The conventional theory among historians today attributes the origin of the Ethiopian Jews to a separatist movement that branched out of Christianity and adopted Judaism between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries (e.g. Quirin, 1992a, 1992b; Shelemay, 1989; Kaplan, 1995). The theory essentially holds the Ethiopian Jews to be the descendants of indigenous non-Jewish Ethiopians, and their belief in ancient Jewish descent to be just a matter of myth and legend. Proponents of the theory have been praised for being “thought-provoking” (Waldron, 1993) and for “demythologizing” (Gerhart, 1993) the history of the group. Consequently, scholars, and historians in particular, have been steered to ignore the compelling evidence for the ancient origins of the group.

I will present the historical evidence which, with the support of crucial genetic findings, strongly suggests that today’s Ethiopian Jews are the descendants of an ancient Jewish population. This study reinforces recent reviews of the DNA studies of the Ethiopian Jews (Entine, 2007) that have already pointed to major flaws in the traditional historical perspective. Furthermore, the latest research further suggests a strong historical affiliation between the Ethiopian Jews and Northern Sudan that is little discussed in literature. The paper analyzes the history of the Jews of Ethiopia in context of their peripheral geography in the Lake Tana area and the Semien.

The Beta Israel

Until they were forced to leave Ethiopia in the 1980s, Ethiopian Jews lived in small villages scattered in the northwestern region of the Ethiopian plateau around Lake Tana and in the Semien mountains area. They traditionally referred to themselves as the Beta Israel, and were referred to by other Ethiopians as Falasha, meaning “strangers” in the indigenous Semitic language Ge’ez. Thus, the term Beta Israel will be used throughout this article to label the community.

The community has venerated the Old Testament of the Ethiopian Bible and its religious language has been Ge’ez. Today, the Beta Israel show closest resemblance in external cultural characteristics to their surrounding Habash, i.e. the ethnic category that encompasses the Amhara and Tigray-Tigrinya populations. And although both the Habash-Christians and the Beta Israel claim royal descent from the time of King Solomon and Queen Sheba, an important difference exists (Entine, 2007, p.148-9). While the Christians claim descent from King Menelik—the offspring of Solomon and Sheba in Ethiopia—the Beta Israel claim descent from first-generation Israelites from the tribe of Dan who some believe accompanied Menelik as guards of honor.

To start with, the geographical definition of Ethiopia in historical sources must be addressed for it has distorted major studies on the history of the region. It wasn’t until recently that scholars realized that the name Ethiopia, in ancient and medieval sources, denoted the Nile valley civilization of Kush, also known today as ancient Nubia, in what is today Northern Sudan. On the other hand, the geographical area that encompasses the modern country of Ethiopia had in the past housed the ancient kingdom of Aksum, which developed in the northern parts of the plateau, and was sometimes referred to as Abyssinia. It is also worth mentioning that all of the Biblical, and a significant portion of the ancient, references to Ethiopia, or Kush, predate the establishment of Aksum in the first century CE.

As I have argued in a former paper (Omer, 2009a), analyzing the history of the Beta Israel within the boundaries of the contemporary country of Ethiopia is a problematic approach. That is because the political boundaries of the modern day countries of Sudan and Ethiopia were only defined towards the early twentieth century. However, even after the boundaries were specified, the Beta Israel settlements remained at the periphery and far from the interior of today’s Ethiopia, which is close to the western border region with Northern Sudan.

The political boundaries between the two states had remained, for the longest part of history, fluid and undefined in many areas. It was mostly the twentieth century borderline that defined the contemporary identity of the Beta Israel population as Ethiopian, and distinguished them from the populations of the flat plains of the Sudan, to the west. In other words, the Beta Israel have always represented a periphery population that, in the context of history, can never been seen as integral element of today’s Ethiopia.

Theories of history

Before proceeding further, I will present a brief overview of the hypothesis that the Beta Israel emerged out of Ethiopia’s Christianity. The hypothesis is best argued by Quirin (1992a) and Kaplan (1995). Quirin’s argument is based on the premise that the Beta Israel identity has “emerged out of a differential interaction with the Ethiopian state and dominant Abyssinian society” (1998, p. 1). Kaplan (1995) follows the same line of argument and concludes that “their ‘Judaism,’ far from being an ancient precursor of Ethiopian Christianity, developed relatively late and drew much of its inspiration from the Orthodox Church” (p. 157). They essentially argue that the religious substance of the Beta Israel has been adapted from the Jewish character already found in Ethiopia’s Christianity. Salamon (1999) also emphasizes the Christian roots of the Beta Israel, yet she leaves the question of the group’s actual origins open to question. She argues that they “constructed their identity in reference to their Christian neighbors, rather than to a Jewish ‘other’” (p. 4).

