Those suffering in the dark and in the cold are not gluing themselves to artworks.

Hungry people don’t care if some guru sanctified the seeds before planting.

Families unable to pay their bills would welcome a new factory in their town.

Politicians who preach their virtue vision to an activist minority won’t get much support.

After 30 years of squandering the peace dividend, deindustrialising economies and ignoring facts and evidence in their ideology-driven policies, Western leaders are starting to realise the need for hard decisions, compromising perfect world dreams of tomorrow for a better reality today. After two years of global pandemic, an energy crisis in Europe, global food insecurity and inflation, we can no longer continue to promise a docile public the myth of zero risk, free money and a world of rainbows and butterflies. Leaders have to return to risk management where not everyone gets what they want but they could get what they need.

This is the third part of a series that looks at the Industry Complex. Environmental activism has become an inflexible ideology that has integrated a strict anti-industry, anti-capitalism, degrowth philosophy into its dogma to the point where industry has been delegitimised (tobacconised) from policy dialogue by intolerant rhetoricians. Cleverly imposed on policymakers as virtue politics, environmental-health activists have relentlessly pushed consumers and economies (particularly in Europe) to the edge of a cliff. Giving extremists everything they want is not good long-term strategy in a liberal democracy but policymakers seem handcuffed now to a series of tools and concepts that make resistance quite challenging. Such fundamentalist dogma could only be disarmed by the return to a pragmatic realism in Western politics.

Idealist virtue politics has to be seen for what it is: the wrong policy approach at the wrong time.

It is time for a return to Realpolitik

It is time for regulators to grow a pair and stand up to these outspoken voices of moralising revulsion and intolerance from activist quarters. It is time for them to start doing their job: making the hard decisions and managing risks rather than promising a world of zero risk to a docilian public that has come to expect simple solutions to complex problems. It is time for a return to Realpolitik – of making the best choices from a finite list of options and circumstances rather than continuing their false promises that someone else will have to pay for.

Realpolitik has rarely been used in policy discussions since the end of the Cold War. Indeed the West has enjoyed a peace dividend since the fall of the Berlin Wall which has allowed Western leaders to uncompromisingly pursue their ideals, pay for any consequences of bad decisions and pretend the milk and honey would flow indefinitely. This Western hegemony had few far-away threats and the electorates came to expect to be given everything they wanted. And we could afford it (… until the pandemic).

It is not a new concept. The term “Realpolitik” was in use several decades before Bismarck (commonly referred to as the father of Realpolitik). It was developed by Ludwig von Rochau who tried to introduce Enlightened, liberal ideas, post 1848, into a political world that was embedded in less rational cultural, nationalistic and religious power dynamics (much like the green dogma pushing many Western political spheres today). Realpolitik is often best understood by what it is not: it refers to decisions not made solely on issues of ideology and morality. In other words, Realpolitik refers to pragmatic decisions based on best possible outcomes and compromises (something done when leaders have to face unpleasant realities). Ideologues can easily ignore scientific facts when imposing their power but Realpolitikers will follow the best available science while appealing to reason.

- In agricultural policy, the EU Farm2Fork strategy is based on ideology and morality (that organic is morally better and not industrial-based). But given the recent food inflation and the threats to global food security, a more practical, rational strategy that would focus on sustainable intensification might be a better choice.

- In energy debates, European leaders stupidly gave their loud, activist minority what they wanted (closing nuclear reactors and abandoning fossil fuels) with no pragmatic alternatives or rational transition plan. A Realpolitiker would not have shut down the nuclear power stations until the energy transition was safely achieved.

There are moves to undo some of the more stupid purely ideological strategies in the Green Deal, but Europe might have to wait for blind, uncompromising ideologues like Frans Timmermans to quietly leave the EU stage. For European consumers, this can’t come soon enough.

Precaution versus Realpolitik

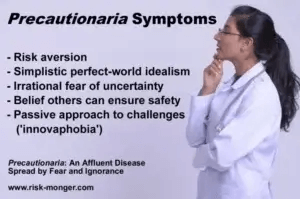

The precautionary principle appeals to an ideologue’s view of the world, unwilling to settle for anything less than perfect. Under the European Environment Agency’s version of precaution (the reversal of the burden of proof), if a technology, substance or product cannot not be proven to be safe, precaution must be taken. Safe and certain are absolutes and advocates have been quick to call for precaution for miniscule exposures to suspected hazards (see the whole endocrine disruption campaign). Actual evidence or reason are not necessary to justify moral-based, ideological decisions.

But should we let perfection be the enemy of the good? Precaution has led to the removal of many highly efficient technologies and substances because regulators were demanding 100% safe. In cases like banning certain neonicotinoid insecticide seed treatments to prevent some concocted bee apocalypse, the alternatives have proven to be worse than the banned substance and many farmers simply abandoned vulnerable crops like oilseed rape (making the situation worse for the bees).

I have argued that we should aim for safer rather than safe. Safer is something risk managers in industry measure and continually strive for while safe is an emotional ideal that cannot be measured or, for that matter, reached. We will never have safe, but we can always strive for safer. This is where a more pragmatic, Realpolitik approach would be more successful than any arbitrary risk aversion. We saw the collapse of the zero-risk precautionary approach after two years of COVID-19 lockdowns that destroyed communities and economies while increasing mental health and domestic abuse issues. Today we have accepted that we have to live with a certain number of coronavirus infections and decisions have become more pragmatic, risk-oriented and rational. We won’t be 100% safe, but we can continually strive to be safer.

