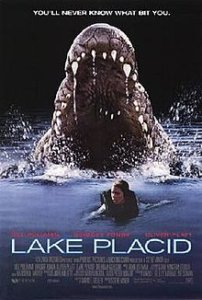

The use of CRISPR to edit genes is perhaps the only novel plot point in this latest monster movie. An evil head of a biotech company subverts a scientist’s work to fashion a bioweapon that revs up the growth hormone gene, and more, in three unfortunate animals. Cue Godzilla, King Kong, and the beast in Lake Placid.

But the screenwriters seem to confuse gene editing with an infectious bioweapon, like anthrax. The tagline at IMDb reveals the befuddlement: “When three different animals become infected with a dangerous pathogen, a primatologist and a geneticist team up to stop them from destroying Chicago.” Infectious disease, genetic modification, or both?

CRISPR canisters from space

CRISPR canisters from space

The first frame in the film is just wrong: a written statement that CRISPR was invented in 1993. Nope.

The gene editing technology began as a conversation between two women at a conference in 2011, which they told me about here. Their initial CRISPR paper is from 2012, and they’ll likely share a Nobel prize with Feng Zhang, who also pioneered the technology. And two other genetic editing technologies preceded CRISPR, zinc fingers and TALENs, by just a few years. Perhaps the film is referring to homologous recombination, which is the mechanism, not the name, and dates to the late 1980s.

We also learn right away that in 2016 CRISPR was declared a “weapon of mass destruction and proliferation” in the US. Good to know.

In the opening scene, a distraught astronaut aboard Athena 1 frantically searches for a rat. The crew is dead and blobs of blood drift by. “A beast!” she yells as a giant rodent lurches. She grabs a bunch of black canisters before ejecting herself in a pod. But the pod soon blows up, showering the mysterious canisters into the earth’s atmosphere, unknowingly seeding the planet with a “pathogen.” We never learn what the pathogen is (bacterium? virus? ameba?), nor why it was being nurtured in space.

Oopsies!

Scene change. Hunky San Diego Wildlife Sanctuary and primatologist Davis Okoye (Dwayne “the Rock” Johnson) is showing a young nerd, frat boy, and blonde how to acclimate a new gorilla into the group. Soon, albino George the ape ambles out and he and Davis chatter in sign language. George is particularly adept at flashing a third finger, in context. He’s smart! But the albinism, a single gene trait, is never addressed, and since its rarity makes George valuable, it makes no sense that the poachers slaughter his family, which we see in grizzly flashback.

Scene change. Hunky San Diego Wildlife Sanctuary and primatologist Davis Okoye (Dwayne “the Rock” Johnson) is showing a young nerd, frat boy, and blonde how to acclimate a new gorilla into the group. Soon, albino George the ape ambles out and he and Davis chatter in sign language. George is particularly adept at flashing a third finger, in context. He’s smart! But the albinism, a single gene trait, is never addressed, and since its rarity makes George valuable, it makes no sense that the poachers slaughter his family, which we see in grizzly flashback.

That night the space crap lands, flung from meteors (Pitbull’s “Fireball” would have fit well here). A celestial canister plops down in the gorilla compound in San Diego, and curious George picks it up, opens it, and white powder disperses in his face, with nary a singe from the sizzling metal. Another canister lands in southern Wyoming, “infecting” a wolf. A third lands in Everglades National Park, similarly anointing a crocodile.

Gorilla, wolf, crocodile. Remember them, the cast of gene-edited vertebrate characters.

Size matters, and more

The next morning, George has escaped his compound and killed a bear, sustaining some cuts. He’s curled up in a cave and crying, signing, like a Trump tweet, “Sad.” Hurt. Bear. Upset.

George is bigger! Overnight!

Scene change: to biotech firm Energyne in a Chicago skyscraper, to squabbling siblings Claire Wyden, who looks like a clone of Today Show host Savannah Guthrie, and her whining brother, Brett. The company funded the research to create the pathogen in the canisters, building of the spaceship, and a private military operation in Greeley, Ohio.

