- Argument from Futility

- Argument from Perversity

- Argument from Jeopardy

Read part 1 here: Viewpoint — Anti-GMO activists conjure up new scare messages as their influence wanes

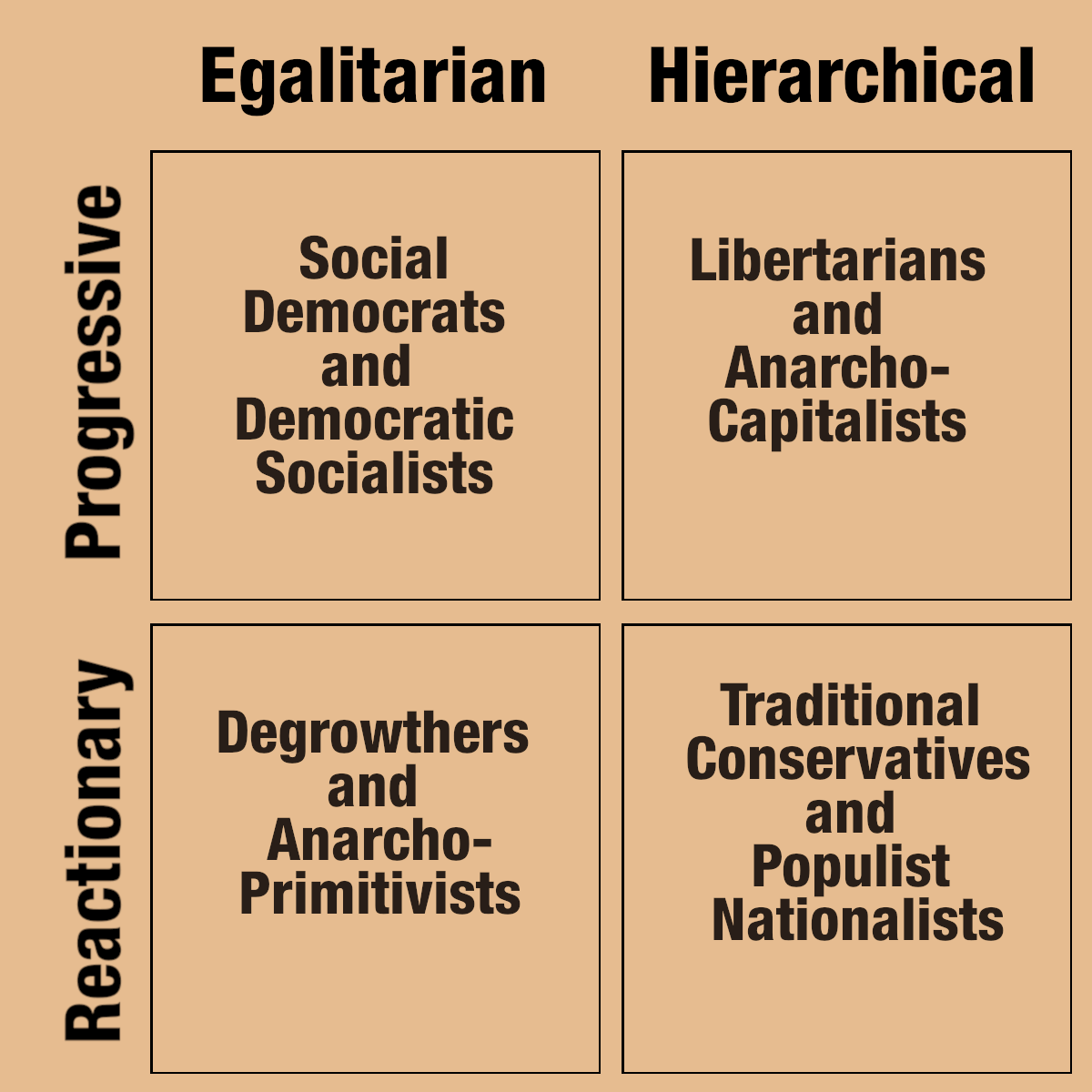

Before digging into how the main thesis of The Rhetoric of Reaction has played out in the anti-GMO movement, it’s worth clarifying why the anti-GMO movement, which considers itself motivated by progressive principles, is in fact reactionary. Much of the leadership and activist base are broadly associated with the left, advocate for broadly egalitarian outcomes and identify themselves as progressive. However, their attitudes towards technology in agriculture (and often other technological innovations, such as nuclear energy) are quite reactionary.

