In July 2015, Michelle (Shelley) McGuire, a nutrition professor and lactation expert then at Washington State University (WSU), was targeted by anti-GMO activists for allegedly colluding with Monsanto to defend the company’s herbicide Roundup.

39 other independent scientists from public universities all over North America had faced similar accusations for coming out as advocates for crop biotechnology, but McGuire had not jumped into the GMO debate. Rather, she and her research team challenged the popular but unsubstantiated claim that traces of the weed killer glyphosate (the active ingredient in Roundup) were found in breast milk and posed a threat to infants.

The anti-GMO website Sustainable Pulse called McGuire’s work “…. a desperate attempt …. to come up with some data to save …. Roundup …. from public crucifixion.” U.S. Right to Know (USRTK), a virulently anti-biotech group funded by the Organic Consumers Association, labeled her a Monsanto shill and a bad scientist, someone more interested in a paycheck from “big ag” than the health of children—including her own. At a scientific conference last month, McGuire shared new details about the harassment she endured at the hands of anti-GMO activists who saw her research as a serious threat to their efforts to ban glyphosate.

McGuire recounted her story to the Genetic Literacy Project in hopes of communicating an important message to the public. Anti-GMO groups, she said “…. will do and say whatever they have to to get their way, even if it’s a lie. I actually wanted to know if there was glyphosate in human milk, and they tried to take me out because [my] answer wasn’t what they wanted.”

Recap: Moms Across America publicizes faux glyphosate-in-milk study

In 2014, Moms Across America (MAA), an anti-GMO, anti-vaccine activist group, published what it claimed was a pilot study, which purportedly showed that the commonly-used herbicide glyphosate was found in breast milk. The group said its study provided evidence that the herbicide bioaccumulates in the human body and as a result could cause“…. endocrine (hormone) disruption, cancer and neurological disorders” in children. The story was widely picked up by the mainstream media, garnering hysterical headlines around the world and promoted by the blogosphere, although it was debunked by the science press.

McGuire contacted MAA founder Zen Honeycutt in May 2014 and requested the underlying data from the study (how the samples were collected, the age and time postpartum of the study subjects and the analytical methods of the study), hoping to evaluate the results. However, she was told MAA hadn’t collected such data.

McGuire then launched her own research project in an attempt to reproduce MAA’s study—but she couldn’t. The preliminary results from her research, which McGuire presented at a Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology (FASEB) meeting, suggested that “…. glyphosate does not show up in mother’s milk, or is below the detection limit of a very sensitive, newly-developed assay,” as science writer Kavin Senapathy wrote in a 2015 GLP article.

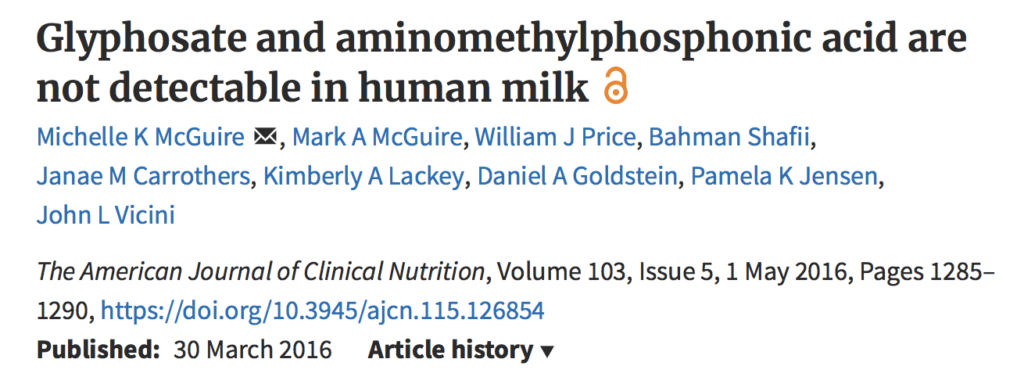

The following year, McGuire and her colleagues published their peer-reviewed findings in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition:

Our data provide evidence that glyphosate and AMPA [the metabolite of glyphosate] are not detectable in milk produced by women living in this region of the US Pacific Northwest. By extension, our results therefore suggest that dietary glyphosate exposure is not a health concern for breastfed infants.

