For most of us, the inner workings of our cells are at best abstract. That changed in 2006 with a short video — no longer than some commercials — called “The Inner Life of the Cell.” Now the folks behind this movie have released a new video that offers insight into how our cells seem to work “in spite of themselves.”

First, “The Inner Life of the Cell”:

If it seems familiar, that’s probably because it’s become a staple across the web and at educational facilities. Carl Zimmer, writing for the New York Times, walks us through what happens in the video:

[An immune cell] rolls along the interior wall of a blood vessel until it detects signs of inflammation from a nearby infection.We dive into the cell to see what happens next. Molecules swim through the cell like dolphins, relaying the signal from the outside. Certain genes switch on, and the cell makes new proteins that are put into a blob called a vesicle. An oxlike protein called kinesin hauls the vesicle across the cell, walking along a molecular cable.

Once the vesicle reaches its destination, it releases its cargo. The new proteins cause the immune cell to stop rolling, and it flattens out and slips between the cells that make up the blood vessel wall so that it can seek out the infection.

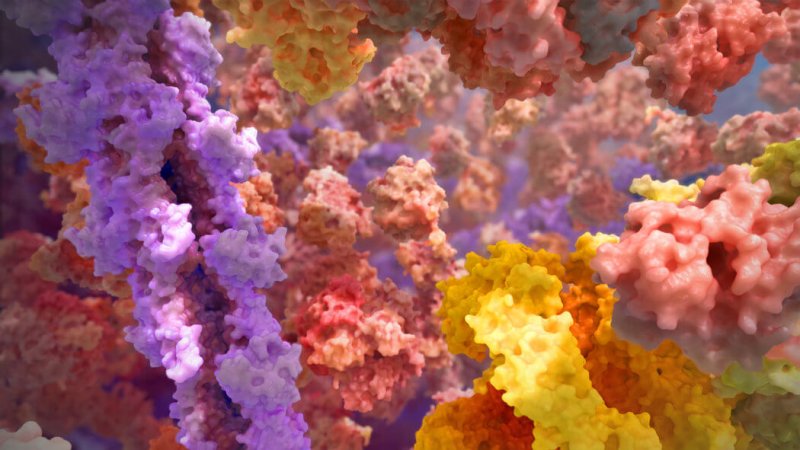

All of this happens in such a wondrous, ordered fashion that it seems like our cellular machinery would make Henry Ford jealous. Problem is, notes Zimmer, the workings of our cells aren’t nearly so streamlined. Rather, they’re overstuffed with proteins. And they don’t move with “stately grace” like those in the 2006 video, they’re constantly jostling up against water molecules, cell membranes, and other proteins. Add to this the incredible three-dimension complexity of proteins, and you’ve got quite a computing challenge if you want to create a more accurate simulation.

The folks behind the first animation, BioVisions at Harvard and Xvivo in Connecticut, spent the last two years on a quest to give us a more accurate look at the inside workings of a cell. Watch the video — and read Zimmer’s summary — below.

In this movie, we enter a neuron by diving through a channel on its surface. Once inside, we’re instantly surrounded by a swarm of molecules. We push through the crowd until we reach a proteasome, a barrel-shaped molecule that shreds damaged proteins so their components can be used to make new proteins.

Once more we see a vesicle being hauled by kinesin. But in this version, the kinesin doesn’t look like a molecule out for a stroll. Its movements are barely constrained randomness.

Every now and then, a tiny molecule loaded with fuel binds to one of the kinesin “feet.” It delivers a jolt of energy, causing that foot to leap off the molecular cable and flail wildly, pulling hard on the foot that’s still anchored. Eventually, the gyrating foot stumbles into contact again with the cable, locking on once more — and advancing the vesicle a tiny step forward.

Your cells don’t work in a perfectly choreographed dance. The “barely contained randomness” on display in the new video, notes Zimmer, helps us understand how disease like Parkinson’s work. They’re caused when defective proteins clump together, essentially gumming up the works inside of cells.

The other thing that is striking about the new video — and Zimmer touches on this — is how it emphasizes the importance of three-dimensional shapes to how cells work. The structure of proteins is vital to how they do their work, with the varying shapes and structures letting them attach to different points or form a cage around other molecules that need to be transported. In the abstract, all these cellular structures — proteins, DNA, ribosomes, what have you — tend to become vague spheroids shapes. The reality couldn’t be more different.

Read Carl Zimmer’s article at the New York Times: “Watch Proteins Do the Jitterbug“

Kenrick Vezina is Gene-ius Editor for the Genetic Literacy Project and a freelance science writer, educator, and naturalist based in the Greater Boston area.

Additional Resources:

- “Scicurious Guest Writer! Ribosomes: ‘Prepare to be translated’” Abid Javed | Scientific American

- “Can an artificial protein defeat infection by supercharging immunity?” Melissa Healy | Los Angeles Times

- “Seeing X Chromosomes in a New Light,” Carl Zimmer | New York Times