Lack of neutral analysis to the shared similarities between the religious traditions of the Beta Israel and that of the Ethiopian Church has been a major problem in the study of the group. Having said this, it should be noted that Ethiopian Christianity appears to be more influenced by Judaism than vice versa. Gatatchew Haile (as cited in Tibebu, 1995, p. 11) states:

Only a Christianity of a nation or community that first practiced Judaism would incorporate Jewish religious practices and make the effort to convince its faithful to observe Sunday like Saturday. In short, the Jewish influence in Ethiopian Christianity seems to originate from those who received Christianity and not from those who introduced it. The Hebraic-Jewish elements were part of the indigenous Aksumite culture adopted into Ethiopian Christianity.

Also, as Kessler (2012) points out, the theory does not indicate how the Beta Israel gained intricate comprehension of Jewish material encompassing pre-rabbinical principles based on the books of Enoch and Jubilees. In essence, the sum of Christian influences in Beta Israel religious traditions, which we should take great care not to exaggerate, may reflect nothing much more than the struggles of a Diaspora Jewish community at preserving whatever was left of its steadily vanishing heritage. Poverty, instability, persecution, and illiteracy across the centuries would have certainly caused the loss of any significant authentic Jewish scriptures. However, this should not deny the survival of the fundamental aspects of the Jewish identity and religion among the Beta Israel.

Moreover, a basic question that Kaplan (1995) and Quirin (1998) do not address is: Why would Christians become Jews? As Teferi (2013) explains, converting to Judaism requires the abandonment of the essence of Christianity (p. 179), which makes a conversion unlikely. The only reasonable suggestion, Teferi indicates, as to why Christians would have become Jewish is if they were forced to (p. 180) convert, which is also unlikely.

Worth mentioning are the accounts of the sixteenth century Christian monks, Abba Saga and Abba Sabra, which have been of major importance to proponents of the traditional Christian origin theory. Quirin (1992a) as well as Kaplan (1995) present the two monks as central figures in establishing the religious institutions of the Beta Israel. This is based on the idea that the monks must have been responsible for introducing monasticism and the clergy system found within the Beta Israel traditions.

This aspect of the argument is problematic for three reasons. First, there is nothing concrete to confirm the historicity of the two monks. Second, a different sixteenth century report suggests that many Beta Israel practiced monasticism prior to the alleged arrival of the two monks (Teferi, 2013, p. 185). The report refers to Jews from Abyssinia (or Aksum) and “their books, their priests and their monks” (as cited in Teferi, 2013, p. 185; Norris, 1978). Third, as stated by Kessler (2012), “Quirin tends to confuse the basic tenets of the Beta Israeli Falashas with the rites and forms of their practices” and “does not appreciate that the religion ‘as it has come down to us’ [as cited in Quirin, 1992a, p. 68]. In essence this means a belief in the oneness of the Almighty, based on the teachings of the Torah (Orit), and a faith in the coming of the Messiah,” which “more than ritual differences – important though they are – distinguish Judaism from Christianity and could not conceivably have been invented by the rebel monks” (Preface to Third, Revised, Edition section).

The Beta Israel and Kush (Northern Sudan)

In order to trace the origin of the Beta Israel, we must start in Northern Sudan, where the oldest evidence for Jews in the Horn of African area points. This is not only important because of the geographical relevance between the Beta Israel and Kush, but also because of the immense evidence that link between the two.

The history of the Beta Israel in context of their neighboring ancient land of Kush, in what is today Northern Sudan, has surprisingly not been the subject of a serious investigation. Kessler (2012) is one of very few contemporary scholars who has attempted to elaborate on the connection between the Beta Israel and Kush, and has recognized the tendency among scholars “to underrate the significance of the impact of ancient Egypt and of Nubia or Meroë” (Preface to Third, Revised, Edition section) on development of the African Horn region.

References to Kush appear in the Bible as well as in extra-Biblical narratives and traditions. The Bible mentions directly the presence of Jews in Kush; the book of Zephaniah states (note that Ethiopia in ancient sources referred to Northern Sudan, not to the modern country of Ethiopia): “From beyond the rivers of Ethiopia [Kush], My worshipers, My dispersed ones, Will bring My offerings” (3:10, New American Bible). Psalm 87:4 and Isiah 11:11 make the same indication.