Origins of the controversy

Little did McGuire realize that she had an unintended connection to the flawed MAA study. Back in October 2012, McGuire received an email from a man who identified himself as Gill Rowlands, though the name in the “From” field was “David Rowlands.” Rowlands described himself as a Welsh (Wales) farmer and wanted to know if glyphosate ever made its way into breast milk. McGuire had never investigated the question, because “that’s not my area of research,” she told me on the phone. “I don’t work with pesticides.”

But she thought it was a good question, so she searched PubMed, a research database maintained by the National Institutes of Health, to see if any other scientists had looked for glyphosate in breast milk. She found no studies on the topic. She reported that back to Rowlands.

It turns out the man she was corresponding with was Henry Rowlands, the publisher of Sustainable Pulse, a popular anti-GMO website. Rowlands is an activist who would later arrange the funding and laboratory evaluation for MMA’s faux glyphosate breast milk pilot study. Rowlands used his father’s email address to contact McGuire.

Not knowing who Rowlands was, McGuire cc’d her husband, a dairy scientist at the University of Idaho (where Shelley McGuire is now a professor) named Mark McGuire, on the email thread with Rowlands. Mr. McGuire studies growth hormone in dairy cattle, and Monsanto had previously funded some of the growth hormone research done in his lab. He reached out to his contacts seeking an answer to Rowlands’ question. The Monsanto researchers, Daniel Goldstein and John Vicini, said the company had never studied glyphosate in breast milk, but they would be interested in looking into it. However, the discussion about a possible study stalled until the spring of 2014.

Meeting with Charles Benbrook

In early 2014, Charles Benbrook, an agricultural economist also then at WSU, contacted McGuire and invited her to have coffee. They had similar research interests, he said. Benbrook is also a well-known critic of Monsanto and much of his research has been funded by organic food companies. Just like Rowlands, Benbrook wanted to know if glyphosate could get into breast milk. He also asked how McGuire felt about organic farming and what she knew about Monsanto and Roundup.

The meeting was really strange, according to McGuire. “Why are you asking me this?” She said on the phone, recounting the conversation with Benbrook. “But in hindsight we know that all these folks are connected.” McGuire’s observation makes sense in light of the fact that Sustainable Pulse promotes Benbrook’s research. Emails released to the public also provide evidence that Rowlands and Benbrook have corresponded about the environmental impact of glyphosate in their attempt to demonize the herbicide.

When the MAA pilot study was released online that spring, Monsanto reconnected with McGuire and asked her to collaborate on a study to see if glyphosate could be detected in breast milk, with Rowlands copied on the email. At this point, no adequate, long-term independent tests had been undertaken to ensure that glyphosate herbicide formulations were not persistent, bio-accumulative or toxic. Interestingly, MAA requested this sort of validation of their results. In the press release for their pilot study, MAA said it wanted

…. testing [that] would include the outcomes most relevant to children’s health. The U.S. Congress should supply funding for urgently needed long-term independent research on glyphosate herbicide formulations, including their health effects, how they get into the human body ….

Avoiding a conflict of interest

As a lactation specialist at a public university, McGuire was perfectly suited to carry out the study. But there would be accusations that collaborating with Monsanto would bias the results, so she acknowledged that the company gave her and her husband each a $10,000 unrestricted grant, money with no strings attached. “The university research office wouldn’t have signed off on [the grant] otherwise,” McGuire said.

For the study, McGuire collected milk and urine samples from 41 women, and the Monsanto team developed a testing method, called an assay, that was sensitive enough to detect glyphosate in breast milk. A third-party laboratory called Covance then tested the samples McGuire’s team collected using the assay developed by Monsanto, again to head off accusations that she was paid to produce a study favorable to the company. McGuire added that Covance had “every incentive” to find glyphosate in the milk samples, “because everyone would have started sending them milk samples. They could have had quite the business analyzing milk for glyphosate.”

