The New York Times’ Nicholas Kristof has shown an admirable commitment over the years towards highlighting under-reported stories. He fights for the underdog, often in the developing world. That’s all the more reason why his recent column, “What are sperm telling us?”, was so disappointing.

The article, one of the most read stories on the paper’s website for more than a week, focuses on a four-year old study that has been seized on to promote a theory about why sperm counts are falling and egg quality shows signs of decline. It’s an important issue. Kristof sub-heads his column with what he believes is the smoking gun: “Endocrine-disrupting chemicals may be the problem.”

As an epidemiologist who has spent my entire career studying chemicals and their effects on human health, that’s a problematic theory, at best. Kristof’s commentary, and in fact the research that he selectively cities, tell only part of a complex story about the impact of exposure to environmental chemicals. Rather than conveying the grays of science, he ends up promoting the most sensational, almost black and white, and least probable explanations of a serious environmental and health issue.

How do Kristof’s experts portray the science?

At issue is a 2017 meta-analysis of studies examining sperm counts in different countries. The study, spearheaded by Shanna Swan, an environmental scientist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City, reported that from 1973 to 2011 the sperm count of men in Western countries had fallen by 59 percent. In contrast, no significant decline was seen in other parts of the world (however fewer studies were available from these regions). The results of this high-quality analysis confirmed earlier, but less reliable, reports of falling sperm counts. In addition, the results showed that the trend is continuing.

Kristof wrote a remarkably similar column about the meta-analysis, “Are Your Sperm in Trouble,” when it first came out. The selective evidence he chose to feature painted a distorted picture of the science, as I pointed out in a column in Forbes:

“The question of sperm quality has been a focus of scientific discussion for over twenty-five years, and a wealth of serious, well-conducted studies provide no support for the claim that male reproductive function is under threat. What is in trouble is our ability to look beyond isolated results from studies that are held up to inspire fear but that are, at best, difficult to interpret and, at worst, meaningless.”

– Geoffrey Kabat, 2017 Forbes column

Kristof’s recent column reprises but doesn’t advance his thesis by interviewing four scientists who believe that evidence points to endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs), which mimic the body’s hormones, disrupting normal developmental processes, as the culprit.

One of those scientists is Professor Swan, who was the senior author on the 2017 meta-analysis. As it not-so-coincidentally happens, she has just published a book with the clinically detached title: Count Down: How our modern world is threatening sperm counts, altering male and female reproductive development, and imperiling the future of the human race.”

Presumably echoing Swan, Kristof tells us that, “These endocrine disruptors are everywhere: plastics, shampoos, cosmetics, cushions, canned foods and A.T.M receipts. They often aren’t on the labels and can be difficult to avoid.” Swan’s ‘practical’ suggestions for reducing exposure to EDCs are eye-opening:

“Store food in glass containers, not plastic. Above all, don’t microwave foods in plastic or with plastic wrap on top. Avoid pesticides. Buy organic produce if possible. Avoid tobacco or marijuana. Use a cotton or linen shower curtain, not one made of vinyl. Don’t use air fresheners. Prevent dust buildup. Vet consumer products you use with an online guide like that of the Environmental Working Group.”

This list is noteworthy for combining the impractical: don’t use plastic containers; with the impossible: buy organic and avoid pesticides (which are used by all farmers, conventional and organic). Some of the advice is simply ridiculous: don’t use a plastic shower curtain (exactly how many endocrine-disrupting molecules are off-gassing from your vinyl shower curtain?).

It’s also troubling that Kristof and Swan tout the Environmental Working Group, an environmental advocacy group funded in part by the organic industry [read the GLP Profile of the Environmental Working Group]. EWG is notorious for not following standard protocols for measurement of pesticide residues in produce. It is also notorious for putting out an annual “Dirty Dozen” list of ‘pesticide soaked’ fruits and vegetables that is widely decried as scientifically illiterate (here, here, here), including by the USDA, during the Obama Administration.

