Beyoncé is facing a lot of criticism for using an ableist slur in her new co-written song Renaissance. She used the word “spaz” twice in a derogatory reference to a neurological disorder in Heated, which dropped in late July.

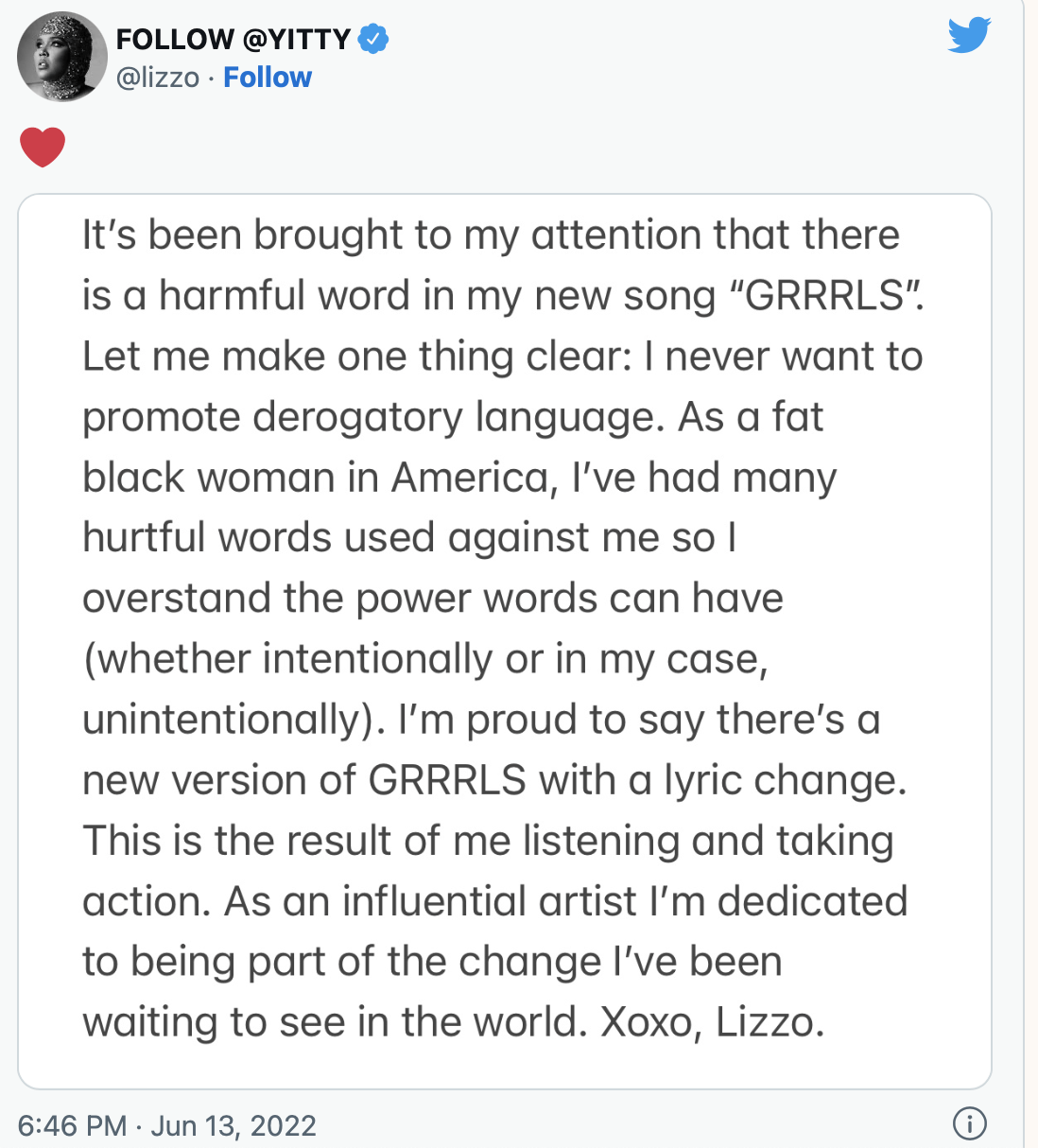

Just a few weeks before, while promoting her new song GRRLS, Lizzo used the same slur. The tweet went viral, prompting a sharp rebuke by Hannah Diviney, who has cerebral palsy. Her tweet also viral, landed on the front page of the BBC, New York Times and the Washington Post.