Also, the Bible identifies a number of important Biblical characters as Kushite. In Numbers (12:1), the wife of Moses is claimed to have been a Kushite. Zipporah, Moses’ wife known by name, is commonly described in Biblical traditions as being of Kushite ancestry. In Ezekiel (Exagoge: 60-65) Zipporah tells Moses about her motherland:

Stranger, this land is called Libya [Africa]. It is inhabited by tribes of various peoples, Ethiopians [Kushites], black men. One man is the ruler of the land: he is both king and general. He rules the state, judges the people, and is priest. This man is my father {Jethro} and theirs.

The Midrash Book of Jasher (Hapler, 1921), provides a detailed account of Moses’ journey to the southern kingdom of Kush; including how he gained the admiration of its people (p. 132):

Twenty-seven years old was Moses when he began to reign over Cush [Kush], and forty years did he reign. And the Lord made Moses find grace and favor in the sight of the children of Cush, and the children of Cush loved him exceedingly.

What makes Kush central to the study of the Beta Israel is that it has defined the groups’ identity until medieval times. Rabbi David ben Solomon ibn Zimra, the sixteenth century Chief Rabbi of Egypt, whose acknowledgment of the Beta Israel as rightful Jews has later been of significant importance in their recognition by the world Jewry, states: “those [Jews] who came from the Land of Cush are without doubt of the tribe of Dan…” (as cited in Lenhoff & Weaver, 2007, p. 303).

The identification of the Beta Israel with Kush is best illustrated in the writings of Jewish scholar and traveler Eldad Ha-Dani in the ninth century. Eldad identifies himself as being a citizen of an independent Jewish state “beyond the rivers of Cush” (Hapler, 1921, p. 49). He also identified himself as being of an Israelite origin from the tribe of Dan, and thus his last name Ha-Dani. Eldad’s geographical affiliation and identification with the tribe of Dan strongly corroborate with what is known of the Beta Israel (Omer, 2009b; Epstein, 1891; Schindler & Ribner, 1997, p.2; Teferi, 2013, p. 188-9; Schloessinger, 2009, p. 1-9).

Moreover, Eldad’s description of the ethnic groups and geography of the African Horn region appears to be fairly legitimate and reinforces the historicity of his accounts (Borchardt, 1923-1924). In the course of his narrative, he elaborates on the migration story of his Israelite ancestors—the tribe of Dan—from the time when they left the “land of Israel” (Hapler, 1921, p. 52), passed through Egypt, and finally settled down in “the land of Cush”(p. 53). He states: “The inhabitants of Cush did not prevent the children of Dan from dwelling with them, for we [the children of Dan] took the land by force” (p. 53). The fact that Eldad identifies his people with Kush, and not with Aksum, demonstrates the very strong historical identity bond that ties between the Beta Israel and Northern Sudan. And although scholars commonly view the affiliation with the tribe of Dan in context of other world myths about the ten lost tribes of Israel (e.g. Segal, 1999; Schwartz, 2007, p.1x), some scholars have proposed an actual Samaritan origin for the Beta Israel on basis of a variety of religious and linguistic evidence (Shahîd, 1995, p.94-5; Leonhard, 2006, p.39-42). Hence, tribal Israelite descent amongst the Beta Israel is not unlikely.

Another important twelfth century Jewish traveler, Benjamin of Tudela, writes about independent Israelite cities in mountains in Eastern Africa—in a clear reference to the Beta Israel settlements in the Semien mountains—from which the inhabitants “go down to the plain-country called Lubia [or Nubia]” (Benjamin as cited in Kaplan, 1995, p. 50). Though Benjamin does not refer to Kush, his uses the more medieval name of Northern Sudan, Nubia.

A third, no less significant source, is the fifteenth century scholar, Obadiah ben Abraham of Bertinoro, who discusses trade relations between the Beta Israel and Kush: “They believe them-selves to be descendants of the Tribe of Dan, and they say that the pepper and other spices which the Cushites sell come from their land” (as cited in Abrahams & Montefiore, 1889, p. 195).