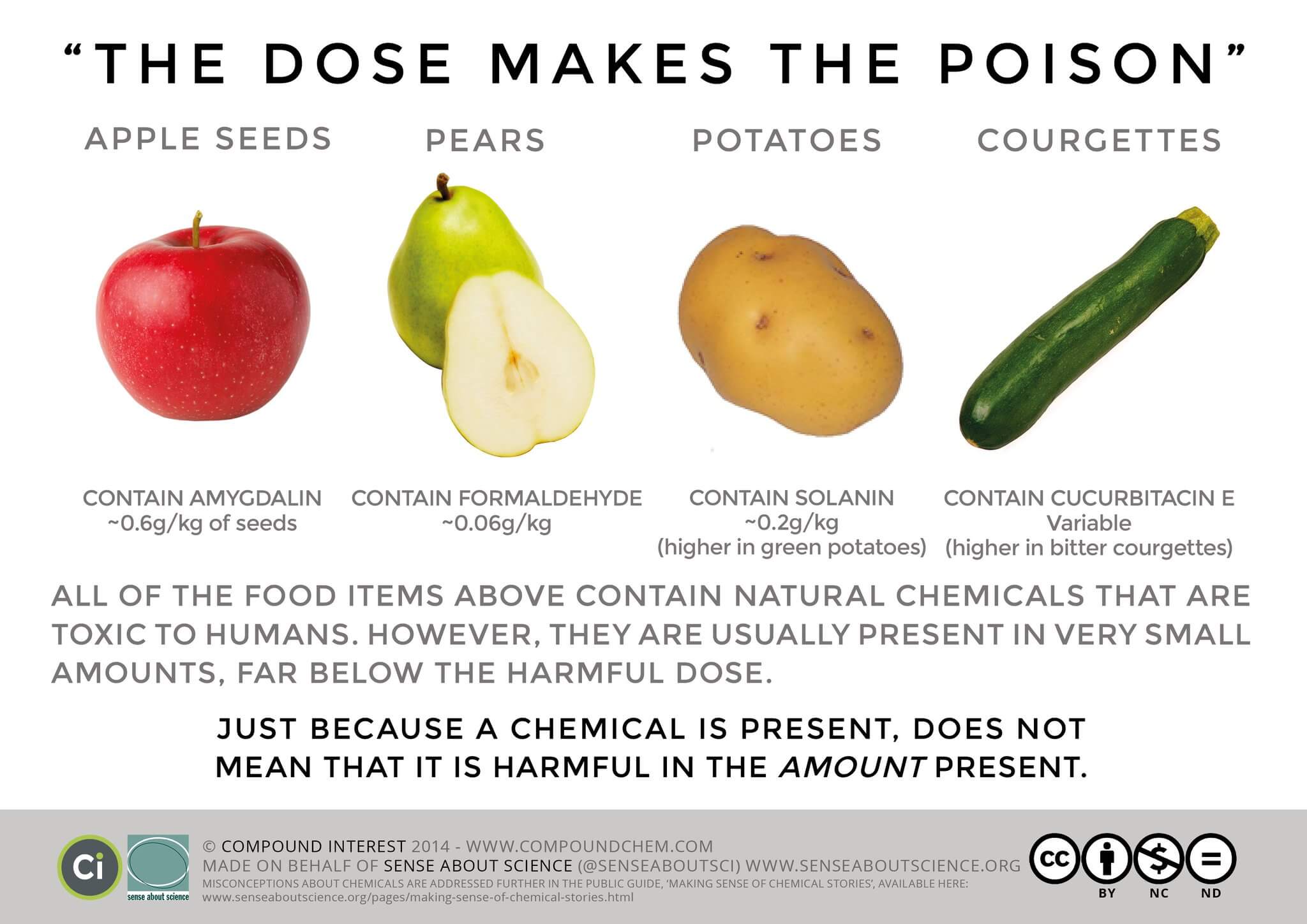

The dose poisons the reporting

In addition to Swan, Kristof brings in three other scientists, all strong proponents of the belief that EDCs are responsible for a number of apparent trends in reproductive health, including the declining age of onset of puberty in girls, an increase in male reproductive anomalies, an increase in testicular cancer, as well as falling sperm counts.

