Many people are aware—and properly protective—of the vast stores of information contained in their DNA. When DNA samples were collected in New York without consent, some went to great lengths to have their DNA expunged from databases being amassed by the police.

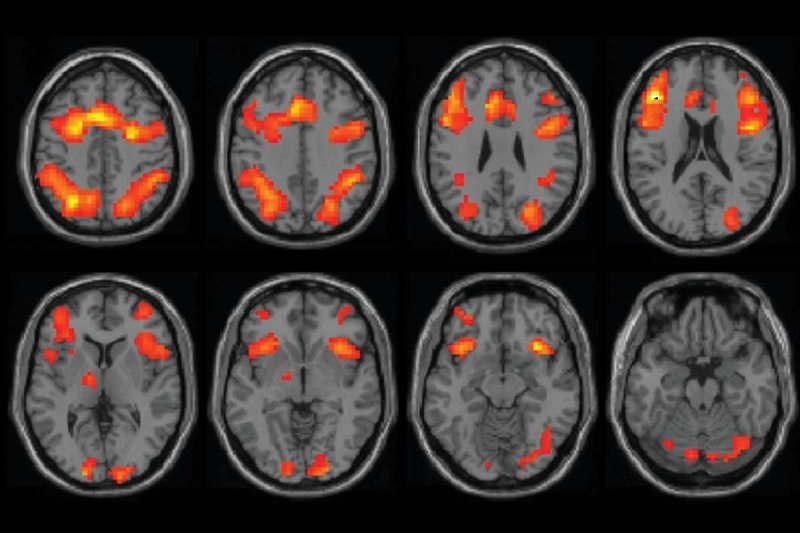

Fewer people are aware of the similarly vast amounts of information in a brain scan, and even fewer are taking steps to protect it.

…

There may be good and bad reasons to use a brain scan to make personalized predictions. Good or bad, wise or unwise, the research is already being conducted and the brain scans are piling up.

…

Could a forensic brain imager identify you as unlikely to complete drug treatment and thus a bad candidate for diversion? What if we could predict your future behavior by similarities that your fMRI networks share with those of psychopaths who had been analyzed and whose data now resides in a database?

…

These are questions that brain imagers, legal experts, ethicists, and the public should be debating. Scenarios that may seem far-fetched right now raise troubling questions that ought to be anticipated. Genetic testing controversies of today can serve as models for how we think about the potential uses and misuses of brain imaging.

Read full, original post: Why We Need Guidelines for Brain Scan Data