Lizzo took notice and changed the lyrics. “I never want to promote derogatory language,” she wrote.

I’ve lapsed too in word choices, but I’m not a pop star – I write college life science textbooks. I’m currently revising the 14th edition of my human genetics textbook. I’ve written or co-written four textbooks, totaling 38 editions: intro biology, human anatomy and physiology, and human genetics. Other authors have taken over all but human genetics: I update it every three years.

With each edition, I’ve changed terms in pace with the scientific and medical literature, interviews with experts, and noting the language used at meetings and on webinars.

Trying to use more sensitive language is part of the process and isn’t new. AIDS led me to remove the word “victim” in the context of HIV disease. In 1984 the much-publicized experience of 14-year-old Ryan White who was able to attend school while he had AIDS, led to replacing “hemophiliac” with “person with hemophilia.”

Each textbook go-round updates content and considers reviews from instructors, who echo student feedback. This is not a “woke” exercise. Each go-round requires changes in language to be current with the science and avoid unintentional offense.

Case in point: mental retardation

My book replaced mental retardation with intellectual disability (ID) a few editions ago, when colleagues told me that it would not sell in some countries where it would be deemed offensive. The most recent edition of the DSM-5 (the ‘bible of psychiatry’, if I can say that) changed the term in 2013 to ID, absorbing mental retardation into a “meta-syndromic grouping” of “neurodevelopmental disorders.” The publisher of the DSM, the American Psychiatric Association, still calls the reference the “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders,” so “retardation” is offensive, not “mental.”

For the revision I’m now working on, my publisher hired a company to go through PDFs of all 23 chapters, leaving little yellow flags throughout to alert me to verbiage that might offend a reader, and suggesting substitutions. I call them the PC police, and I don’t necessarily mean that in a judgmental way.

Usually, I take the advice. Some recommendations are obvious, such as replacing “slave” with “enslaved person.” But many criticisms were surprising.

Othering

I had no idea I am an otherer.

In a description of Menkes disease, l point out that it’s also known as “kinky hair disease” because, well, it has been, for decades. I was unaware that hair texture, which is used to assess symptoms in reaching a diagnosis, is a slur. But another yellow flag clarified matters. This citation refers to an end-of-chapter question:

Tribbles are extraterrestrial mammals that long ago invaded a starship on the television program Star Trek. A gene called frizzled causes kinky hair in female tribbles who inherit just one allele. However, two mutant alleles must be inherited for a male tribble to have kinky hair.

The yellow tag reads:

The use of kinky can be considered othering since it is primarily associated with Black hair. In this context, it is literally being used as a trait example for aliens.

For a long time, I had naturally kinky, dark hair. I never thought of myself as an alien.

I did, however, commit extreme othering with:

Some people live in distinct tribes yet go to school and work and dress just like anyone else. But some indigenous tribes are not very different in lifestyle from their hunter-gatherer ancestors.

Cringe. OK, now I get why the publisher hired the PC police. Their critique is spot-on:

These two sentences generalize the Western lifestyle as default and anything else as abnormal, particularly with the phrase ‘just like anyone else.’ It would sound better to use terms that aren’t as othering.

Another sensitive term is “orphan,” as in “orphan disease,” to indicate rarity. The subtext, though, is that the pharmaceutical industry ignores rare diseases because the patient pool is small. The term used to denote a rare disease, which many single-gene conditions are, came from passage of the Orphan Drug Act in 1983. It provided tax credits for clinical research and a 7-year period of exclusivity to encourage drug development for conditions that affect fewer than 200,000 patients in the US. Using “orphan” was a well-meant slight to those who have lost parents.

No more normal

I slashed “abnormal” from the textbook because “normal” is no longer acceptable. People whose cells have extra, absent, or mixed-up chromosomes now have “atypical” rather than “abnormal” chromosomes. But I’m uncomfortable with this ableism extending to the microscopic. I’d still use the ‘abnormal to refer to an ion channel missing a key amino acid, thereby causing cystic fibrosis.