It is a telltale sign that, at no point in his article or in any quote from the experts he interviewed, is the theory of EDCs ever explained; it’s presented as if it is established science, which it is not. Nor do the scientists address a fundamental tenet of toxicology: the dose makes the poison. In fact, the notion of the dose of exposure to EDCs is not even mentioned.

This oversight is an almost universal feature of reporting of low-level environmental hazards in the media. Scientists know that it is the dose, in conjunction with the potency of a substance, that determines its effects. But there is a complicity or sloppy ignorance between scientists, eager to get exposure for their work, and journalists in ignoring this crucial fact.

In reality, biomonitoring of populations indicates that, while exposure to certain chemicals may be detectable in children and adults using modern, ultra-sensitive analytic methods that find traces in the parts per million, billion, or even trillion (akin to one grain of sand in an Olympic sized swimming pool), we are essentially talking about micro-trace amounts that have no health impact.

The single-minded belief of ‘true believers’ among scientists and the media that they know what is causing highly complex and varied phenomena, while reinforcing the public’s fear of trace exposures to “chemicals,” effectively obscures a much more complex, and not nearly as lurid, picture.

What activist scientists and journalists are not reporting

Missing from Kristof’s column is any understanding that the scientists he quotes are not representative of views in the scientific community. A very different picture emerges when one listens to some of the foremost authorities in the field of reproductive health.

Richard Sharpe is in the Medical Research Council at Edinburgh University and one of the world’s foremost endocrinologists. He is the research scientist who originated the notion and study of ‘endocrine disrupting chemicals’ in the 1990s.

Over the years, after participating in and reviewing hundreds of studies on EDCs, he is convinced the concept is wrongheaded—an ideological belief and not science based. Speaking to The Guardian, he stressed the lamentable degree of our ignorance concerning the array of factors influencing healthy male reproductive development due to a lack of research investment.

“We need a critical mass of scientists trying to find out what is happening and why it is happening. Unfortunately, we still do not have that. Not enough research is being done. Yet I believe the problem is getting worse.”

On what might be causing the decline in sperm counts, Sharpe added: “Given that we still do not know what lifestyle, dietary or chemical exposures might have caused this decrease, research efforts to identify (them) need to be redoubled and to be non-presumptive as to cause.”

After interviewing Sharpe in 2017, the science journalist Philip Ball wrote that, “Sharpe suspects that diet, lifestyle, medications and environmental chemicals all play roles, possibly in that order.”

Sharpe’s analysis, unlike Swan’s is entirely mainstream. As Professor Allan Pacey of Sheffield University commented, “Almost every aspect of modern life, from mobile phones to smoking and oral contraceptives [contaminating drinking water], has been blamed for declining sperm counts, but no convincing evidence has emerged to link any of them to the problem.”

Kristof’s column exemplifies a deep-seated split in the area of environmental epidemiology and toxicology. On the one hand are scientists who take a broad view of normal reproductive development in order to understand where the process might go awry, leading to various pathologies. As this is science in shades of gray rather than black-or-white, this perspective is often not widely reported. After reviewing hundreds of studies over more than two decades investigating possible effects of EDCs, the Environmental Protection Agency has concluded, “limited evidence exists for the potential of chemicals to cause these effects in humans at environmental exposure levels.”

On the other hand are researchers, primarily research toxicologists, who view most pathologic conditions through the lens of exposure to EDCs, ignoring or downplaying the possibility that many other maternal exposures during pregnancy with much greater effects (obesity, smoking, sedentary behavior, intake of a calorie-dense diet, use of medications, etc.) are playing a role. This is a scientifically hazy and unprovable claim despite decades of research, but it captures the imagination of journalists and ultimately of many politicians and regulators.

Unfortunately, by leveraging the media (and often partnering with tort lawyers), these ‘advocacy scientists’ generate massive reams of dubious-quality research, sucking up the bulk of public funding that should be devoted to the more difficult work of elucidating the complex pathways of healthy reproductive development.

Geoffrey Kabat is a cancer epidemiologist and the author of Getting Risk Right: Understanding the Science of Elusive Health Risks. Find Geoffrey on Twitter @GeoKabat