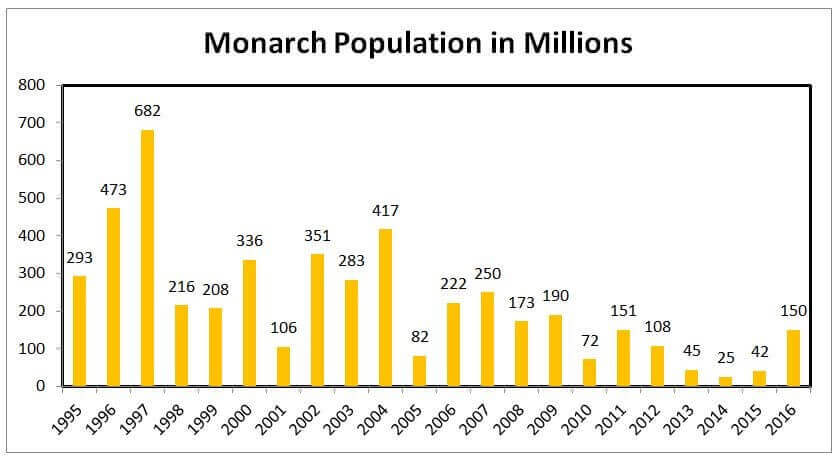

The plight of the Monarch has been well documented in recent years, with the population of the migratory creature plunging dramatically. The Monarch suffered an 88 percent decline in North America from 1999 through 2012, but its numbers have rebounded since, although they are still down considerably over the past 20 years.

According to the independent Illinois Butterfly Monitoring Network, the population in 2018 reached the highest levels of the past 25 years, and the fourth highest level since 1993. The number of butterflies heading south to Mexico may reach as many as 250 million over the 2018-19 winter. At its peak in the 1990s, the population reached an estimated 900 million.

The decline has been accompanied by dire predictions about the future of these insects by some scientists. According to the anti-GMO advocacy group the Center for Biological Diversity (CBD), which dismisses the recent multi-year rebound as anomalous, claims:

A 2016 study by the U.S. Geological Survey concluded that due to ongoing low population levels, there is between an 11 percent and 57 percent risk that the eastern monarch migration could collapse within the next 20 years. Scientists estimate the monarch population needs to reach 225 million butterflies to be out of the danger zone.

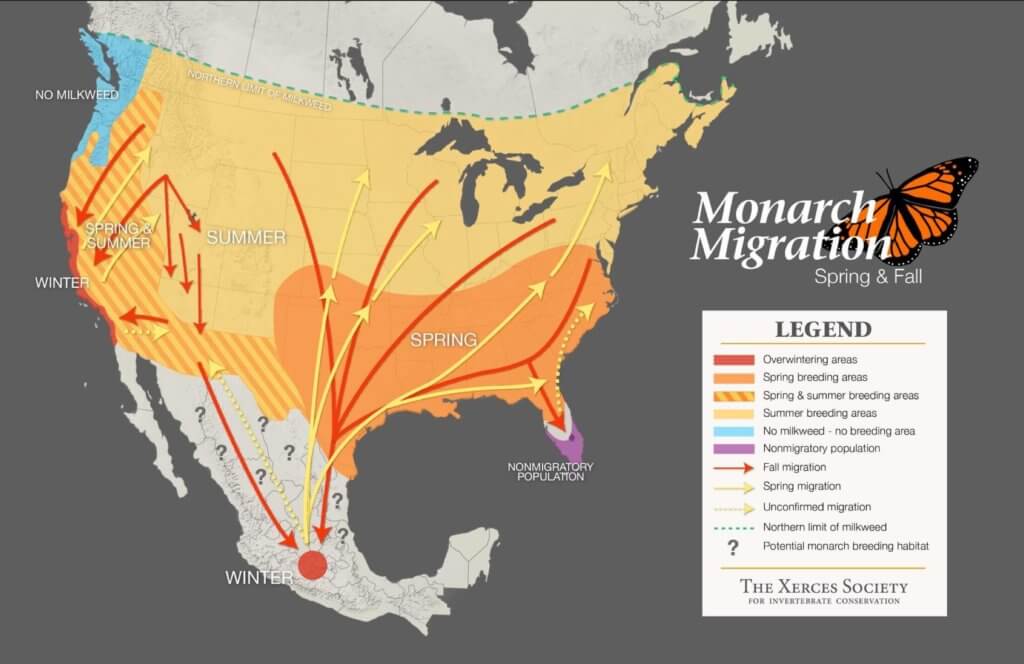

Before exploring the reasons for population reduction, consider the life of the insect. Each year, the Monarch makes a 6,000-mile round-trip journey that spans multiple generations. They mate in Mexico in the spring, before traveling to northern Mexico and some places in the very southern US, where they lay eggs on milkweed plants. The parents die there, but their caterpillar offspring feed on the milkweed, before traveling north to Canada, where another generation is born. These unmated butterflies then return to Mexico for overwintering, eating nectar, rather than milkweed, along the way.

The piece of this migratory pattern that’s received the most attention is the role of milkweed. Although a serious problem for farmers, it is a key food source for butterflies, which have developed a resistance to its poison. Large swaths of the weed have been eliminated by farmers using the herbicide glyphosate and more recently dicamba. Some researchers have connected the loss of milkweed and declining butterfly populations, prompting widespread media coverage, with stories like this one in Slate:

Karen Oberhauser, a conservation biologist at the University of Minnesota, and a colleague estimated that as Monsanto’s Roundup Ready corn and soybeans spread across the Midwest, the amount of milkweed in farm fields fell by more than 80 percent. Oberhauser determined that the loss of milkweed almost exactly mirrored the decline in monarch egg production.