What is Progressivism?

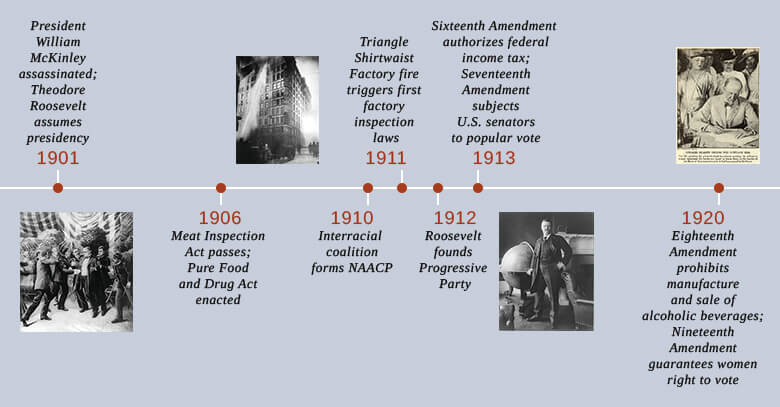

I think it’s helpful to separate two impulses into two different axes. Let’s start with the original political meaning of progressive from the Progressive Era, which in the United States encompassed the post-Civil War period of intense social and political reform, embracing a belief that social tinkering could make progress toward a better society. The movement arose out of the optimism of the Enlightenment in the 18th century, and originally focused on social progress of the broadest sense.

From the early 1890s into the twentieth century, what became known as the Progressive Era took hold as a political movement, embracing the popular belief that society is inexorably moving forward. Its adherents were first and foremost committed to modernization more than economic redistribution. They focused on progress — grounding reforms on a scientific basis, and with good government reform based on the professionalization of the bureaucracy.

Progressivism is generally associated with egalitarianism and reactionaries generally favor hierarchy, But the original Progressives reflected a way of thinking that incorporated elements of both left and right. The counterpoint of the progressives were traditionalist conservatives, those who were skeptical and even hostile to significant social, political, scientific and economic change. At the far end of the conservative spectrum were reactionaries and populists. It’s helpful to differentiate between progressive vs. reactionary and hierarchical vs. egalitarian as a way of illustrating how extremist elements of the left and right can draw on key personality traits.

Not all the progressivism was egalitarian.

Today’s progressives would likely be surprised that Frederick Winslow Taylor’s The Principles of Scientific Management, published in 1910, smack dab in the middle of the modern Progressive Era, very much embodied the spirit of the times. Hardly a supporter of loosening the chains on workers often laboring 12 hours a day, Taylor infamously wrote:

It is only through enforced standardization of methods, enforced adoption of the best implements and working conditions, and enforced cooperation that this faster work can be assured. And the duty of enforcing the adoption of standards and enforcing this cooperation rests with the management alone

Celebrated at the time as a leading Progressive-era spokesman, Taylor attempted to rationalize the organization of the oppressive factory system of that era; he optimized for efficiency, much to the chagrin of many workers and their advocates.

Eugenics

The streams of political movements often create powerful cross-cutting currents. And they often age poorly.

Progressivism had an increasingly dark side in the 1920s and 30s. The emerging field of eugenics was embraced by many of the leading progressives of this era who saw the movement as a ‘scientific way’ of improving the ‘good genes’ in society. For some, it was a sincere, if naive, hope that managing genetics could reduce social problems and increase human thriving. As Princeton University scholar Thomas C. Leonard pointed out in his 2016 book “Illiberal Reformers: Race, Eugenics & American Economics in the Progressive Era,” progressives believed that scientific experts should determine the “human hierarchy” through appropriate social policies, which included eugenics.

Margaret Sanger, the founder of Planned Parenthood, was motivated in part by the progressive eugenic desire to remake humanity for the better.  Some activists today argue for the removal of memorials in her name because she advocated for “the gradual suppression, elimination and eventual extinction, of defective stocks — those human weeds which threaten the blooming of the finest flowers of American civilization.” While Sanger’s motivation’s are complex, in some quarters, especially on the far right, eugenics was a fig leaf for deeply racist attitudes that culminated in fascism, National Socialism of the Nazis, and the Ku Klux Klan.

