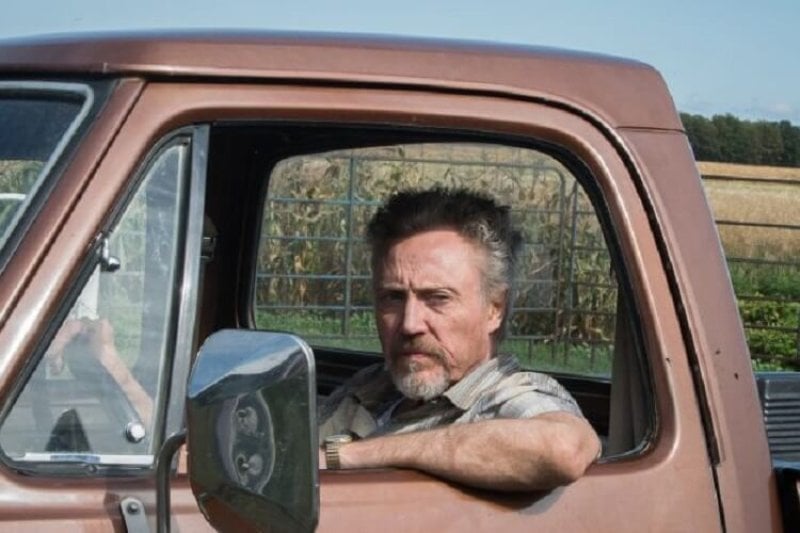

Simply titled “Percy” and starring Hollywood A-lister Christopher Walken, the film’s plot goes something like this: 22 years ago, in a classic case of David vs Goliath, biotech giant Monsanto wrongly sued blue-collar Percy for patent infringement. Schmeiser’s only crime was owning a field that was accidentally contaminated with the company’s herbicide-tolerant, genetically modified canola. Never afraid of a noble fight, the fiercely independent family man and farmer battled his way up to Canada’s Supreme Court, defending his property rights against unjust infringement by Big Ag and their duplicitous lawyers. He ultimately lost his legal battle, but Schmeiser reminds us why it’s vital to stand up to corporate bullies in our pursuit of a better world.

[Editor’s note: This is part one of a three-part series on Monsanto’s seed patent legal battles. Read part two and three.]

The film hit Canadian theaters just before the real Percy Schmeiser died peacefully in his sleep at 89 on October 13, after a long battle with Parkinson’s disease. It may seem ungenerous to take a man down a peg while his family mourns and his legacy is burnished by Hollywood. Ungenerous perhaps, but necessary. The occasion of his death and the film’s release call for an exposition of the facts of the case, which has been transformed into a folk-hero story and amplified by anti-GMO activists for two decades.

The making of a folk hero

Percy Schmeiser was a Canadian canola farmer who was sued in 1998 by the seed and chemical company Monsanto (now part of Bayer) for illegally replanting biotech canola seed that the farmer was not licensed to use. It’s easy to understand why these events have been misconstrued over the years. We all know the contours of a good David vs. Goliath story. David is supposed to be righteous. Goliath is supposed to be unreasoning and greedy, imposing his will by dint of his size.

If David isn’t righteous and Goliath isn’t unreasoning, we tend to reshuffle aspects of the story and sand off some rough edges, which is precisely what Hollywood did to make this film. Percy isn’t in any theaters where I live; they are all closed due to the pandemic, but I reached out to the production company to see if I could get a screener for review and never heard back. Nevertheless, from the trailers and pre-release reviews, it’s clear the film tells the story from Schmeiser’s point of view and takes him at his word. “I believe every word Percy said,” director Clark Johnson told CBC News. “I wouldn’t have took on and told the story if I didn’t believe it.”

What do farmers think of “Percy”?