Furthermore, archeological findings indicate strong communication ties and travel between Aksum and Kush, starting from the early stages of the Aksumite kingdom (Fattovich, 1975, 1982; see also Phillipson, 1998, p. 24). As mentioned previously, the civilization of Kush predates that of Aksum with more than fifteen hundred years. While Kush was already a flourishing kingdom by 1700 BC, and rose as a Mediterranean empire in the eighth century BC, Aksum did not emerge as a recognizable kingdom until the first century CE. Although the archeology of pre-Aksum, in what is today Ethiopia, reflects a dominant South Arabian culture, the later archeology of Aksum shows stronger and direct cultural influences from Kush (Pirenne, 1967; Fattovich, 1982, 1975).

Furthermore, during the Meroitic period, when Kush was centered at Meroe, from 270 BC- 400 CE, the Kushites conducted extensive building activities east of the Nile. Starting from around the first century, constructions included numerous hafirs and other water sources (Welsby, 1998, p. 128), which indicates the intensification of human movement between the kingdom of Kush and with the, by then, emerging kingdom of Aksum. It should also be noted, in this regard, that Aksum’s only direct-land access to the Mediterranean was through the Sudan.

Kessler (2012) has identified a number of traditional Beta Israel crafts and production practices that are historically associated with the people of Kush; those are domestically made pottery, cotton weaving, basketry, and leatherwork. More importantly is the traditional role of the Beta Israel as ironsmiths, which corresponds with Meroe’s distinctive role in ancient history in the discovery and manufacture of iron. Being rich in ore, the Kushites employed iron in all the different industries of the kingdom including agriculture (Asante, 2012, p. 96).

Given all these indications, the possibility that the Jews who entered the kingdom of Aksum, which did not mature until the first century CE, came from Kush becomes likely. Even though such speculations seem to still fall short of explaining the exceptional affiliation between the Beta Israel and Northern Sudan in medieval references, they pose crucial inquiries regarding the origin of this group.

Finally, in context of our search for the historical, and possibly genealogical, connections between the Beta Israel and Northern Sudan, an important point regarding the physical features of the group must be made. Contrary to what is commonly assumed, and as I stressed formally in an essay (Omer, 2012, p. 1), the Beta Israel do not really look like their surrounding non-Jewish Ethiopians. As a Northern Sudanese myself, I was able to notice that most of the Beta Israel look closer to the people of Northern Sudan in physical appearance, than they do to the non-Jewish Ethiopians. In other words, although a non-Jewish Ethiopian can easily be distinguished from a Northern Sudanese by looks, no distinction can mostly be drawn between an Ethiopian Jew and a Northern Sudanese. The majority of them do not look like the non-Jewish Ethiopians.

On the other hand, and despite the expected difficulty in distinguishing East African specific physical features for people from other places, Western scholar, Leslau (1979), who visited Ethiopia in the 1940s was able to notice some “facial traits” (p. xii) among the Beta Israel, which he mistakenly associates with the stereotypical look of the “Oriental Jew”.

The Beta Israel and Aksum

The traditional Christian origin theory argues that the contemporary Beta Israel developed separately from the ancient Jews of Aksum. Quirin (1992b) states: “The ‘Falasha’ emerged as an identifiable, named group during the period from the fourteenth to the sixteenth century” (p. 203); in agreement, Kaplan argues: “Nothing in the written sources can be interpreted as reliable evidence for the survival of a distinct well-defined Jewish community in Ethiopia for the period from the seventh to the 14th century” (1995, p. 55).

However, historical evidence strongly contradict Quirin’s and Kaplan’s conclusion. To start with, it has been confirmed with certainty that Judaism in Aksum predates the introduction of Christianity, in the fourth century. Kaplan (1995) admits that “the linguistic evidence would seem to clearly indicate that Jewish influences in Ethiopia were, at least in part, both early, i.e., Aksumite, and direct” (p. 19). Linguistic evidence found in translations of Biblical material into Ge’ez, has already shown that a Jewish society had entered Aksum sometime between the first and fourth centuries (Kaplan, 1995, p. 13-20). As a result of this, the influence of Judaism in the Ethiopian Orthodox church has been overwhelming and has no counterpart in the contemporary Christian world. Traditions including circumcision on the eighth day of birth (Ullendorff, 1956), the historical upholding of the Saturday Sabbath (Ullendorff, 1968, p. 109-13), the architectural division system of the Ethiopian church that mimics Solomon’s Temple (Ullendorff, 1968, p. 87-97), as well as a diversity of other features, testify to a powerful former Jewish culture.

