Americans who shop at Whole Foods no doubt find such an argument compelling. But as an agricultural scientist, I know that banning GM crops because we have “enough food” papers over the real problems that biotechnology helps solve. This isn’t academic speculation on my part. My native Mexico, under the influence of anti-GMO groups, has moved ever closer to outlawing GM crops—and the result has not been more “food sovereignty” or security. Instead, Mexican farmers are losing their incomes, researchers are leaving the country and consumers are paying more for less food.

Mexico: A biotech “pioneer”

Mexico has been recognized as a crop biotechnology pioneer in Latin America for several decades. Shortly after the techniques to genetically modify plants were developed, Mexican scientists began putting them to use in their laboratories and a regulatory framework was established to ensure that farmers could safely cultivate GM crops.

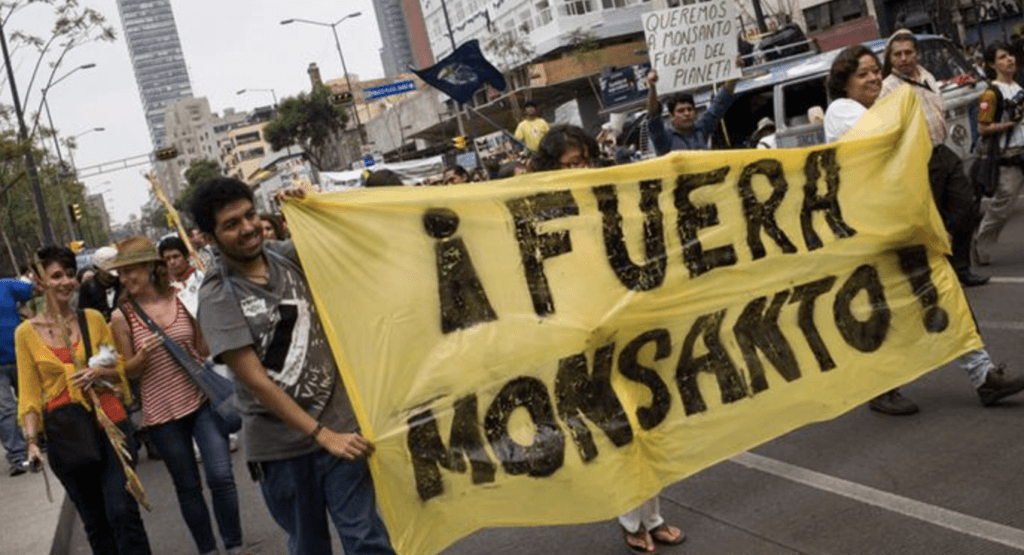

Sadly, much of this progress has been undone by committed anti-GMO activists who have abused the legal system and recruited like-minded political figures to enact policies that deny farmers access to important biotechnology innovations. So far, these efforts have led to the suspension of GM soybean and corn cultivation throughout Mexico, and a significant reduction in GM cotton planting, which began when regional regulators started rejecting or delaying all new permit applications for GM cotton.

Seven years of GM corn restrictions

In September 2013, a coalition of anti-biotech groups filed a class-action lawsuit to stop the Mexican government from granting permits that would allow farmers to plant GM corn. The ruling has since stopped the cultivation of and research on GM corn, severely affecting Mexican food producers and consumers. Mexico now depends on imports of corn for animal feed from the United States, Argentina, Brazil, and South Africa—all of which grow GM corn—and this competitive importation policy is crucial to protect Mexican consumers from higher meat, dairy, and poultry prices that can result when corn is imported from one country.

Critics may retort that the lawsuit was necessary because corn originated in Mexico and the country is home to many natural varieties of the crop. It’s vital that we protect this precious genetic diversity, the argument goes. This was a valid concern when Mexico’s biosafety law was debated, which is why the Agreement to Determine the Centers of Origin and Centers of Genetic Diversity of Corn was enacted. The law forbids the use of GM corn seed in eight northern Mexican states as a precautionary measure. But after the class-action suite in 2013, GM corn cultivation was forbidden in all 32 Mexican States without any justification. How did such a nonsensical proposal become official policy?

The anti-GMO movement infiltrates Mexican politics

Corn is a symbol of Mexico’s heritage, a deeply embedded element of its national identity. Anti-GMO groups have ingeniously capitalized on the crop’s cultural significance by couching their anti-science agenda in nationalistic rhetoric about protecting native maize. Government officials opposed to biotechnology have recently adopted this messaging as well.

GM crops threaten to “contaminate native strains of the grain and harm biodiversity,” the public was warned in the run up to the lawsuit. And that was just the beginning. “Elevated insect mortality” associated with GM corn would jeopardize pollinators, and farmers would become dependent on multinationals corporations—a concern not shared by most of Mexico’s farmers, interestingly enough.

Nonetheless, the activists behind this rhetoric have been very successful under recent presidential administrations, increasing their influence and control over the country’s agriculture policy. During the administration of President Felipe Calderon in 2009, changes to Mexico’s biosafety law allowed biotech crop developers to experiment with GM corn trials in approved regions in Mexico. Dozens of new permits were considered, but when Calderon left office, large-scale GMO corn plantings were delayed.