Some activists today argue for the removal of memorials in her name because she advocated for “the gradual suppression, elimination and eventual extinction, of defective stocks — those human weeds which threaten the blooming of the finest flowers of American civilization.” While Sanger’s motivation’s are complex, in some quarters, especially on the far right, eugenics was a fig leaf for deeply racist attitudes that culminated in fascism, National Socialism of the Nazis, and the Ku Klux Klan.

A resistance to change is a current that runs through both the historical Progressive movement and classic conservatism. William F. Buckley, the founding editor of the conservative journal National Review gave this definition of a conservative in the 1950s: “A conservative is someone who stands athwart history, yelling Stop, at a time when no one is inclined to do so, or to have much patience with those who so urge it.” That provides a framework for understanding the essentially conservative actions of self-proclaimed progressives who stridently campaign against biotechnology.

So, while there are various leading lights of the anti-GMO movement who want to center environmentalism as a political cause, who advocate for the interests of farmworkers and smallholder farmers, we can also recognize that their posture towards genetically engineered crops in particular and technologically progressive farming, in general, draws on their conservative bent—which at its most extreme can become strident and reactionary.

We can recognize these tendencies in anti-GMO activists. Indian anti-modernity campaigner Vandana Shiva (responsible for the organic-only agricultural catastrophe in Sri Lanka) or Andrew Kimbrell of the Center for Food Safety (a group that files lawsuits to block new biotech crops) or labeling activist Stacy Malkin of U.S. Right to Know are what could be called ‘reactionary egalitarians’— closer to classic conservatives than modern-day liberals.

While anti-GMO sentiment may be led by people associated with the political left, make no mistake, the anti-GMO/anti-modern agriculture movement is an anti-progress, reactionary movement. This becomes all the clearer when we see that they routinely employ the rhetorical strategies of reactionaries, as identified by Hirschman.

Futility Thesis

What’s known as the Futility Thesis holds that attempts at social transformation will be fruitless. They will simply fail to make a dent. This was particularly vivid in the attempt to disparage the Golden Rice project in the Philippines.

Golden Rice was developed as an easy (and affordable) way to help treat vitamin A deficiencies, a leading cause of blindness in developing countries. It is genetically engineered to produce beta-carotene, the chemical predecessor of vitamin A. An estimated 250,000–500,000 children who are vitamin A-deficient become blind every year, and half of them die within 12 months of losing their sight. An early version of the rice did not deliver sufficient amounts of beta-carotene to deliver the intended health benefits. This fact was seized on by anti-GMO activists and endlessly repeated, years and years after newer generations of Golden Rice were delivering ample amounts of beta-carotene.

Likewise, activists also seized on the fact that beta-carotene requires dietary fat to convert into vitamin A. The low-income populations that Golden Rice is intended for frequently have a very low-fat diet due to the cost of fats. This was taken as evidence that Golden Rice just wouldn’t work. That position ignored the fact that converting Golden Rice into vitamin A requires only very small amounts of dietary fat. It did not pose a real-world challenge at all. Many of those same people braying that the intended beneficiaries didn’t have access to fat in their diet couldn’t see why the poor can’t be provided with more expensive, perishable fruits and vegetables instead of a cheap, non-perishable staple crop that delivered the main nutrient missing from their diets. The opposition took violent turns, with Greenpeace-led activists destroying trial plots, delaying pivotal research for years.

Despite bad faith campaigns misrepresenting both the need and the science, Golden Rice was approved for commercialization in the Philippines, and the planting of the first crops has begun. The hollow and dishonest anti-GMO arguments have been laid bare. Next, we will see if the activist assertion that people won’t accept Golden Rice for cultural reasons faces the same fate.

Perversity Thesis

According to the Perversity Thesis, any purposeful action to improve some feature of the political, social, or economic order will only serve to make the situation worse. We could see this strategy a few years back when insects in the U.S. corn belt were developing resistance to insect-repelling Bt corn (in which the plant is genetically engineered to produce a natural Bacillus thuringiensis toxin that kills corn borers; Bt in spray form is widely used by organic farmers).

This certainly was a challenge for farmers in their pest management strategies. It did involve bringing back pesticides that they’d been able to forgo when Bt crops were first introduced but on a limited scale. So, insecticide use did rise for a few years, although those trends have since sharply reversed as farmers introduced more comprehensive IPM—integrated pest management. In reality, since the introduction of Bt crops in the mid-1990s, farmers had been able to reduce the relevant insecticides by from 30% to as much as 90%.