The lab was unable to detect any glyphosate, however, and McGuire presented these preliminary results at the Montana Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology (FASEB) meeting in July 2015. But this is where things took a strange turn. “It was a closed scientific meeting, where the abstracts were not publicly available,” McGuire recalled. WSU put out a press release about the research the day McGuire presented the findings, but the brief article from the university did not discuss the “…. full details of the method or the limits of quantification used” for the study, as Sustainable Pulse eagerly pointed out in a blog post published the day after McGuire’s presentation.

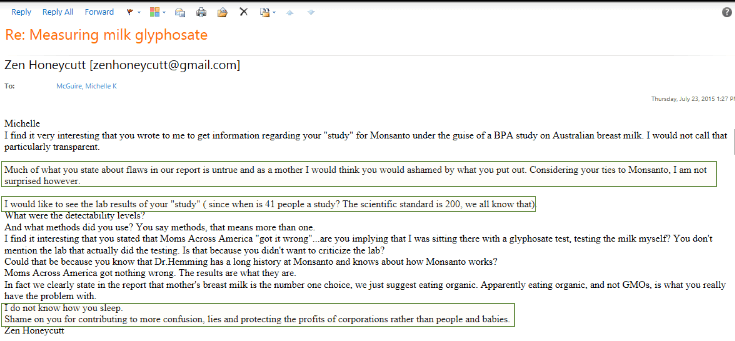

Nonetheless, within an hour of giving her presentation at the meeting, McGuire received several angry calls from MMA’s Zen Honeycutt. Rowlands and Honeycutt also began sending harassing emails to McGuire. “I do not know how you sleep,” Honeycutt wrote in one email. “Shame on you for contributing to more confusion, lies and protecting the profits of corporations rather than people and babies.”

Hacked presentation?

These reactions were disturbing, because Honeycutt and Rowlands were not in attendance and could not have otherwise known about the research results that quickly. McGuire also said the activists had obtained a copy of the Powerpoint presentation she used at the meeting, which she had not released to the public.

The intimate knowledge Honeycutt and Rowlands had about McGuire’s presentation seems to fit into the timeline of events that is already known. She presented the results of her preliminary study on July 23, 2015, and on July 27, 2015, USRTK submitted a FOIA request to WSU for McGuire’s emails, looking for any interaction she may have had with Monsanto. It was at this point McGuire and her team realized who Henry Rowlands is and why he may have reached out to her in 2012.

Rowlands may have been “fishing for someone to do the [MAA] study,” McGuire speculated. This also could have been why Benbrook arranged to meet with her in early 2014 and asked her how she felt about organic farming and Monsanto.

Call to USRTK

Over the next three years and in 40 installments, WSU sent McGuire’s emails, 12,000 documents in all, to USRTK under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). McGuire spent roughly three hours per installment with the lawyers so she could identify which information USRTK legally would have access to. In total, McGuire estimated she spent a month going through emails instead of conducting her research.

Hoping to avoid an unjustified scandal for WSU, McGuire called Gary Ruskin, the co-founder of USRTK, when she heard about the extensive FOIA request. “‘I will send you whatever emails you want, but this list is huge,’” she told him. Ruskin told McGuire that he knew she was hiding something and USRTK would find it. “Then he hung up on me,” McGuire recounted. “He was as rude as he possibly could be.”

Fallout at WSU

McGuire said the worst part of the whole affair was how WSU reacted to the accusations MAA, Rowlands and USRTK leveled at her. When the FOIA request first came through, McGuire went to her department head at WSU for input on the situation, explaining that she was unprepared for such a vicious attack.

“What do you expect?” he replied, “Monsanto is a horrible company.” His answer shocked her, because she did not believe it accurately described the company; it was a simplistic generalization about a complex research-based corporation. But McGuire said the situation got worse. She was told by university officials not to rebut the accusations being made against her in public.

It wasn’t an official gag order, but I was asked in no uncertain terms not to speak to anybody …. As academics, we have to engage, because otherwise the public only knows what they read and hear [from activists]. If we’re being encouraged by our universities to keep our mouths shut, then this is just going to get worse.

Cameron J. English is the GLP’s senior agricultural genetics and special projects editor. He is a science writer and podcast host. BIO. Follow him on Twitter @camjenglish