Among the more popular criticisms aimed at Monsanto is this idea that the company is in the midst of a legal rampage against farmers whose fields contain trace amounts of unlicensed GMO crops. If true, it would be a legitimate fear, considering how easy it is for seeds to migrate (via wind, birds, etc.) from one field to another.

The genesis of these claims are traced to an August 1998 Monsanto suit against Percy Schmeiser, a canola grower in Canada. It was a case that helped define the legal rights of companies and their seeds.

But the case, and misrepresentations of it, gave birth to the anti-GMO narrative suggesting that Monsanto routinely sues farmers whose fields have been accidentally contaminated with patented seeds. The view was solidified in the 2009 documentary about the case, David versus Monsanto.

The affair started in 1997, when Schmeiser was spraying the herbicide Roundup (glyphosate in generic form) around power poles on the edge of his property. He noticed that some of the canola plants weren’t killed by the spray, revealing that they were GMO plants. It’s unclear how they got there it’s possible they came from neighboring farms or from grain trucks passing on the road.

The affair started in 1997, when Schmeiser was spraying the herbicide Roundup (glyphosate in generic form) around power poles on the edge of his property. He noticed that some of the canola plants weren’t killed by the spray, revealing that they were GMO plants. It’s unclear how they got there it’s possible they came from neighboring farms or from grain trucks passing on the road.

Regardless, Schmeiser sprayed more Roundup in several surrounding acres, isolating a small section of GMO canola. The farmer then saved the seeds from the GMO canola and replanted them in 1998.

It should be noted that by the time his case went to trial, there was no dispute over the accidental contamination. The case revolved around Schmeiser’s decision to harvest, save and replant the GMO canola. It’s a critical distinction, considering that Schmeiser often is portrayed as an accidental victim. Postdoctoral fellow Wen Zhou wrote about the case for Harvard University’s Science in the News:

There is a popular misconception that Monsanto sued farmers for selling its proprietary crops, even though those innocent farmers unknowingly harvested their Roundup-contaminated land. According to the Supreme Court record, however, that was not the case. Percy Schmeiser, the main character in David versus Monsanto, went to great lengths to enrich the Roundup Ready canola plants that originated from his neighbor’s land: by treating his crops with Roundup, he ensured that only the resistant strains persisted. In the following seasons, he replanted the seeds without having a licensing agreement with Monsanto. The unusually high prevalence (95-98%) of tolerant plants in Schmeiser’s fields clearly demonstrated infringement in the eyes of the court, and Monsanto claimed rightful remedy for its loss of profit.

In the end, the Canadian courts found in favor of Monsanto, ruling that no matter how a patented seed finds its way into a field, that seed is still owned by the company that made it. (Schmeiser testified during trial about his scheme for identifying and hoarding herbicide-resistant seeds that he used for the illegal planting.) But the court rejected Monsanto’s claim of damages, saying Schmeiser did not actually benefit from the planting of Roundup Ready canola because he never sprayed the harvest with the glyphosate herbicide, so he gained no economic benefits from his illegal activity.

The ruling prompted criticism from anti-GMO groups, who argued that it put too much burden on farmers to control what grows in their fields. It is far too easy, they said, for wind and other factors to carry unwanted seeds into fields where they don’t belong. Pat Venditti, a genetic engineering campaigner for Greenpeace Canada said:

“Monsanto has introduced an uncontrollable crop with no liability to farmers or the public. This ignores the widespread contamination being caused by Monsanto. The decision of the court essentially makes farmers liable to Monsanto for Monsanto’s own genetic pollution. It means that Monsanto can reach into farmers’ fields and steal their profits and livelihoods.”

In the Schmeiser case, of course, such a claim is disingenuous, as more than 90 percent of his acreage was from Roundup-tolerant canola.

The Schmeiser case dealt with farmers who plant patented seeds without ever paying a licensing fee. But what about a farmer who pays the fee, and then wants to save seeds from his crop for future use?