To read the disingenuous anti-GMO coverage of the issue, the entire strategy of insect-resistant crops was backfiring and the use of insecticides was coming back with a vengeance. When insecticide use briefly increased by 20% it seemed more significant than it was. If you reduce something from 100 down to 10, if it increases by 20%, this leaves you at 12. Hardly an apocalyptic result. Over time, farmers who had become lax with their integrated pest management (IPM) became more disciplined and improved varieties and Bt traits were developed that were more resilient. Today, no one doubts the resounding success of Bt crops when intelligently managed. While the naysayers have gone silent, their deceptive narrative remains on the internet forever.

Similar arguments were made when a golden age of glyphosate (aka Roundup) came to an end with weeds developing stronger resistance to the weed-killer. Glyphosate is a mild herbicide, confirmed in more than six thousand studies evaluated by 19 independent global regulatory and safety agencies to be both effective and safe to humans and the environment. Although glyphosate was remarkably effective, weeds gradually began developing resistance in cases where the weedkiller was overused or other chemicals were not rotated in. Farmers needed to start getting serious about IPM for weed management in a way they hadn’t in a generation. Which they mostly have.

But to hear anti-GMOers tell it, putting some older, but still widely used technologies like 2,4D and Dicamba back into the mix was an unmitigated disaster. While the rollout of Dicamba-resistant soybeans was a disaster for the first few years, we are nowhere near having gone backward compared to the weed control regime that existed prior to the introduction of Roundup Ready crops. In the scheme of things, the resistance problems initially caused by glyphosate are small, containable and in most cases have receded.

The Jeopardy Thesis and the Terminator Seeds Myth

Finally, the Jeopardy Thesis argues that the cost of the proposed reform is too high and endangers some previous accomplishment. The greatest anti-GMO insistence on jeopardy was a whale of a tale, too delicious to pass up retelling here.

In the early days of biotech crop breeding, skeptics of the new technologies worried about cross-pollination to traditional crops. One proposed solution to this was Genetic Use Restriction Technology (GURT). The mechanism was developed in labs in the 1990s. The technology had a few moving parts but the basic idea was that GMO seeds would be infertile in the second generation. Cross-pollination could not spread genetically engineered genes to neighboring fields. GURT got tagged with the ominous nickname Terminator Seeds. The technology faced several criticisms, among them the fear that the major seed companies would gain market power by selling seeds that could not reproduce. That mattered for soybean farmers in Africa, if not for corn farmers in Iowa. Subsequently, the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity adopted a de facto moratorium in 2000, and the technology was withdrawn and has never been deployed.

That didn’t stop anti-GMO cranks from fear-mongering about so-called ‘Terminator Seeds’. To this day, you will find anti-GMO keyboard warriors who cite Terminator seeds among their objections to GMOs. Much of this traces back to the anti-modernity, food sovereignty activist Vandana Shiva, one of the most reactionary anti-GMO cranks. Here is Shiva on the issue of so-called Terminator Seeds:

2000: The gradual spread of sterility in seeding plants would result in a global catastrophe that would eventually wipe out higher life forms, including humans, from the planet.

2012: The minute seeds stop being the seeds of renewal and start being the seeds of death-like the terminator technology, creating sterile seeds, patented technology that makes it illegal for farmers to save and exchange seed, we get scarcity, that is why a quarter million Indian farmers have committed suicide.

The myth of the alleged threat from Terminator Seeds became a staple of the ant-GMO movement. There is so much wrong here, it’s hard to know where to start.

There is so much wrong here, it’s hard to know where to start.

- When the Green Revolution brought hybrid rice and wheat to Mexico, India, Pakistan, and the Philippines in the 1960s and 70s, the result was not scarcity. The result was abundance and the avoidance of famine. This was in spite of the fact that farmers do not save hybrid seeds because hybrids don’t breed true in the next generation.

- India was suffering from a wave of farm suicides at the time Shiva was making those remarks. However, the reason was the lack of credit and risk management for Indian farmers. The only biotech crop in India was cotton. Cotton farmers had lower rates of suicide than their peers in other crops. In fact, Bt cotton in India was approved over elite objections due to grassroots pressure from farmers. They were smuggling Bt cotton seed into the country and the government had no way of regulating the black market seeds.

