This isn’t a hypothetical scenario; this is how Chile actually regulates the cultivation and sale of GMO crops, writes biochemist Daniel Norero:

On the one hand, the country provides R&D and multiplication services for GM seeds, and the countries that take advantage of and plant these seeds sell us the harvested grain for use in our food industry or animal feed. But Chilean farmers still can’t use the same technology for domestic/commercial purposes …. This situation leaves Chilean farmers at a disadvantage compared to their colleagues in the region, where six South American countries take advantage of bioechnology for commercial use.

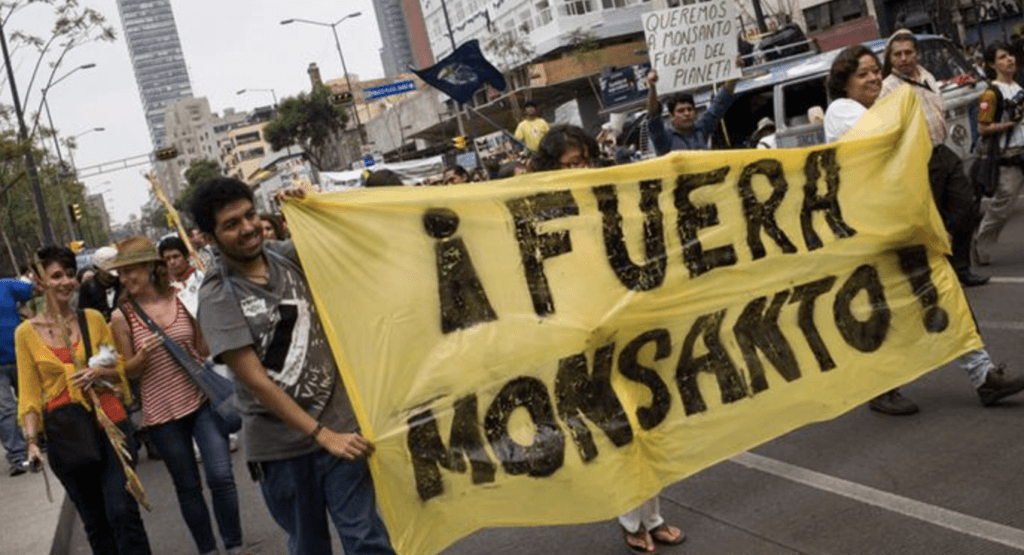

The country’s seemingly schizophrenic regulations reflect Latin America’s broader contradictory and confusing regulatory landscape. Despite high production levels of GMO crops in countries like Argentina and Brazil, adoption of agricultural biotechnology by other countries in the region like Ecuador, Bolivia and Peru has been slowed or, in some cases, prevented. This is all the result of a battle raging between the local scientific community and well-funded, international anti-biotech NGOs. The activity of these activist groups runs the gamut from infiltrating political and cultural institutions to bombing biotech research organizations, all of which has helped keep GMOs out of the hands of many farmers.

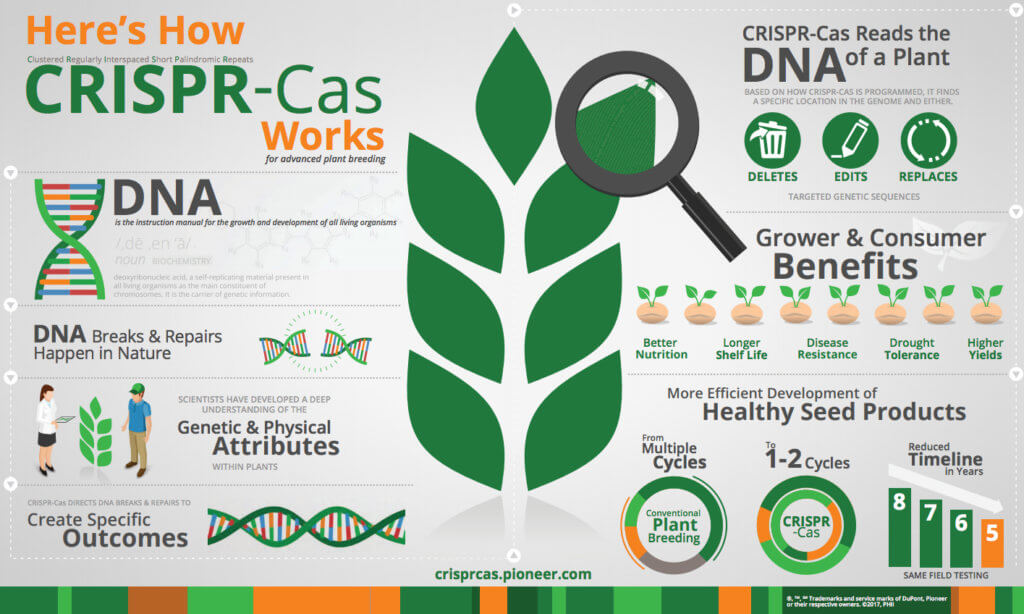

With the advent of new breeding techniques (NBTs) like CRISPR gene editing, this decades-long fight over access to agricultural technology is now entering a new phase in Latin America. Researchers have begun developing wide varieties of new and improved crops that typically contain no “foreign” DNA, unlike their GMO predecessors, and possess all sorts of novel, useful traits. Indeed, scientists in Latin America are using these breeding innovations to develop products specifically designed to meet the needs of consumers and farmers in the region. These crops include nutritionally improved “Golden Apples” and other fruit varieties that can withstand drought conditions and saline soils.