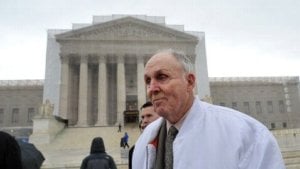

That issue was settled in a landmark 2013 case involving an Indiana farmer, Vernon Bowman, who attempted to get around Monsanto’s soybean patent, using what he saw as a loophole in the law. When farmers buy seeds from Monsanto or any of its competitors they sign a contract that, among other things, prevents them from saving or re-using seeds. (Examples can be found here and here.)

Bowman bought Monsanto seeds for his main crop. But he also purchased soybeans being sold as animal feed at a local grain elevator. He planted them and sprayed them with Roundup, figuring there would be enough Roundup-Ready beans in the lot to make it worthwhile. He used seeds from the surviving plants for his second, late-season, planting.

When Monsanto discovered his tactics and sued, Bowman tried to argue patent exhaustion claiming that Monsanto’s rights extended only to the first generation of seeds.

His defense was rejected unanimously by the US Surpreme Court (here), with Justice Elena Kagan writing:

Under the patent exhaustion doctrine, Bowman could resell the patented soybeans he purchased from the grain elevator; so too he could consume the beans himself or feed them to his animals. But the exhaustion doctrine does not enable Bowman to make additional patented soybeans without Monsanto’s permission.

That ruling serves as the basis for companies like Monsanto to protect the value of the seeds developed through their research arms. And while the verdict was expected by many legal observers, it did offer clarification for farmers (including organic farmers) and their relationships with the vast majority of hybrid and GMO seed sellers, wrote Ohio State law professor Peggy Kirk Hall:

The Monsanto ruling is not a big surprise but it does send a strong message to farmers, some of whom have likely grumbled over seed patents and limitations on the age-old practice of saving seed. With the Supreme Court’s decision, it’s clear that the current legal system simply won’t tolerate replantings of patented seeds. Instead, the law will support continued efforts by patent holders to monitor what farmers do with patented seed. Replanting of patented seed, whether intentional or accidental, is more than ever a high risk activity.

The ruling was criticized by anti-GMO groups, who argued that it deprived farmers of the ability to save seeds for future plantings. Henry Rowlands, director of anti-GMO website Sustainable Pulse, wrote:

The fact that the US Supreme Court has supported Monsanto’s attempt to take over the world’s food system is a complete disgrace.

What about cases in which farmers inadvertently plant GMO seeds clearly not the situation with Schmeiser and Bowman. That issue arose in 2011, when Monsanto was sued by the Organic Seed Growers and Trade Association. The plaintiffs included 83 farmers, seed companies, agriculture organizations and public interest groups.

They sought a declaratory judgment that would prohibit Monsanto from suing farmers in the future over cases of inadvertent GMO contamination. Their argument was hurt, however, when they couldn’t produce even one case in which a farmer had been sued for accidental contamination.

They sought a declaratory judgment that would prohibit Monsanto from suing farmers in the future over cases of inadvertent GMO contamination. Their argument was hurt, however, when they couldn’t produce even one case in which a farmer had been sued for accidental contamination.

The battle came to an end in January 2014, when the U.S. Supreme Court agreed with a lower court ruling that said there was no reason to issue such a judgment, since the company has pledged, on its website, to not sue farmers whose crops are accidentally contaminated, which has been its long-time position. By doing so, the company effectively bound its own hands in this regard:

Monsanto’s binding representations remove any risk of suit against the appellants as users or sellers of trace amounts (less than one percent) of modified seed.”

The ruling was criticized by the organic trade group:

The Supreme Court failed to grasp the extreme predicament family farmers find themselves in. The Court of Appeals agreed our case had merit. However, the safeguards they ordered are insufficient to protect our farms and our families. This high court which gave corporations the ability to patent life forms in 1980, and under Citizens United in 2010 gave corporations the power to buy their way to election victories, has now in 2014 denied farmers the basic right of protecting themselves from the notorious patent bully Monsanto.