Sterility, as a genetic trait, can’t spread. Not gradually, not rapidly, not in a house, not with a mouse, not in a box, not with a fox. It cannot happen here. It cannot happen there. It cannot happen anywhere. This is one of the most biologically preposterous statements in the history of preposterous statements. And yet, you’d be surprised how many people saw it as alarming, farsighted, and wise. Even if we grant the most charitable interpretation — that she wasn’t referring to widespread sterility through cross-pollination but rather by the commercialization of GURTs. The pathway to “a global catastrophe that would eventually wipe out higher life forms, including humans, from the planet” is hard to grasp given the vast amounts of food already produced by farmers who don’t save seeds because they use hybrids.

Facts will not deter the likes of Vandana Shiva from continuing to spread misinformation, about so-called Terminator Seeds and genetically engineered crops in general. In a review of Shiva’s book Staying Alive: Women, Ecology and Development, essayist Marco Rosaire Rossi highlights the depths of Shiva’s antipathy to science and rationalism.

At the heart of Vandana Shiva’s view of the world is the idea that the major problems facing women, indigenous peoples, and the environment have their roots in Europe’s move towards rationalism and scientific thinking. She refers to this movement as “reductionism”—but she so often associates “reductionism” with patriarchy and colonialism that it almost seems as if she has redefined “reductionism” to be synonymous with these terms. In any case, for Shiva the rise of “reductionism” began with the European Scientific Revolution, which—according to her– “turned woman and nature into passive objects, to be used and exploited for the controlled and uncontrollable desires of men.” The idea that women and nature were “turned” into passive objects implies that before this time everything was fine, or at least much better.

Your mental model makes predictions whether you admit it or not

We all have mental models of how the world works, some of which are clear and we are conscious of. Some are implicit and subconscious. Nevertheless, implicit in all mental models of how the world works are predictions about how the world WILL work with the passage of time. The arguments from perversity, futility, and jeopardy embody conservative assumptions about society and human nature. Hirschman’s purpose was not to say that they are wrong. One of the reasons the arguments are effective is that sometimes that’s how the world works. Sometimes reforms are poorly designed and don’t make a dent in the problem. Sometimes reformers don’t pay attention to perverse incentives and make the problem worse. And sometimes making things worse could pose a serious problem.

Seeing the patterns and structure of these arguments lets us see the political aims and biases behind them. This helps us more clearly see their hidden assumptions. It helps us identify the predictions built into the criticisms of GMOs made by anti-GMO activists. We can then test them as their expiration dates come due.