Similarly, birth defects are now congenital disorders. I also changed female and male infertility to infertility in the female/male to separate the condition from the person.

The normal versus abnormal conundrum especially applies to gender.

The PC police strongly advised replacing “homosexual” with “gay,” because homosexual is offensive and dated. That’s true, but “gay” isn’t precise enough — it could mean happy, like in the gay nineties. Google Scholar indicated that many scientific and medical articles still use “homosexual.” Plus, in genetics, the usage is consistent with heterozygote (different variants of a gene) and homozygote (identical variants of a gene). So, I went with “same-sex attraction,” although it sounds stilted and like a disease: “Freddie Mercury had same-sex attraction.”

The PC police missed cis and trans. These are terms from genetics and chemistry and they predate application to sexual attraction among humans by decades.

Race and ancestry

Some criticisms are beyond my control. Citing studies that have mostly non-white participants is sometimes not realistic. I can’t include what doesn’t yet exist. And so, my textbook has several end-of-chapter questions that ask students to interpret data from the UK Biobank studies, which have been based on an initial half million white people. That will change as large-scale genetic research becomes more inclusive.

My textbook’s discussion of race has been praised; I explain why in genetics, identifying people according to ancestry is more meaningful than by subjective sets of traits. But the PC police highlighted my embedded racism. I had no clue how to respond.

Consider part of a question in the evolution chapter based on H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine:

In the distant future on Earth, humanity has diverged. The Morlocks live underground and have dark skin, dark hair, and are aggressive. The above-ground Eloi are blond, fair-skinned, and meek.

Read the yellow tag,

Though this is in reference to a story, this example perpetuates the common literary trope of portraying darker skinned people as subhuman.

The inclusivists must not have seen the film or read the book. The Morlocks were smarter than the Eloi, whom they ate. But I chose to delete the question and was struck by how I could have not noticed the dark=bad light=good imagery, even if it was fiction.

Along the lines of race, I ran into trouble with an image of a beautiful woman selected to illustrate mixed ancestry, describing her skin as “caramel-colored.” The yellow tag points out that “it is best to avoid describing people’s skin as caramel or with food-related examples in general.” Why is caramel offensive? It’s not as if I wrote liver-colored. Or worse.

Along the lines of race, I ran into trouble with an image of a beautiful woman selected to illustrate mixed ancestry, describing her skin as “caramel-colored.” The yellow tag points out that “it is best to avoid describing people’s skin as caramel or with food-related examples in general.” Why is caramel offensive? It’s not as if I wrote liver-colored. Or worse.

And then there’s the consensus on what to call Black people.

The most recent textbook edition, published in 2021, uses “African American,” as did all previous editions, based on instructor feedback. “Black people” obscures the specificity of ancestry that is at the heart of genetics. And the capital B, compared to the lower-case w in white people, per my publisher’s style sheet, reflects sociology, not biology.

In order to study origins, evolution and ancestry, we need to know where people came from, because much of the modern human African genome is ancestral to us all. Disguising that to appease political correctness is not helpful in explaining genetic principles.

Along with African-American, other recently retired terms include aboriginal American, Eskimo and Native American.

“Tribe” is verboten, replaced with Indigenous People, First People, or First Nation. Best is to use precise names, such as Cherokee and not Native American, or the word used in classic Westerns.

Indigenous Peoples especially do not want to be referred to as “vanishing.”

A blight in the history of genetics was the Human Genome Diversity Project of the 1990s. Researchers, most of them white and from privileged nations, sought DNA from Indigenous Peoples, such as Australian Aborigines.

When Australia was colonized in 1788, the Aborigines had already been there for 55,000 years, making them one of the oldest Indigenous Peoples outside Africa.

“We had to tell them we had to take samples before they vanish,” a researcher who was part of the project, Sheila van Holst Pellekaan of the University of New South Wales, told me in 2011.

But a blood sample wasn’t necessary. The Aborigine genome was sequenced from a museum hair sample from a young man from the 1920s, van Holst Pellekaan said. She advised researchers to seek consent from the man’s descendants, which they did.

Geographical origin, then, trumps traits in genetics. But writing about places requires sensitivity too. Chang and Eng weren’t famous Siamese twins, the yellow flag told me. They were famous conjoined twins.