News on a screen in the background shows five dead guys and a giant wolf pawprint. “It’s infected by the pathogen,” Claire mumbles mysteriously.

Another scene change. Kate Caldwell (Naomie Harris) is in her LA apartment. Next to her Starbucks detritus are a few genetics textbooks. Odd, because scientists don’t need textbooks, students do. We learn later that Kate indeed has a PhD in biochemistry, a degree in conservation genetics, and vaguely used CRISPR on endangered species in the Arctic.

So what, exactly, is CRISPR? A biotechnology that isn’t as gee-whiz as it seems. It’s a molecular toolbox that consists of a “guide” RNA to direct cutting of a selected DNA sequence by an enzyme that’s also part of the package. Then the cell’s natural DNA repair system fixes the damage. To get these components inside cells, researchers use the viruses already used for years in gene therapy (retro-, adeno-associated-, adeno, and lenti viruses) and, more recently, injection or lipid nanoparticles, to avoid an immune response to viruses.

Early reviews

The first reviews, from journalists invited to the premier, seemed to not quite get the science, but that’s understandable because it is so fragmented.

Stat News gushed over The Rock, then talked about CRISPR “rewriting the code of life,” the common error in terminology that makes me, as a genetics textbook author, want to scream. If the genetic code wasn’t universal – all species use the same DNA triplets to specify the same amino acids – technologies that sometimes mix gene parts from different species, even just in the promoter regions of genes that control expression, wouldn’t work. Anyone take insulin produced in bacteria or yeast? And this film review is full of genetic code mistakes. They all mean “DNA sequence,” not “genetic code.” The code is the correspondence. I’m sure Dr. Kate’s textbooks have the requisite genetic code chart of RNA codon-amino acid assignments that also festoons my office wall.

Interestingly, the Daily Bruin used “mutagen,” which at first confused me because classically mutagens have been just nasty chemicals and radiation. That’s what I used to make flies with legs on their heads for my PhD research. But the biotechnologies that replace DNA sequences, like CRISPR, also alter the DNA. So OK.

Genetic changes

Meanwhile, the ever-enlarging George is caged in a lab for tests. Davis glances down at the results. “That can’t be right! His neuromuscular synapses are increasing! His blood has lethal levels of growth hormone!”

A surly George soon bursts out of the cage. Davis wants to save him, but what’s wrong? The brilliant Kate knows. “He’s growing, isn’t he? And has speed and agility. He’s demonstrating levels of aggression you don’t see in his species.” The ape has grown from 7 feet tall, 500 pounds, to 9 feet tall and 1000 pounds, in one day.

From George’s phenotype, I suspect that Claire had her minions weaponize CRISPR to replace:

- controls for the growth hormone gene from a different species – the coding portion is similar among vertebrates – upping it’s expression

- the monoamine oxidase A gene with a variant associated with violence and aggression

- the prestin gene with the bat version that imparts echolocation (clever!)

The storyline obeys Isaac Asimov‘s basic law of science fiction: Change. One. Thing. And Rampage does that – not CRISPR, that’s just a means to an end, but the acceleration. The GMO-fast-growing salmon that might have inspired the plot attain adult size twice as fast – in 18 months, not overnight – but don’t exceed normal body size. No one’s seen a GMO salmon the size of Moby Dick.

Kate’s explanation of CRISPR is a swipe across her iPhone to show Davis cute animal pix. No guide RNAs, no DNA-cutting enzymes, no DNA repair. Still, with George bellowing and rattling his cage in the background, she explains that CRISPR is usually limited to fixing one cell at a time (no), but she’s found a way to change all an organism’s cells at once, “every DNA strand.” No again. Insertion sites are chosen, the guide RNA and enzyme not released willy-nilly all over a genome, triggering the dreaded off-target effects. Maybe Kate needs that textbook after all.

In fact the geneticist could have said “abracadabra” instead of CRISPR the whole time and the story would not have changed.

