentration! In what real conditions of use would we have such a concentration in bodies of water? Never.

He explained that the glyphosate is applied at an average dose of 1kg/hectare in agricultural areas over plants and soil. It does not stay or in soil, nor does it have motility, it quickly degrades. “The concentration used in the study is equivalent to spraying 440 kg of glyphosate directly into a 1-hectare pool, or 10,000 m2 large and two meters deep.”

Flavio Zambrone, doctor, former toxicology professor at the UNICAMP School of Medicine and president of the Brazilian Institute of Toxicology, also takes issue with the study, as it has been described:

The doses are very high, testing on fish and extrapolating to humans is a mistake. And fish are not the standard for tests in humans. In any decent toxicology test, there must be curve with different doses, starting with one where you do not find anything and ending with another where you find serious impacts. Without a dose that has no response, there is no way to evaluate which dose would be safe.

So, what conclusion can we draw about what has been published so far regarding Butantan’s experiment? Perhaps that we should not breed fish in aquaria saturated with pesticides. This is the conclusion that the government could have reached for free by simply using common sense, without consuming the meager funding for scientific research.

According to Décio Gazzoni, agronomist and researcher at EMBRAPA (Brazilian Agricultural Research Company) Soja, in his column in Portal DBO:

Analyzing the doses of pesticides used in the research mentioned above, the only conclusion possible is that we cannot breed fish in agricultural spray tanks, given the very high doses they used! One of the products, carbofuran, is banned in Brazil; bendiocarb has been ok-ed for use only as a household sanitary product. Besides this, the author claimed that both are in widespread use.

Angelo Trapé, doctor, toxicologist and retired UNICAMP professor believes that the researcher’s behavior was irresponsible. “Butantan does not have expertise in that area, I do not know why it was chosen to carry out that study. If she had used table salt in that concentration, she would have killed the fish. It is not that she displeased the Minister of Agriculture, she brought a finding that has no scientific basis. She is not being persecuted.”

Trapé was referring to the recent interview Monica Lopes-Ferreira gave to Agência Pública, where she alleges that she is being persecuted by her Institute and by the government due to the media coverage of the zebrafish case.

“I am not an irresponsible person. My father is a sugarcane farmer; if it were not for sugarcane, I would not have had an education, I would not be here. So, I know how important agribusiness and agriculture are,” she told Pública.

“The amount she used is not used in Brazilian agriculture. Even the population of farmers, who apply the pesticides, would never be exposed to those levels. I feel offended as a toxicologist and I repudiate the baseless sensationalist conclusion of this alleged study,” Trapé said.

In the current political situation in Brazil, where science is being attacked and its funding cut, it seems easy to sympathize with yet another researcher who says she is being harassed for spreading information that upsets the government.

The case of Ricardo Galvão, dismissed from his post at the head of INPE (National Institute of Space Research) for presenting data about deforestation that did not sit well with the executive in the Planalto, is still fresh in people’s minds. However, these two situations could not be any more different. The data that INPE provided was public: anyone can access it and it is under constant scrutiny by specialists in Brazil and abroad.

The data from the study at Butantan with zebrafish is still under wraps, far from public view and, most importantly, anyone who has the technical ability to evaluate them.

A version (in Portuguese) of this story originally ran at Revista Questão de Ciência and has been republished here with permission.

Natalia Pasternak is a researcher at the Institute of Biomedical Sciences (ICB) at the University of São Paulo – USP, and president of the Question of Science Institute in Brazil. Follow her on Twitter @TaschnerNatalia