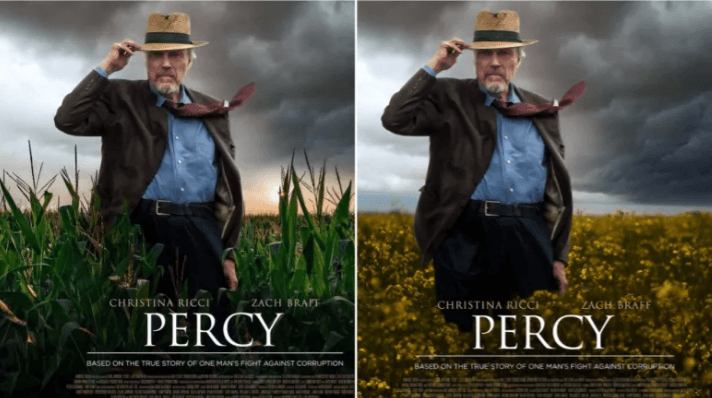

Farmers and the farm press haven’t been as enthusiastic as Johnson. They were quick to point out that the original movie poster featured Christopher Walken as Percy, a canola grower, standing in a cornfield.

The production company fixed the poster, but farmers and the farm press had more pressing concerns. Speaking with CBC, one farmer noted that the film amplified a distinctly anti-GMO and scientifically dubious message:

“Is that what the bent of this movie is going to be? Is it going to be all about anti-GMO?” said Todd Lewis, a canola farmer from Gray, Sask. He said anti-GMO activists hijacked Schmeiser’s plight long ago and said many farmers are nervous about that storyline.

“Farmers are comfortable with GMO,” said Lewis, president of the Agricultural Producers Association of Saskatchewan. “GMO is sound science …. it’s been proven safe again and again.”

The editorial board of Western Producer, a regional farm press publication based in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada, wrote:

Hollywood tells some interesting tales. Some are based on true stories. Others, such as the soon-to-be-released move entitled Percy, appear to be based on untrue stories loosely connected to events …. The movie will likely aid public misunderstanding of modern plant breeding, farmers’ and breeders’ rights to seed, genetic modification and glyphosate ….

In the post-courtroom world, Schmeiser became a hero of the anti-GM …. crowd and was paid to travel the world telling his version of events. Like this new movie, that version differed from the one the courts heard and ruled upon …. “On the facts found by the trial judge, Mr. Schmeiser was not an innocent bystander; rather, he actively cultivated Roundup Ready canola.”

Monsanto Canada Inc v Schmeiser: the real story

As often happens with complex, emotionally charged stories, the facts surrounding Schmeiser’s legal battle with Monsanto got lost in translation once the press began covering the trial. In March 1999, about seven months after the biotech giant filed its lawsuit, the case was widely characterized as an example of accidental contamination or cross-pollination. British newspaper The Independent reported at the time:

FARMERS WHO find that stray genetically modified seeds have blown on to their land from neighbors’ fields and then taken root could face massive fines if the agrochemical giant Monsanto wins a test case in a Canadian court …. [T]he company claims that the patent on its genetically modified (GM) seeds has been violated. GM canola (rape) plants from Monsanto seeds were found growing among [Schmeiser’s] crops. The farmer believes that the seeds blew on to his land.

And that’s how it has been widely characterized ever since. But that isn’t what the case was about, or the legal precedent it set.

The year was 1997 and Monsanto’s first generation of herbicide-tolerant crops had just hit the market a few years earlier. Corn, soybeans, and canola had been bred through genetic engineering to survive exposure to the herbicide Roundup, allowing for markedly more efficient weed control than what had come before.

The seeds for those crops came with a technology agreement, much like the End User License Agreements (EULAs) that come with software, spelling out the terms the user agrees to in regards to future use and copy. Farmers purchasing these new seeds were not allowed to save them from their next crop to use the following season, which was common practice among some soybean and canola growers. Growers had to choose between the greater expense of the new and more efficient seeds or the parsimony of saving and reusing seed.