Specificity is important too. Burkitt’s lymphoma isn’t “a cancer common in Africa,” as my textbook reads. The yellow flag points out that “labeling this illness as common to all of Africa instead of specifying a country or region risks portraying Africa as disease-ridden.”

Inclusivity in education

To summarize, according to the inclusivity checkers, some of the wording in my textbook is otherist, ableist or racist. I hope my revision remedies the charges.

I became fascinated with the little yellow flags peppering my pages, and did some digging. I found an eclectic literature on the “ists.”

Fourteen Recommendations to Create a More Inclusive Environment for LGBTQ+ Individuals in Academic Biology , from 2020, didn’t pose a problem for my book. The “Matters of Sex” chapter has always included the table “Sexual Identity.” It distinguishes chromosomal genetic sex, gonadal sex, phenotypic sex, gender identity and sexual orientation. The chapter’s Bioethics box, “Probing a genetic basis of transgender identity,” is adapted from an article I wrote featuring the work of a top researcher .

A report in the Journal of Research in Science Teaching, from investigators at the University of Akron, “Queering High School Biology Textbooks,” from 2004, scared me. They analyzed eight textbooks in light of “queer theory.” The authors conclude that the selected textbooks:

…offer deafening silences, antiseptic factoids, socially sanitized concepts, and politically correct binary-gendered illustrations. In these textbooks, the term ‘homosexuality’ was used only in the context of AIDS where, along with IV drug users, they were identified as an affected group. The pervasive acceptance of heteronormative behavior privileges students that fit the heterosexual norm, and oppresses through omission and silence those who do not.

I hope my book wasn’t among the eight. I could only see the abstract.

Complementing the academic views is a New York Times op-ed by Emma Camp, a former student at the University of Virginia, “I Came to College Eager to Debate. I Found Self-Censorship Instead.”

“During a feminist theory class in my sophomore year, I said that non-Indian women can criticize suttee, a historical practice of ritual suicide by Indian widows,” she wrote. One by one, the class turned on her, and she learned not to speak up.

Emma Camp used to write an opinion column for UVA’s Cavalier Daily,

I was shaken, but also determined to not silence myself. Still, the disdain of my fellow students stuck with me. I was a welcomed member of the group — and then I wasn’t. … Being criticized — even strongly — during a difficult discussion does not trouble me. We need more classrooms full of energetic debate, not fewer. But when criticism transforms into a public shaming, it stifles learning.

Repealing Roe v Wade

I’d planned for months to write this post, waiting until I’d plowed through all the yellow flags pointing out my insensitivity. With two chapters left to revise, however, the Supreme Court repealed Roe v Wade. And just like that, nearly my entire final chapter, Reproductive Alternatives, became moot in some parts of the U.S.

I can’t help but wonder, if in states like Texas and Indiana, genetics classes will also skip my book’s earlier coverage of basic prenatal development. Many a politician seems utterly flummoxed by the distinction between an embryo and a fetus, and when certain things happen during a pregnancy. South Carolina senator Tim Scott recently commented that human gestation is 52 weeks. Perhaps he was confusing women with camels or donkeys.

I read Dobbs v Jackson Woman’s Health Organization, rather than relying on media summaries, and searched terms to get an idea of the level of familiarity with biology in the decision. It didn’t take long. Zero hits for stages of embryonic and fetal development, and for techniques other than IVF. No mention of gamete intrafallopian transfer (GIFT), preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD), zygote intrafallopian transfer (ZIFT). (See Repealing Roe: A View from a Long-time Biology Textbook Author, for details.)

Compared to the unintentional otherism, ableism and racism in my textbook writing, interfering with the rights of women to control what happens to their bodies and to access the technologies that science spawns to manage reproductive health, is far worse.

When I began this latest textbook revision, I was stunned at the yellow flags. But now that I’ve finished, I love that my publisher hired experts to analyze my every word and phrase, to make sure that I am effectively communicating the science while seeing situations from viewpoints other than my own. Changing terminology to make the science more accessible is much more than political correctness. It is vital for science literacy.

Ricki Lewis has a PhD in genetics and is a science writer and author of several human genetics books. She is an adjunct professor for the Alden March Bioethics Institute at Albany Medical College. Follow her at her website or Twitter @rickilewis