Additional evidence comes from the sixth century reign of Kaleb, the fervently Christian king of Aksum who adopted vigorous policies to convert the non-Christian inhabitants of the kingdom. In the early decades of the century, he restored Christianity to South Arabia by defeating its Jewish king. Unfortunately there are no sources to elaborate on his domestic policies towards the Jews; however, a few but significant sources provide crucial indications for the origins of the Beta Israel settlements in the Lake Tana area and the Semien. Some of these sources mention that Kaleb had two sons; one Gabra Masqal and another Beta Israel (Kaplan, 1995, p. 39; Getatchew Haile, 1982). Beta Israel is said to have unsuccessfully attempted to deter Gabra Masqal’s path to the throne. In this account, it seems that the name Beta Israel was used as propaganda to symbolize the disobedience of the Jews to conversion. (Of course the idea that Kaleb himself was a Beta Israel is also subject to speculation).

Also, during the sixth century, the Alexandrian traveler Cosmas Indicopleustes reports on military conflicts between an Aksumite king (probably Kaleb) and enemies in the “Semenai [Semien]”(McCrindle, 1897, p.67); this may indicate that Jewish resistant movements were already being clustered in the indicated area. Another reference from medieval Abyssinia speaks about events taking place around the sixth century, and mentions the name “Falash[a]” (as cited in Kaplan, 1995, p. 39; also see Varenbergh, 1915-16).

By the mid sixth century, Aksum began to decline and struggled to control its northern and peripheral territories. By the late decades of the century, the frontier regions to the north and west of Lake Tana were mostly independent and may have already been inhabited by Jews. From the seventh to the fourteenth centuries, the mentioned areas remained isolated from Aksum, which seemingly explains the decline in references to Jews in Aksumite sources.

Eldad’s reference to his independent Jewish state “beyond the rivers of Cush” (Hapler, 1921, p. 53) during the ninth century seems to point to the same Lake Tana area of the Beta Israel. Writing in the twelfth century, Benjamin of Tudela appears to corroborate Eldad’s account by mentioning independent Israelite cities in Eastern Africa: “And there are high mountains there and there are Israelites there and the Gentile yoke is not upon them” (as cited in Kaplan, 1995, p. 50). It appears that by “mountains” Benjamin is referring to the Semien.

Finally, the Jewish queen Judith, who is deeply situated in Ethiopian history and traditions, is described as coming from a region “west” (Trimingham, 1952, p. 52) of Aksum and ruled Aksum sometime in the late ninth or tenth century, is yet another strong indication of the presence of Jews in this region prior of the fourteenth century. The Christian Zagwe dynasty that succeeded Judith to the throne and ruled until the late thirteenth century is widely described as being of Jewish roots (Briggs, 2009, p. 18). Judith’s possible Jewish background is further enforced by the fact that the dynasty governed from Lasta, which has been a vigorously Jewish area.

Given the various references for Jewish presence in the region across the centuries, there appears to be no persuasive reason to assume that the Beta Israel have emerged as recently as the fourteenth to sixteenth centuries. It is also very unreasonable to suggest that all such historical references to Jewish presence in the designated regions, which greatly correspond with the historical and cultural context of the contemporary Beta Israel, are coincidental.

Genetic evidence

In recent years, DNA studies have shown the conventional historical theory endorsed by Kaplan (1995) and Quirin (1992b) to be very much unreliable. An in-depth analysis of genetic research by Entine (2007, p. 149) states:

The Falasha may have been a rump group that remained true to its historical roots when the Ethiopian king converted to Christianity in the fifth century. For centuries, the Black Jews maintained separate traditions from their Christian countrymen. While most Ethiopians ate raw meat, drank heavily, and rarely washed, the Falasha cooked their meat and were scrupulously sober and relentlessly hygienic.

Although the precise relationship between the ancient Jews of Aksum and the contemporary Beta Israel community has not been clearly understood by geneticists, studies have already confirmed some historical continuity within the group (Entine, interview, July 7, 2013). Thus, the widely accepted theory among geneticists, as proposed by Entine (2007) and supported by research and subsequent studies (Saey, 2010; Ostrer, 2012), suggests that the group was formed as early as the fourth to sixth centuries period. The fact that studies found the Beta Israel to be genetically so diverged from other Jewish communities (e.g. Lucotte & Smets, 1999) may suggest that the group was initiated by Jewish settlers who converted a majority of local people to Judaism more than two thousand years ago (Begley, 2012). Accordingly, Entine (2013) concludes, “That would mean that Ethiopian Jewry predates Ashkenazi Jewry” (interview, July 7); however, this does not necessarily suggest that the Beta Israel descent can be specifically traced to the Fertile Crescent.