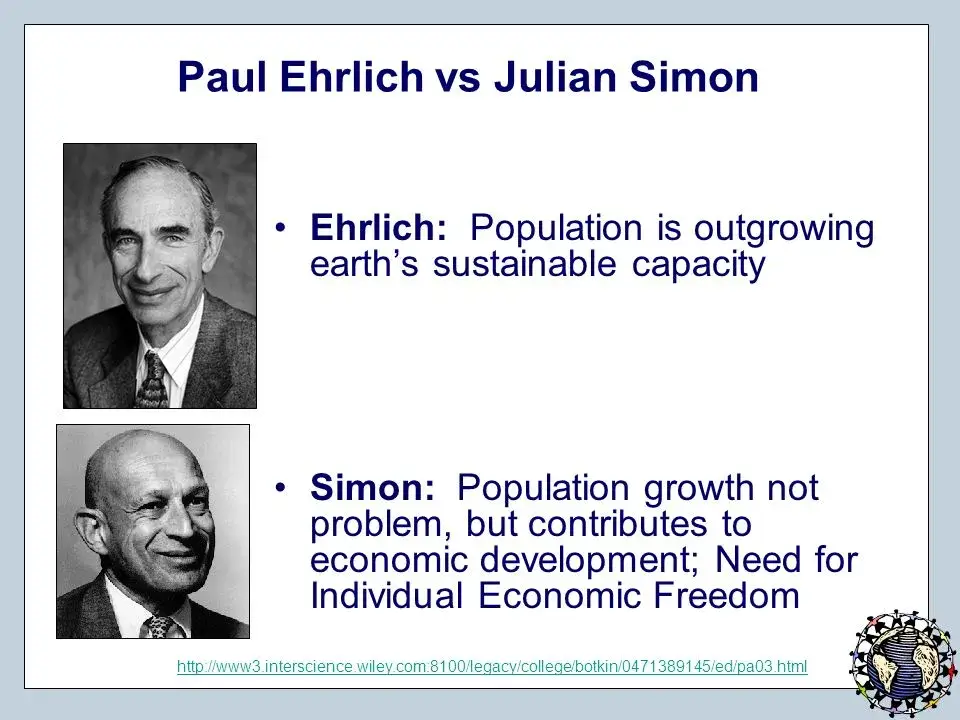

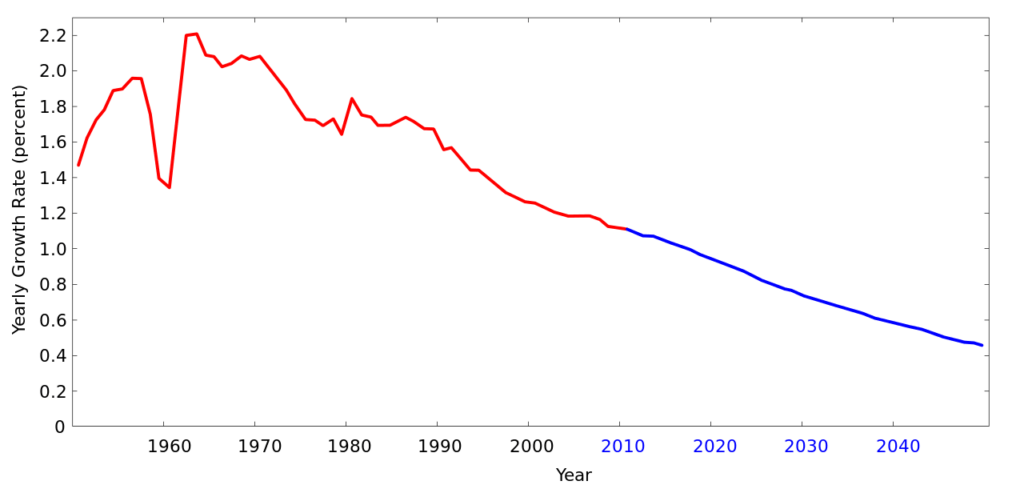

People rarely admit it when they turn out to be wrong. But others are less likely to take them seriously when they engage in serial wrongness. Even then, we are all hard-wired to believe what we want to believe and whatever is useful for ‘our tribe’ to believe. Populist reactionary Stanford University biologist Paul R. Ehrlich stands as an enduring, an embarrassing, symbol of this arrogance. In his 1968 book, The Population Bomb, predicted that fertility rates, particularly in the developing world, were destined to spiral upward for decades to come, sparking famine and instability.

In a bit of science fiction he contributed to Nightmare Age, a collection of doomsday sci-fi from 1969, Ehrlich imagined looking back on the wreckage of The Green Revolution from decades in the future (2022 perhaps).

It became apparent in the early 70s that the “Green Revolution” was more talk than substance. The distribution of high-yield “miracle” grain seeds had caused temporary local spurts in agricultural production. Simultaneously, excellent weather had produced record harvests. The combination permitted bureaucrats, especially in the US Department of Agriculture and the Agency for International Development, to reverse their previous pessimism and indulge in an outburst of optimistic propaganda about staving off famine. They raved about the approaching transformation of agriculture in underdeveloped countries (UDCs). The reason for the propaganda reversal was never made clear. Most historians agree that a combination of utter ignorance of ecology, a desire to justify past errors, and pressure from agro-industry … was behind the campaign. Whatever the motivation, the results were clear. Many concerned people, lacking the expertise to see through the Green Revolution drivel, relaxed. The population-food crisis was “solved.”

But reality was not long in showing itself. Local famine persisted in northern India even after good weather brought an end to the ghastly Bihar famine of the mid-‘60s. East Pakistan was next, followed by a resurgence of general famine in northern India. Other foci of famine rapidly developed in Indonesia, the Philippines, Malawi, the Congo, Egypt, Colombia, Ecuador, Honduras, the Dominican Republic and Mexico.