In the wake of these developments, activist groups are doubling down on their region-specific anti-GMO playbook, alleging that gene-edited crops represent a threat to Latin America’s cultural heritage. However effective this technology-stifling campaign has been in past years, it may very well fail this time around if scientists can learn to fight fire with fire by showing nations in Latin America how they stand to gain from these groundbreaking innovations in plant breeding.

The genesis of Latin America’s anti-GMO movement

Latin American (LATAM) countries have a shared history in which their indigenous communities remain culturally significant, which allows them to influence the political process where their territory, habits, and traditions may be compromised. In LATAM countries with onerous biotech restrictions and strong anti-GMO movements, indigenous communities, used and misinformed by activists, are the front line in the battle against genetic engineering. These communities contend that GMOs threaten their identity by allowing corporations to commercialize “Native foods without Free, Prior, and Informed Consent of Indigenous peoples who are the guardians of those foods,“ warns the pro-organic group Slow Food.

Such messages resonate with the citizens of Latin American countries, but they are ultimately hollow. According to Spanish biochemist JM Mulet, the campaign against GMOs is driven by ignorance, economic interests, and a desire for notoriety on the part of activist groups. NGOs, Greenpeace for example, initiate anti-biotech campaigns in countries where they’re most likely to succeed, based on careful “market criteria.” This is why the green group actively campaigns against GMOs in Latin America but says very little about their use in US agriculture, which remains the global leader in crop biotech research.

Greenpeace is not alone in Latin America, however. The region has become a hub of sorts for many high-profile activist NGOs working to establish restrictions on genetic engineering. The network includes:

Red por una America Latina Libre de Transgénicos (Network for a GMO-Free Latin America) based in Panama; Red de Acción de Plaguicidas (Pesticide Action Network) based in Chile; PROBIOMA and Fundacion Tierra (Earth Foundation) based in Bolivia; Union de Científicos Comprometidos con la Sociedad (Union of Scientists Committed to Society) based in Mexico; Red Guardianes de Semilla (Seed Guardians Network) based in Ecuador; Grupo Semillas (Seeds Group) and Biodiversidad LA (Biodiversity in LATAM) based in Colombia.

Activists level up: from the streets to government chambers

Anti-GMO activists have been present in Latin America since biotech crops first debuted in the region. Employing a diverse set of tactics, the movement has had a tremendous impact on its target audiences. It started in the streets, as most political movements do, attracting people to the anti-GMO cause with public presentations in iconic spaces to gain notoriety.

But in recent years, the environmental NGOs have shifted tactics in LATAM countries, using social networks and recruiting academics, singers, actors, and other influencers to disseminate their activist message. This effort paid off spectacularly by increasing the movement’s social recognition, allowing it to place leaders in key government positions. From these bureaucratic posts the activists have been able to enact severe restrictions on both GMO crops and the pesticides often used with them.

Genome editing in Latin America

With activist-friendly officials ensconced in powerful government positions, local scientists say, anti-GMO groups are expanding their mission to stem the spread of new breeding techniques like CRISPR by regulating them under existing GMO rules, the same tactic employed in Europe—where NBTs are effectively banned, for now. Replicating their European success will only be possible if the activists can obscure the crucial differences between GMO and gene-edited crops, grouping them together as “unnatural” and thus potentially harmful.

The existing GMO regulations in LATAM generally follow the guidelines established by the United Nation’s Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety, an international agreement designed to help policymakers “ensure the safe handling, transport and use of living modified organisms (LMOs).” Environmental groups are trying to use their considerable influence at the UN to include the products of novel breeding techniques under the UN’s existing GMO recommendations, even when these gene-edited plants can’t be distinguished from their conventional counterparts created through traditional breeding methods. Classifying gene-edited crops as GMOs gives anti-biotech officials in Latin America a justification to slap restrictions on plant breeding research and demand unnecessary safety testing of NBTs, putting gene-edited crops in regulatory limbo.

But there’s reason to believe Latin America will not follow in the EU’s footsteps. The Cartagena Protocol itself does not have the force of law. Each country has the autonomy to determine the legal status of genetically engineered crops in its territory, and so far several LATAM countries have said they will treat new gene-edited crops like conventional, non-GMO products unless they are transgenic (contain “foreign” DNA from other species).

If this tendency continues, it is possible that gene-edited products may be treated much more favorably than the transgenic crops that came before them. The political battle continues of course, but there is no doubt that a harmonized regulatory framework in the region will facilitate the adoption of enhanced crops, creating opportunities for these nations to increase their contribution to the global economy. Chile, for instance, is one of the biggest apple exporters in the world. If local scientists can commercialize the CRISPR-edited, nutritionally enhanced Golden Apple they’re developing, the nation’s economy stands to benefit in a big way by offering the world a desirable product no one else offers.

Genome editing: a new challenge for science communication

New genome-editing techniques are more precise tools from a scientific perspective, and they have seemingly limitless applications. But from a science communication standpoint, these tools present an enormous challenge, because they’re more difficult to explain to the public and policymakers—a fact activist groups have taken full advantage of as they attempt to conflate GMO and gene-edited crops.

For every innovation scientists develop, communication efforts that facilitate public understanding and trust are crucial to realizing the full benefits of that innovation. It is therefore vital to effectively communicate to the public, policymakers, farmers, and regulators the real impact of new breeding techniques.

Luis Ventura is a biologist with expertise in biotechnology, biosafety and science communication, born and raised in a small town near Mexico City. He is a Plant Genetic Resources International Platform Fellow at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. Follow him on Twitter @luisventura