Realpolitik accepts that a perfect world is a pipe dream. Freed from the shackles of seeking the totally safe, they get to work on risk management, reducing exposures to as low as reasonably possible (achievable) and making the world (products, substances, systems…) better – safer. They seek a world with lower risks for more people, not zero risks for all people. We need to turn away from the fundamentalist activist mindset and adopt a more industrial, scientific approach (as seen in product stewardship): of continuous improvement, constant iteration and technological refinement.

We cannot afford to continue with this luxury ideology of totally safe codified in the hazard-based, precautionary approach to policy. We need chemicals that can disinfect, pesticides that can protect plants, plastics that can prevent foodborne risks and energy sources that can keep the lights on. Blanket precautionary bans based on narrow ideologies (like the irrational demand for natural substances only) and arbitrary restrictions (eg, that exclude engaging with corporations) create needless shortcomings and hardships we should not be imposing on the most vulnerable.

Engage with stakeholders who can make a difference

Realpolitikers would not be dissuaded from engaging with industry actors (especially as they have access to key technological solutions). They would not tolerate the righteous tobacconisation approach of the ideologues – of excluding the stakeholders with the greatest options and capacities. Just imagine if, when the first COVID vaccines were shown to be relatively effective, governments then declared that corporations must not be involved in the development and implementation of the vaccines. That would be pure stupidity. But this is exactly the type of nonsense we hear from agroecologists who demand that industrial-based research technologies be excluded from farming practices in developing countries. I suppose we need more famines before Realpolitik returns to agricultural discourse.

We are in a world in crisis, craving innovative solutions to serious problems. Innovation entails risk-taking, iteration and continuous improvements. The industrial, capitalist approach rewards innovative thinking (while the precautionary mindset abhors any uncertainties that such innovations could lead to). The present leadership in Brussels, fixated on their Green Deal “save the world” myopia, are the wrong people to lead us out of this crisis (of their own making).

Last year we saw what I would only hope to be the last dying gasp of the precautionary mindset dominating our regulatory thinking. In the early days of the COVID-19 vaccine rollout, there were several cases of blood-clotting that might have been associated with the vaccine. Several regulators, including European Commission Vice-President, Paolo Gentiloni, called for a precautionary halt, particularly of the AstraZeneca jab, until citizens could be certain of the vaccine’s safety. Given the benefits of the vaccine and the lockdown fatigue, a more pragmatic policy response was adopted (drowning out the precautionista protests, but a bit late for AstraZeneca). Could we have enjoyed the benefits of mRNA vaccine technologies if two years of pandemic horror had not woken us from our precautionary slumber? The same technology is now looking into cancer treatments – should this be banned?

A return to Realpolitik is a return to risk management, turning away from several decades of zero-risk precautionary uncertainty management. Such a policy approach prevails when the benefits are so highly in demand with the need for innovative solutions suffocating any irrational fear from uncertainties. An unfortunate few may suffer consequences from a vaccine but a practical, risk management approach would put those risks into a rational perspective (and continually seek to lower those risks).

We actually were never able to afford the perfect-world demands of these precautionary ideologues – affluent righteous zealots who assumed everyone deserved the same benefits they enjoyed. But now the bills are piling up and are demanding hard-headed, practical solutions. It is, indeed, time to move away from a the era of virtue-driven politics and return to Realpolitik.

How to rectify this mess

As readers of this site know, I draw a clear connection between the rise of the use of the precautionary principle with an activist hegemony and the shift away from innovative-friendly policies. This goes hand-in-hand with the anti-industry narrative that is pushing Western societies to a post-capitalist, degrowth regulatory environment. But the present energy, food and public health crises have pierced a gaping hole in the activist campaign balloon, deflating their idealism. So how do we now put Realpolitik back to the centre of policy thinking?

I have argued that industry should get up and walk out of the EU policy process unless the European Commission introduces some fair procedures applied equally to all stakeholder groups. I have also called for a White Paper that can articulate a clear guidance for the risk management process (at the moment it seems like the precautionary principle is seen, erroneously, as the only risk management tool). We need a post-COVID analysis of the failures of precaution and the role of scientific advice. There also should be some guidelines and weighting on the level of influence some NGOs should be allowed to have on the policy process. Too often today groups that represent less than 10% of the European electorate are allowed to drive most European policy … with no regard for the interests of industry, consumers and economic reality.

Industry also has to stand up for itself. The hate campaigns against companies, against capitalism and against innovative solutions need to be countered. For too long they have stayed silent while ethically-challenged zealots spread their lies and agenda against them. What industry considered as diplomatic engagement has now become timid defeatism. Their science needs to be considered on the basis of the facts and data they present, not on the source of funding. When attacking industry becomes an easy excuse for policymakers, then these showmen need to be called out for that; they need to know there are consequences for applying processes and decisions that go against the interests of consumers and the economy, that go against reason and only affirm their hateful, destructive ideologies. Industry actors have to be less polite and diplomatic. Being respected doesn’t win points in the policy arena.

Europe is becoming less competitive, less conducive to research, less productive and less successful on many industrial fronts. Companies are now facing unnecessary costs and restrictions, many are leaving and producing or researching in other parts of the world, consumers are paying more and getting less. Farmers are working harder for lower yields (and increased food imports). Europe is losing out because of bad policies that have been rooted in an anti-industry, anti-technology, anti-growth ideology.

With the present economic, social and environmental threats, this is not the time to tolerate the hateful, closed-minded environmental dogmatists. We need our leaders to back to Realpolitik – not seen since the 1980s – of pragmatic solutions, creative thinking and open-minded compromises.

David Zaruk has been an EU risk and science communications specialist since 2000, active in EU policy events from REACH and SCALE to the Pesticides Directive, from Science in Society questions to the use of the Precautionary Principle. Follow him on Twitter @zaruk

A version of this article was originally posted at Risk Monger’s website and has been reposted here with permission.