Just as I was getting irked at the missed opportunity to mention what CRISPR can do, such as possibly treat Huntington’s disease, Kate explains that she developed her strategy to save her brother, who was dying of an unnamed condition. She was fired from Energyne 2 years ago and stole stuff.

End of science. Just fire and chases

George busts out of captivity, and the rest of the film is chase scenes involving the gargantuan gorilla, wolf (which can fly, love those genetic modifications), and crocodile as they converge on the Windy City.

The action accelerates.

A military contractor is unaware of the giant wolf sneaking up from behind, conjuring the clueless lawyer on the crapper in Jurassic Park eaten by a T. rex. Crunch! There goes GI Joe’s head!

A military contractor is unaware of the giant wolf sneaking up from behind, conjuring the clueless lawyer on the crapper in Jurassic Park eaten by a T. rex. Crunch! There goes GI Joe’s head!

Mysterious government guy Harvey Russell introduces himself to Davis and Kate: “When a scientist shits in the bed, I’m the guy they call to change the sheets.”

Then somehow George is back, and his cuts have healed! “The DNA makes it capable of extreme regeneration” says the ever-helpful geneticist.

“How will we cure George?” laments Davis, as the music soars.

An antidote, of course! One tiny dose of R-19, Claire the biotech bitch smirks, and the behemoths will follow the low frequency radiowaves emanating from the tower housing Energyne, thanks to their CRISPR-ed in batbiosonar DNA.

Watching a newsfeed of the rampage, Claire declares, “The pathogen is doing what we designed it to.” Well, no. “The pathogen,” whatever it is, isn’t the bioweapon, it’s the delivery system for the CRISPR components, like a rubber band in a slingshot.

The crocodile that nobody knew about suddenly ripples from beneath a tourboat on Lake Michigan, then surges up to swallow a plane. Someone is bellowing “EKIA,” and I wonder if perhaps the beasts are planning a side trip to Ikea, but they head for company headquarters.

The crocodile that nobody knew about suddenly ripples from beneath a tourboat on Lake Michigan, then surges up to swallow a plane. Someone is bellowing “EKIA,” and I wonder if perhaps the beasts are planning a side trip to Ikea, but they head for company headquarters.

Fire! Explosions! People flee, vehicles crash, monsters invade upper stories, and one great swallow even beats the genetically-enhanced shark ingesting Samuel L. Jackson in 1999’s Deep Blue Sea.

“We can’t stop them! We gotta get that antidote!” hollers Davis.

The human characters collide on the 85th floor of the skyscraper, and Kate the geneticist filches a test tube of antidote from a cryopreservation tank, hopefully not the type used in the recent fertility clinic meltdowns. Everyone races to the roof, where Kate somehow slips the antidote to George the giant ape. This happens too fast to grasp. Perhaps she gives it to him in a latte.

Thirty more minutes of gore and fire follow, but I won’t give away the touching ending.

Thirty more minutes of gore and fire follow, but I won’t give away the touching ending.

Context

My mentor in grad school called the fear of an escaped genetically-altered organism the “triple-headed purple monster” mindset. This was back when the fledgling biotech industry policed itself by developing the measures of physical and biological containment still in place for technologies that combine DNA from different species.

The film might have worked better back then, when the fears were new and more grounded, with biotech-based drugs and the genetically-modified foods we’ve been eating for years still to come. Although great fun to watch, Rampage lacks the sophistication, continuity, and intelligence of the Jurassic Park franchise. (But Rampage at least doesn’t make the genetic code error, as Jurassic Park does with its “billions of genetic codes.”)

So, after all that, what does Rampage have to do with CRISPR gene editing? Absolutely nothing! I hope I’m invited to the premier of the next biotech film.

Ricki Lewis is the GLP’s senior contributing writer focusing on gene therapy and gene editing. She has a PhD in genetics and is a genetic counselor, science writer and author of The Forever Fix: Gene Therapy and the Boy Who Saved It, the only popular book about gene therapy. BIO. Follow her at her website or Twitter @rickilewis.