In three court cases, juries have ruled that glyphosate, sold in non-generic form under the trade name Roundup and made by Monsanto (now a division of Bayer), caused the cancer of workers who applied the herbicide. The cases did not address the issue of whether glyphosate might cause harm to humans exposed to parts per billion or parts per trillion traces of the pesticide found in foods. Regulatory agencies around the world have addressed this issue, however.

Courts do not determine scientific fact

A jury decision, while headline-grabbing, is not a substitute for scientific research and the judgment of independent scientists at government regulatory agencies. Juries have often gotten science wrong, most infamously the decision in the ‘Scopes Monkey Trial’, in which high school teacher John Scopes was found guilty of teaching evolution, which creationists contended was not scientifically supported.

The most challenging question for juries is whether a particular chemical is the cause of cancer or another illness. Our tort system relies on lay juries attempting to make sense of complicated and often contradictory medical studies and expert opinions. Science rarely renders absolute ‘verdicts’; it addresses probabilities. It’s been shown time and again that when juries are asked to evaluate studies that conclude ‘substance x is unlikely to cause cancer’, they almost always assume the worst, that because the study did not definitively conclude it ‘does not’ or ‘could not cause cancer’.

But no group of scientists writing a reputable study would ever use the kind of absolute statements that would put a jury at ease. Hence, when jurors have even slight doubts, they frequently rule against a chemical and its manufacturer, and for an aggrieved (and often fatally ill) plaintiff, even when the evidence is slim or close to nonexistent.

For example, in 2018, a Missouri jury awarded $4.69 billion to women with ovarian cancer they claimed was caused by Johnson & Johnson baby powder. In 2018, J&J was ordered to pay $117 million to a New Jersey man with mesothelioma, and $25.7 million to a Los Angeles woman with the same cancer.

Medical studies on the relationship between ovarian cancer and talcum powder use on the genitals are not at all definitive, however, with none showing a strong association and most showing no association at all. The National Cancer Institute says the evidence is not strong enough to conclude that talcum powder causes ovarian cancer, and the American Cancer Society notes that any existing risk is likely small, and that research is ongoing. As Popular Science has reported, the company is appealing those verdicts.

Takeaway: What the legal system considers enough evidence to establish that exposures causes illness is different from the standards of science—and trying to fit the two together can be hazardous. Which brings us back to the controversy over glyphosate.

What do regulators and investigatory agencies conclude?

Even though extensive research has been done on glyphosate, there remains intense debate online and in the media about whether the herbicide poses a health threat to agricultural workers or the general public as a result of residues in food.

At least 15 regulatory and research agencies have conducted long-term studies, reviews and assessments to determine whether glyphosate, when used as labeled, increases the risk of certain cancers. They are unanimous in one finding: There is no evidence that glyphosate poses any harm to consumers worried about trace residues in their food. Despite many blogs by anti-biotechnology advocacy groups touting ‘studies’ (usually not very scientific, such as here, most recently) finding glyphosate in beer or cereal at the parts per billion or parts per trillion level, or finding traces of glyphosate in blood or urine, there is no scientific study that suggests those trace residues pose any threat to humans.

The Genetic Literacy Project summarized and analyzed the findings of the world’s top regulatory and chemical research organizations in a GMO FAQ posted here and on our GMO FAQ site. To date, every regulatory agency that has evaluated glyphosate has concluded that it is safe if used according to label specifications and does not increase cancer risk, particularly if glyphosate residue is found on food, including produce.

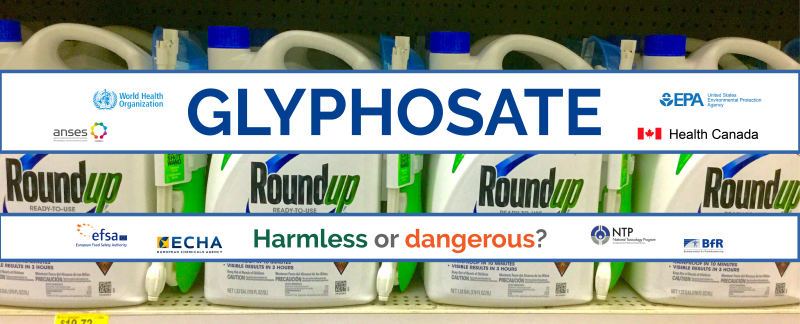

The infographic summarizes the conclusions of the most prominent agencies that have evaluated the studies. The global consensus is concisely expressed in January 2019 by Health Canada, the oversight agency that most recently issued a re-review of the controversial pesticide: “No pesticide regulatory authority in the world currently considers glyphosate to be a cancer risk to humans at the levels at which humans are currently exposed,” Health Canada wrote.

In addition to the many assessments and evaluations, we included a link to a large and long-term study known as the Agricultural Health Study that monitored the incidence rate of multiple cancers in 54,251 pesticide applicators in the United States, including 44,932 who had handled glyphosate between 1993 and 2016. The study found no association between glyphosate and any solid tumors or lymphoid malignancies overall. The data is ambiguous in workers exposed at very high levels. These findings coincide with data collected in farm country. Regional differences in the usage of glyphosate in US counties can vary by more than 20-fold, yet many of the counties with the highest usage of glyphosate have a relatively low incidence of NHL.

The only outlier is the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), which does not look at the risk posed by a particular chemical. Rather, it examines hazard—whether a substance might cause cancer at any exposure rate or dose, even unrealistically high ones. Under a hazard designation, almost any substance can be judged toxic, even water, if the dose is extreme and the exposure time is long enough.

Over more than 40 years, the agency has assessed approximately 1,000 substances and activities, ranging from arsenic and beer and coffee to sunbathing and hairdressing. Over that time, it has found only one agent or activity that was “probably not” likely to cause cancer in humans. In 2015, IARC put glyphosate in the category “probably carcinogenic to humans”—along with red meat, drinking hot beverages, and yes, going to the hairdresser or barber. But there was less evidence of glyphosate’s carcinogenicity than the agency found for bacon, salted fish, oral contraceptives and wine, among many examples. Its ‘hazard’ conclusion has been used to support proposed bans on glyphosate and was the central piece of evidence in the two recent trials.

The absurdity of the hazard-risk distinction, and glyphosate’s low risk profile relative to dozens of foods, chemicals and behaviors humans regularly encounter every day with no fear, is almost totally absent from the popular and media discussion of whether glyphosate might pose any serious danger.

For context, it’s also important to note that IARC is a sub-agency within the World Health Organization of the United Nations; it is not WHO itself, as many anti-chemical activists and some in the media represent. Three other WHO agencies including WHO itself performed risk assessments on glyphosate and repudiated IARC’s findings, but as our infographic makes clear, their far more comprehensive analyses are often ignored in media accounts or not even considered by juries.

In the infographic below, we summarize the most respected research. To believe that glyphosate causes cancer, one would have to believe in a coordinated world-wide conspiracy involving agencies in the US, Canada, Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, New Zealand and three separate divisions of WHO to suppress evidence of glyphosate’s dangers.

Click on the bolded conclusions to take you to the document issued by the regulatory or research agency.

Click here for a downloadable .pdf version of this infographic.

Kayleen Schreiber is the GLP’s infographics and data visualization specialist. She researched, authored and designed this infographic. Follow her at her website, on Twitter @ksphd or on Instagram @ksphd