Everywhere the realities destroyed the illusion of the Green Revolution. Yields dropped as progressive farmers who had first accepted the new seeds found that their higher yields brought lower prices—effective demand (hunger plus cash) was not sufficient in poor countries to keep prices up. Less progressive farmers, observing this, refused to make the extra effort required to cultivate the “miracle” grains … Finally, the inevitable happened, and pests began to reduce yields in even the most carefully cultivated fields … As chaos spread until even the most obtuse agriculturists and economists realized that the Green Revolution had turned brown, the Russians step in…

Ehrlich then imagines that the Russians, attempting to profit from the failure of the Green Revolution, flooding global markets with a hypothetical pesticide — Thanodrin. Thanodrin ends up poisoning the oceans, leading to world war. Futility, perversity, and finally, jeopardy. You can tick them on your fingers in the space of two paragraphs. Instead of averting a crisis, Ehrlich fully expected The Green Revolution to destroy the planet through famine, ecological collapse, and finally war.

Needless to say, know of this drivel came to pass. Ehrlich was spectacularly wrong. A soaring global population and the mass global famines of the 1970s and 80s that he predicted were averted by growing global affluence spurred in part by the Green Revolution — the one he decried — the one that Vandana Shiva and her stable of today’s ‘reactionary progressives’ mock as a ‘chemical induced environmental disaster’.

It should come as no surprise that Ehrlich’s predictions about the then-ongoing Green Revolution mirrored Hirschman’s Rhetoric of Reaction. Ironically, the population crisis he so arrogantly predicted was already abating when his book went to print. The commentator, Jonathan Last called it “one of the most spectacularly foolish books ever published”.

Paul Ehrlich stumbles again

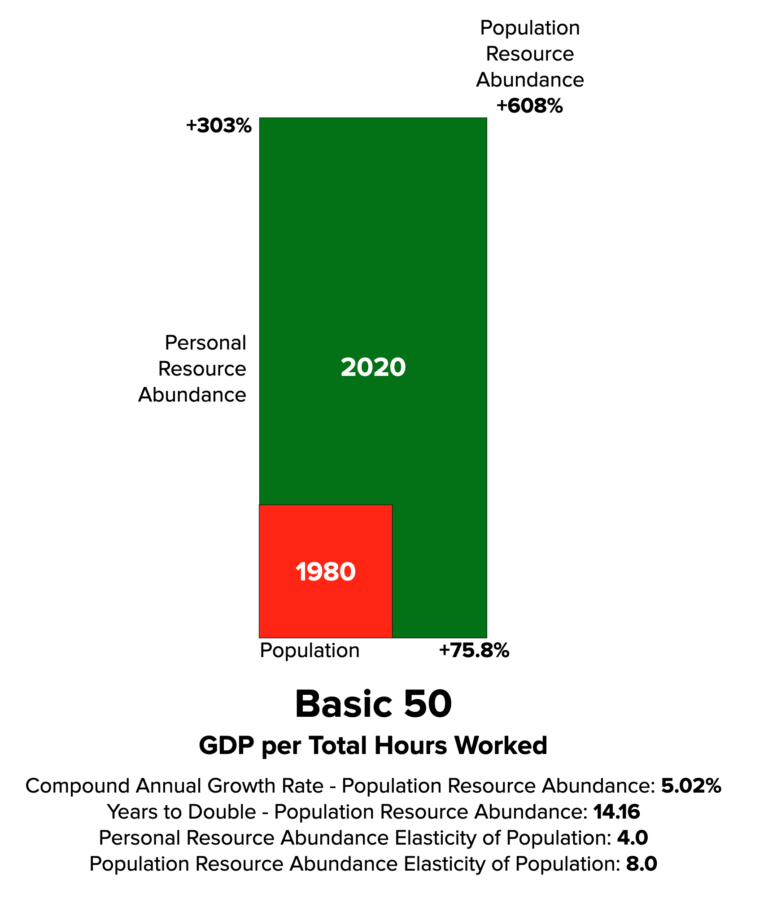

Ehrlich and his progressive supporters were famously and spectacularly wrong again in a highly public wager with the resource economist Julian Simon. In 1980, Simon challenged Ehrlich to put his money where his mouth was. In response to Ehrlich’s published claim that “If I were a gambler, I would take even money that England will not exist in the year 2000,” Simon offered to take that bet, or, more realistically, “to stake US$10,000 … on my belief that the cost of non-government-controlled raw materials (including grain and oil) will not rise in the long run.” Simon challenged Ehrlich to choose any raw material he wanted and a date more than a year away. He would wager on the inflation-adjusted prices decreasing as opposed to increasing. Ehrlich chose copper, chromium, nickel, tin, and tungsten.