Later, during Enrique Peña Nieto’s administration, anti-GMO activists led by Fundacion Semillas de Vida (Seeds of Life Foundation) and Union de Cientificos Comprometidos con la Sociedad (UCCS) initiated the class-action suite to prohibit GM corn cultivation. The former leaders of these NGOs now occupy key strategic positions in the federal government. Elena Alvarez-Buylla, former Director of UCCS, now heads up the Ministry of Science (CONACYT), and the former leader of Seeds of Life runs the Primary Sector and Natural Resources office of the Ministry of the Environment.

Both administrators now lobby to protect the GM maize restrictions they won in court and advance other anti-science measures, such as limiting biotech cotton approvals and restricting imports of the weedkiller glyphosate, now widely used in Mexican agriculture.

A ban that blocks national research

The NGOs behind the lawsuit and subsequent ban wanted to get multinational seed companies like Monsanto (now owned by Bayer) out of Mexico, though again farmers wanted access to their products. But the activists also stalled public-sector biotechnology researchers who were close to developing GM maize strains tolerant to drought and frost, and other varieties that require fewer herbicide and fertilizer applications. The environmental groups therefore blocked research designed to help farmers protect the environment, including Mexico’s diverse selection of native corn varieties, the journal Nature reported in July 2014:

“These researchers complain that the lawsuit threatens to derail work that could boost maize yields, reduce imports and help to protect against threats such as climate change. ‘We are very frustrated, and there is a general sense of despair,’ says Beatriz Xoconostle, a plant biotechnologist at the Center for Research and Advanced Studies (Cinvestav) in Mexico City who leads a project to develop drought-tolerant GM maize. ‘We have been unable to accomplish our objectives.'”

Some researchers have given up and left the country. Luis Herrera-Estrella, a genomics researcher at the Center for Research and Advanced Studies of the National Polytechnic Institute (CINVESTAV), decided to move his research to Argentina where the regulatory requirements are “more science-based and sensible.” Remaining in Mexico would have meant meeting more than 100 requirements before obtaining a permit for experimental planting, “making the process unaffordable” and thus effectively impossible.

A GM solution to Mexico’s “water debt”?

These regulations handicap farmers by denying them access to technology, and ultimately force consumers to pay more for food. But they may also have more immediate political consequences. Due to northern Mexico’s dry climate, extensive irrigation is essential to maintaining food production in the region. However, an agreement with the US requires that Mexico pay its neighbor to the north a “water debt” that could jeopardize the water access of farmers in northern states like Chihuahua, one of the country’s biggest agricultural producers. The threat is so serious that growers have protested, even to the point of violence, because repaying the debt could kill their crops and cost them their livelihoods.

Alejandra Agreda, another researcher at CINVESTAV, developed a maize variety designed to withstand drought conditions and low temperatures, with northern Mexico’s difficulties in mind. After years of research, the enhanced corn seed is ready for commercialization, but because of the current restrictions on GM corn cultivation, this crop variety remains locked in the laboratory.

The same technology can be replicated in other crops, making it a potentially powerful ally to many farmers facing climate change, the effects of which are likely to get worse every year. By placating anti-GMO groups, then, Mexico’s government is exacerbating an environmental emergency that’s quickly escalating into violent conflict.

Fulfilling campaign promises

These actions aren’t surprising. The current administration is simply making good on its campaign promises, progressing towards a ban on GM crops as a way to achieve national “self-sufficiency,” protect native maize and the broader environment. Aside from the fact that GM crops pose no threat to Mexico’s heritage or environment (they benefit both), other programs implemented by this government undermine it’s pro-environment credibility.

The administration is building a 960-mile railroad through the Yucatan Peninsula, “where a significant part of the country’s biocultural heritage is found and where indigenous and peasant communities live.” Since taking office in 2018, President Andres Manuel Lobez Obrador (AMLO) has also cut subsidies to renewable energy projects and funneled the money into Mexico’s national oil company.

Such inconsistency suggests that AMLO’s publicly expressed concern for the environment and Mexico’s indigenous heritage isn’t all that genuine; instead, the administration appears more interested in winning key constituencies in the mid-term elections, even if it means contradictory policies on sustainability and cultural preservation.

Presidential decree to ban GM maize on the horizon

The situation in Mexico is likely to get worse, unfortunately. At the beginning of September, Victor M. Toledo, a well know anti-GMO activist and then head of the Ministry of Environment (SEMARNAT), resigned his position. But his final act before stepping down was to announce that AMLO is poised to ban transgenic maize from the country, including both imports and cultivation.

According to specialists, this measure is impractical and even harmful. To say nothing of the trade conflict it could spark with the US, which exports 20 million tons of GM corn to Mexico annually, the ban would drastically cut the supply of an essential cereal to Mexicans. That would increase the price of all corn-based products (the foundation of Mexican cuisine), and create food shortages in some parts of the country.

So before anyone else insists that GM crops don’t improve food security, I invite them to visit Mexico and see how anti-GMO activism has affected my country. There’s some frustrated farmers and scientists who will gladly show them around.

Luis Ventura is a biologist with expertise in biotechnology, biosafety and science communication, born and raised in a small town near Mexico City. He is a Plant Genetic Resources International Platform Fellow at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. Follow him on Twitter @luisventura