According to court records, Schmeiser first discovered Roundup-resistant canola in his crops in 1997. He’d been using Monsanto’s Roundup herbicide to clear weeds around power poles and in ditches next to a public road running along one of his fields. Schmeiser noticed that some of the canola he sprayed survived. He then performed a test by applying Roundup to an additional three to four acres of the same field. He found that 60% of the canola plants survived. At harvest time, Schmeiser instructed a farmhand to harvest the test field. That seed was stored separately from the rest of the harvest and used the next year to seed approximately 1,000 acres of canola. Whether Schmeiser came into possession of Roundup Ready canola due to accidental contamination in 1997 is unclear. The court case concerned the seed that he saved and used to benefit from the herbicide-tolerance trait.

According to the record presented in the Canadian Supreme Court finding on the case, a Monsanto investigator took samples of canola from the public road allowances bordering on two of Mr. Schmeiser’s fields in 1997, all of which were confirmed to contain Roundup Ready Canola. In March 1998, Monsanto visited Mr. Schmeiser and put him on notice of its belief that he had grown Roundup Ready Canola without a license.

Mr. Schmeiser nevertheless took the harvest he had saved in a pickup truck to a seed treatment plant and had it treated for use as seed. Once treated, it could be put to no other use. Mr. Schmeiser planted the treated seed in nine fields, covering approximately 1,000 acres in all. Numerous samples were taken, some under court order and some not, from the canola plants grown from this seed. Moreover, the seed treatment plant, unbeknownst to Mr. Schmeiser, kept some of the seed he had brought there for treatment in the spring of 1998 and turned it over to Monsanto. A series of independent tests by different experts confirmed that the canola Mr. Schmeiser planted in 1998 was 95% to 98% Roundup resistant.

The question then was not, as is frequently characterized in the public imagination, whether Monsanto sued a hapless farmer after his crops were accidentally contaminated, but whether Monsanto retained patent protections over the genes in the seeds Schmeiser saved and intentionally reused. That he tried to obscure the fact that he intentionally saved 1,000 acres’ worth of Roundup Ready canola to plant in 1998 complicates the issue for the anti-biotech groups that backed his case.

Further complicating things, Schmeiser apparently didn’t spray his 1,000 acres of herbicide-tolerant canola with Roundup, and he sold the seed for feed and received no price premium on the sale. But he still benefited from the patented gene because of the risk management aspect of herbicide-tolerant (or insect-resistant) crops. That is, at the beginning of the season, the farmer doesn’t necessarily know the weed pressures they will face, so some of the value comes from the option to spray Roundup if weeds arise. The court further found that, although not directly at issue in the case, cultivating Roundup Ready Canola also presented future revenue opportunities to “brown-bag” the product to other farmers unwilling to pay the licensing fee, thus depriving Monsanto of the full enjoyment of its monopoly.

If Schmeiser’s goal was to weasel out of a judgment, it made sense to cloud the issue. But if his goal was to test the extent of Monsanto’s patent monopoly on the trait once it unintentionally came into a farmer’s possession, Schmeiser should have been upfront about what he did, the case would have been stronger. He gained control of the seeds by chance and claimed he had the right to do with them what he wanted as a result. The court disagreed.

Despite the popular thumbnail portrayal of Monsanto suing farmers for accidental contamination, the case of Monsanto v Schmeiser hinged on whether Percy Schmeiser could intentionally breed Roundup Ready canola for his own commercial use having gained possession of it in a non-commercial avenue. What’s ironic is that Schmeiser became a folk hero to anti-biotech critics of ‘chemical’ farming because he wanted to use biotech seeds that are yoked to ‘chemical’ farming. He just didn’t want to pay for it, as the law demanded.

You can argue that patent and seed-development laws are unjust or counterproductive. I think that case is reasonable though ultimately flawed. But whatever side of that argument you land on, it’s wrong to say that Monsanto went around suing farmers for accidental pollination just as Roundup Ready technology was gaining traction and the legal framework that facilitated the technology was developing.

So, perhaps the lawsuit against Schmeiser was defensible. But what about the other cases of Goliath Monsanto suing hapless David farmers? We’ll explore those cases in part two of this series.

Marc Brazeau is the GLP’s senior contributing writer focusing on agricultural biotechnology. Follow him on Twitter @eatcookwrite