Moreover, despite the fact that the genetic distance between the Beta Israel and other contemporary Jewish groups is large, studies have already cited cases of Ethiopian Jews with genetic markers common in other Jewish populations (Hammer, et al., 2000).

The wide range of historical evidence available on the Beta Israel points to the survival of an ancient Jewish heritage within the group. Furthermore, sources suggest the establishment of the Beta Israel settlements in their contemporary Lake Tana locations to be much earlier than the fourteenth to sixteenth centuries period some historians have suggested. In addition, the African ethnicity of the Beta Israel appears to be more complicated than just Ethiopian, and seems to reflect a strong Northern Sudanese element as corroborated by the wide range of mentioned historical observations and the peripheral geography of the population.

We need more historical investigation on the origin of the Beta Israel that is not dictated by concepts of the conventional historical theory. Recent genetic studies have already confirmed an ancient heritage within the contemporary Beta Israel population. Hence, the approach suggested by the traditional historical theory in simplifying the origins of the group to local and former-Christian converts is neither geographically persuasive nor convincing from a historical point of view.

Ibrahim M. Omer is a Research Assistant at California State University Monterey Bay, Visual & Public Arts Department, Museum Studies Program.

View a complete list of REFERNCES for this article.

This article previously appeared on the GLP Jul 22, 2013.

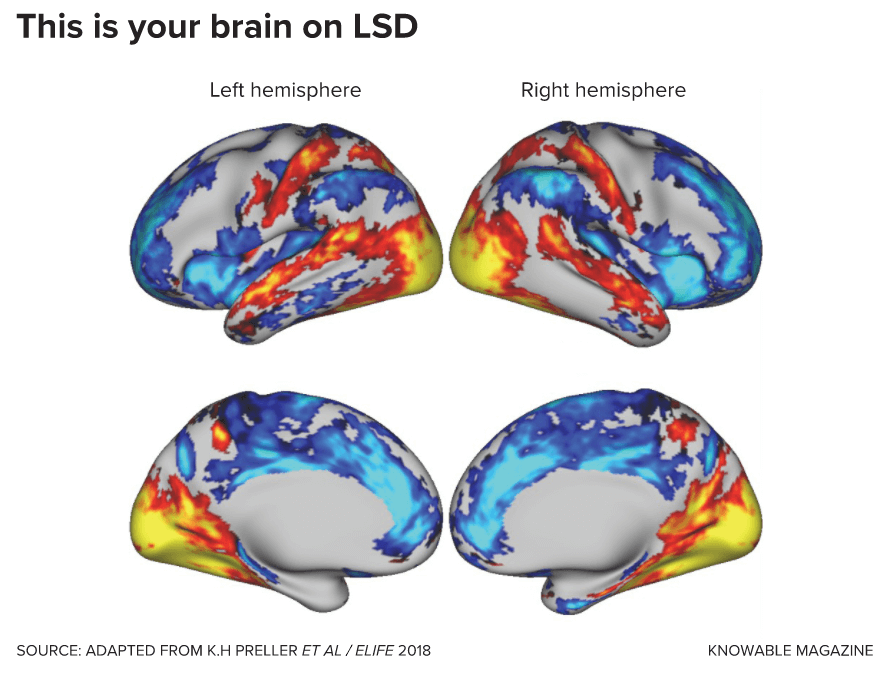

Or what seemed like hours to Seth. A researcher at the UK’s University of Sussex, he studies how the brain helps us perceive the world within and without, and is intrigued by what psychedelics such as LSD can tell us about how the brain creates these perceptions. So a few years ago, he decided to try some, in controlled doses and with trusted people by his side. He had a notebook to keep track of his experiences. “I didn’t write very much in the notebook,” he says, laughing.

Or what seemed like hours to Seth. A researcher at the UK’s University of Sussex, he studies how the brain helps us perceive the world within and without, and is intrigued by what psychedelics such as LSD can tell us about how the brain creates these perceptions. So a few years ago, he decided to try some, in controlled doses and with trusted people by his side. He had a notebook to keep track of his experiences. “I didn’t write very much in the notebook,” he says, laughing.