The bet was formalized on September 29, 1980, with September 29, 1990, as the payoff date. Ehrlich lost the bet, as all five commodities declined in price from 1980 through 1990. Simon has mapped how spectacularly and consistently wrong Ehrlich’s projections have been. The personal resource abundance multiplier, illustrated below, is calculated by dividing the average time price of the 50 commodities in 1980 by the average time price of the 50 commodities in 2020. The multiplier tells us how much more of a resource a person can get for the same hours of work between two points in time. We find that the same hours of work bought one unit in the basket of 50 commodities in 1980 and 4.03 units in the same basket in 2020. (Simon’s index is bit in-the-weedsy, but it’s clear and persuasive enough if you take the time to read the whole thing.)

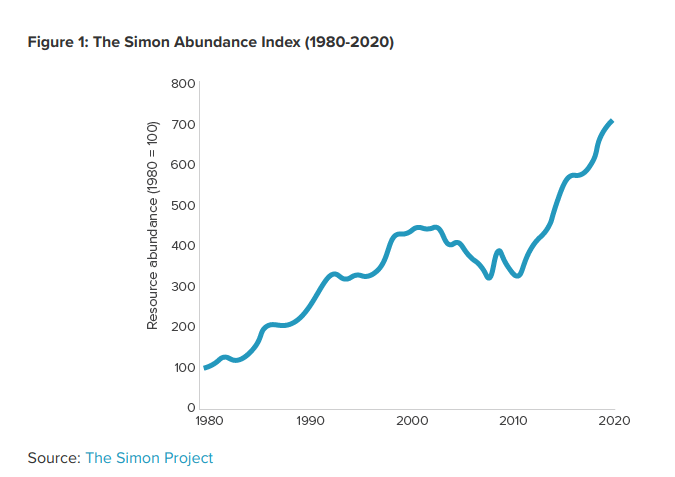

There is now a Simon Abundance Index to track the progress of Simon’s assertion over time, which directly rebuked Ehlrich’s doomsday scenario. In the index, prices are converted into time prices — the number of hours the average worker would have to work to purchase a unit of each commodity — to make comparisons across time meaningful. Over the last 40 years, the average time price of the 50 commodities fell by 75.2 percent. The average inhabitant of the planet’s personal resource abundance rose by 303 percent. The compound annual growth rate in personal resource abundance amounted to 3.55 percent, implying that personal resource abundance doubled every 20 years. Why? Because of dramatic increases in technological innovation — similar to what is happening with biotechnology in agriculture and medicine.

Remarkably and all too predictably, Ehrlich has still not rethought his assumptions despite his spectacularly faulty model. Nor has he been cast out of the academy for being serially wrong; rather he is still feted by the reactionary left, and often cited by anti-biotechnology activists, for his ‘prescient’ warnings about the negative consequences of technological innovation. There are rarely consequences for being wrong unless you are wrong in the wrong ideological way. Likewise, it’s easy to be punished for being correct in the wrong way.

How Progressives twist arguments against technological innovation

In the last section of The Rhetoric of Reaction, Hirschman flips the three reactionary strategies on their heads to find ways in which progressives can make arguments that are simplistic or wishful in their thinking:

- The Synergy Illusion – The idea that all reforms work together and reinforce each other, rather than being competing;

- The Imminent Danger – Urgent action is necessary to avoid imminent danger;

- History Is on Our Side – “The arc of history is long, but it bends towards justice.”

Note that all of them can be associated with sometimes correct, sometimes weak, or overwrought arguments from pro-GMO quarters. While proponents of either side of the GMO divide can broadly identify as right-of-center or left-of-center, on the issue of modern, technological agriculture and genetic modification–from GMOs to gene editing—anti biotechnology activists are the forces of reaction and the pro-biotechnology side in academia and industry are the risk-taking progressives. Either side may get some things right and some things wrong, and I’m admittedly biased towards my side, but the progressive vs. reactionary axis is a clear line in the sand.

We all have our mental models and our mental models all make predictions about how the world will work. None of us like to admit that our views are largely shaped by mental models and assumptions about how the world works. But we can see it when others are wrong. The problem for reactionaries is that their predictions usually come with more clearly defined expiration dates than ‘progressive predictions’.

Marc Brazeau is the GLP’s senior contributing writer focusing on agricultural biotechnology. He also is the editor of Food and Farm Discussion Lab. Follow him on Twitter @eatcookwrite