“We have this smoking gun,” Oberhauser said. “This is the only thing that we’ve actually been able to correlate with decreasing monarch numbers.”

Anti-GMO activists have seized upon the narrative, arguing that the Monarch’s problems are one more reason why GMOs (and associated herbicides) should be feared.

The activist Center for Food Safety issued a dire report on the Monarch in 2015:

Glyphosate is one of the very few herbicides that kills common milkweed and is particularly effective when sprayed later in the season on Roundup Ready corn and soybeans.

The devastation extends beyond milkweed. Flowering plants that provide Monarch adults with nectar are also under siege from increasing herbicide use and drift. Next-generation genetically engineered crops resistant to volatile herbicides as well as glyphosate will dramatically exacerbate these impacts. Because most wildflower habitat is found near corn and soybean fields in the Midwest, increased herbicide use and drift will reduce nectar resources that monarch adults require for breeding and for their epic migration.

More recently, attention has focused on the increased use of the herbicide dicamba, which is paired with a new line of soybeans developed by Monsanto designed to work in tandem with the older herbicide. Use of dicamba has proven problematic across the country, with complaints about unexpected crop damage caused by herbicide drift with some links made to Monarch declines. A 2018 report by St. Louis Public Radio included comments from Nathan Donley, senior scientist at the CBD:

With most pesticides, the damage is delayed and it’s harder for people to make the connection between pesticide use and harm,” Donley said. “But with dicamba, you can actually see the damage in real time. I hope this is a wake-up call to the EPA and the farming community.

Most scientists, however, suggest there is far more at play in the Monarch’s decline than a patchwork loss of milkweed. A respected research team headed by Anurag Agrawal at Cornell University, author of a well-received best-selling 2017 book, Monarchs and Milkweed: A Migrating Butterfly, a Poisonous Plant and the Remarkable Story of Their Coevolution, addressed the milkweed-herbicide connection in a 2016 study, examining 6,000 migratory reports by butterfly watchers between 1993 and 2014.

The researchers concluded that the most substantial population decline is occurring during winter in Mexico, where the use of glyphosate is not a factor:

The monarch butterfly is far from being threatened, but the eastern USA migration, one of the most spectacular animal migrations in the world, may be an endangered phenomenon. To identify and manage the risk factors associated with its decline, deeper critical analyses of the existing data are essential. We do not dispute that milkweed is essential for larval monarchs, and might serve as a buffer against further aggravation. Yet our analyses indicate that other stages are critical, so milkweed conservation alone is unlikely to be sufficient to preserve the migration. Additional resources are necessary to study and improve the transition between summer breeding in the USA and overwintering in their highland forested habitats in Mexico.

“The consistent decline at the overwintering sites in Mexico is cause for concern. Nonetheless, the population is six times what it was two years ago, when it was at its all-time low,” Agrawal has said. He credits the population rebound to improved weather and release from the severe drought in Texas.

The latest research directly contradicts an alarming set of graphics posted by CBD showing “correlation between glyphosate use and monarch migration routes and breeding.”

In fact, there is almost no Monarch breeding going on in the United States and Canada close to areas where they lay their eggs. The decline in Monarchs happens in two places where glyphosate is not an issue: in overwintering grounds in Mexico (where it’s not used) and as their adult forms fly back to Mexico (when they no longer feed on milkweed, instead preferring nectar). Monarchs fly over areas where glyphosate (and other herbicides) are used on corn and soybeans. But if Monarch caterpillars aren’t raised in those areas, then banning these herbicides or dramatically increasing the milkweed populations of the entire Midwest, from Oklahoma to Saskatchewan, won’t help the butterfly.

A 2019 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) provided further evidence that GMO crops and herbicides often paired with them are not driving the decline in Monarch butterflies. The researchers used digitized records from museums and herbaria around the US to track changes in Monarch populations and milkweed between 1900 and 2016. They blamed the bulk of the deaths on mortality caused during the butterflies’ long annual winter journey to Mexico, a theory known as the “migration mortality hypothesis,” which has emerged as the consensus among scientists. But they stressed the problems are multi-factorial.

“They’ve been dying off since the middle of the 20th century, long before genetically modified crops,” said co-author Josh Puzey, Assistant Professor of Biology at William & Mary University. GMO crops paired with glyphosate were introduced in North America in 1996. “We tested the role of farm size, herbicide use and fertilizer use. Collectively, the model explained less than 20 percent of the variation in milkweed abundance. In other words, there’s a lot of variation in milkweed abundance that’s not explained by farm size, herbicide use or fertilizer use.”

The study authors said more work needed to be done to explain the 80 percent of the decline they couldn’t account for, and concluded with a word of caution as researchers continue to investigate:

Whatever factors caused milkweed and monarch declines prior to the introduction of GM crops may still be at play, and, hence, laying the blame so heavily on GM crops is neither parsimonious nor well supported by data.

A 2020 study using data compiled by the conservation group Monarch Watch challenged the consensus that the decline since the 1990s was linked to mortality during migrations. The main determinant of yearly variation in overwintering population size, the researchers found, is the size of the summer population. These findings support the alternative conclusion that sustaining the Monarch migration will require the restoration of over a billion milkweed stems in the Upper Midwest in the coming years.

The National Wildlife Federation, which is not an ideological advocacy group, has offered this perspective:

Monarchs also have been hit hard in recent years by extreme weather events such as droughts, storms, heat waves and unusually cold or wet springs that delay reproduction events likely to become more frequent with climate change. Some studies suggest that by the end of this century, global warming may eliminate forests within the insects’ Mexican reserves. Even without such losses, overwintering butterflies are constantly at risk from bad weather. A single storm in 2002 killed an estimated 500 million monarchs eight times more butterflies than survive in North America today.